I think Number Talks are such a powerful routine in developing students’ fluency and flexibility with operations, but maybe not for the reason most think. One of the most highlighted purposes of a Number Talk is the ability to elicit multiple strategies for the same problem, however, an even more important goal for me during a Number Talk is for students to think about the numbers they are working with before they begin solving. And then, as they go through their solution path, think about what numbers are helpful in that process and why.

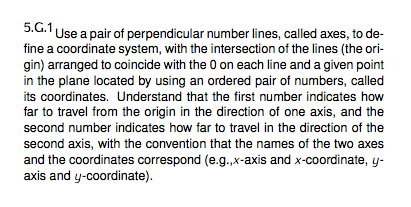

The struggle with trying to dig deeper into that thinking is simply, time. If the opportunity arises, I ask students about their number choices during the Talk but often students just end up re-explaining their entire strategy without really touching on number choices. Not to mention the other 20ish students start losing interest if they take too long. I do think it is a particularly tough question if students are not used to thinking about it and when the thinking happens so quickly in their head, they don’t realize why they made particular choices.

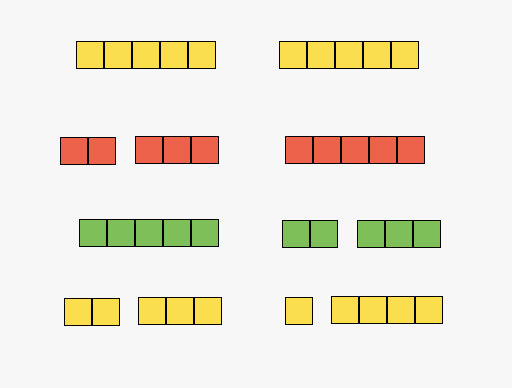

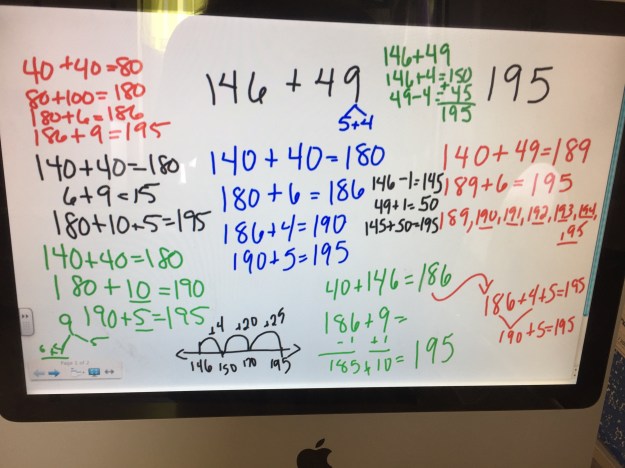

Last week in 2nd grade I did a Number Talk with two problems, one addition and one subtraction. During the addition talk, I noticed students using a lot of great decomposition to make friendly numbers (the term they use to describe 10’s and 100’s).

During the subtraction problem, I saw the same use of friendly numbers, however in this one I actually got 100 as an answer. My assumption was because the student knew he was using 100 instead of 98, but got stuck there so went with 100 as the answer. I was really impressed to see so many strategies for this problem since subtraction is usually the operation teachers and I talk endlessly about in terms of where students struggle. I find myself blogging on and on about subtraction all of the time!

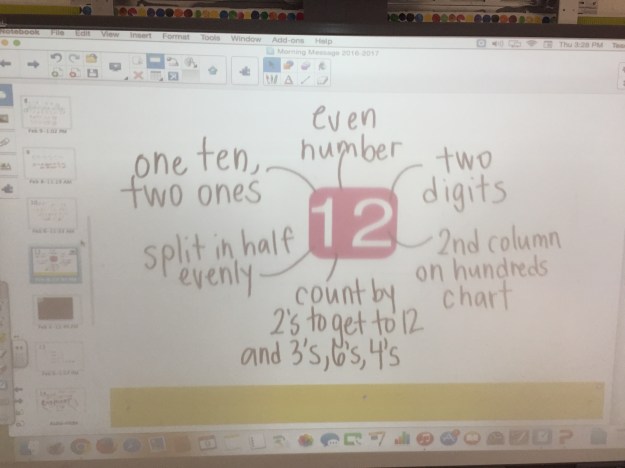

When the Number Talk ended, I looked at the board and thought if my goal was to elicit a lot of strategies, then I was done – goal met. However, I chose the numbers in each problem for a particular reason and wanted students to dig more into their number choices.

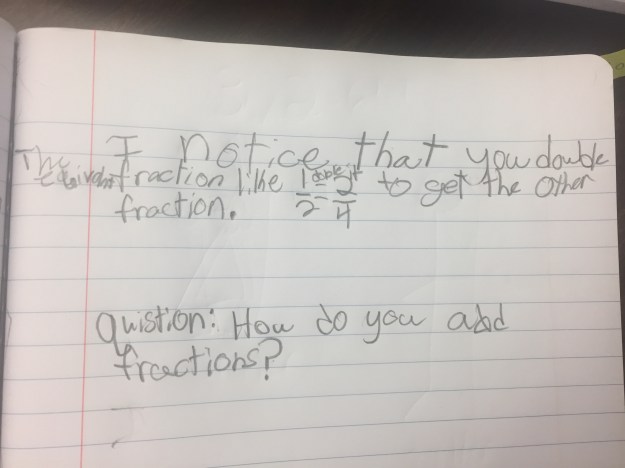

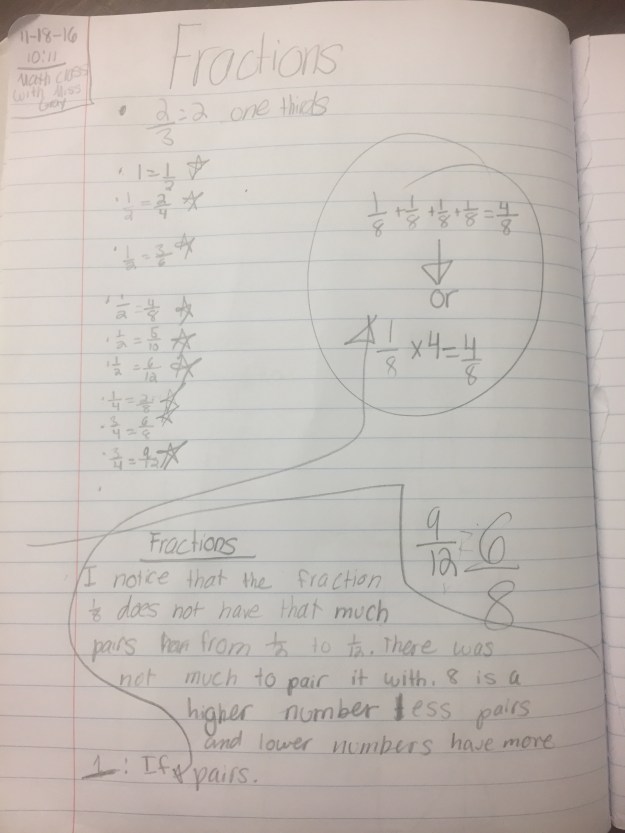

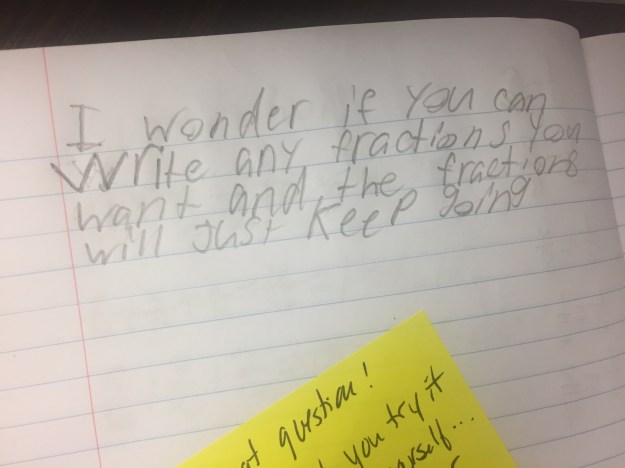

This is where I find math journals to be so amazing. They allow me to continue the conversation with students even after the Number Talk is finished.

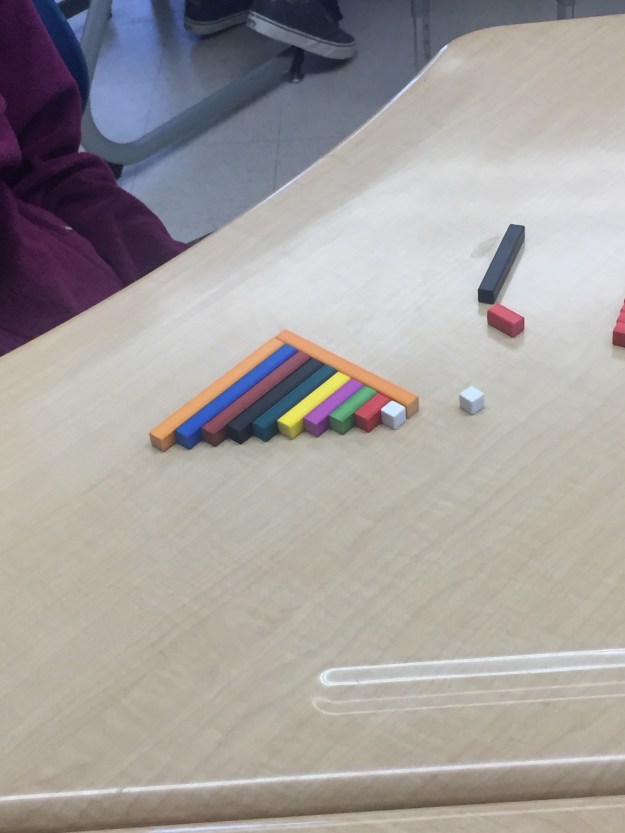

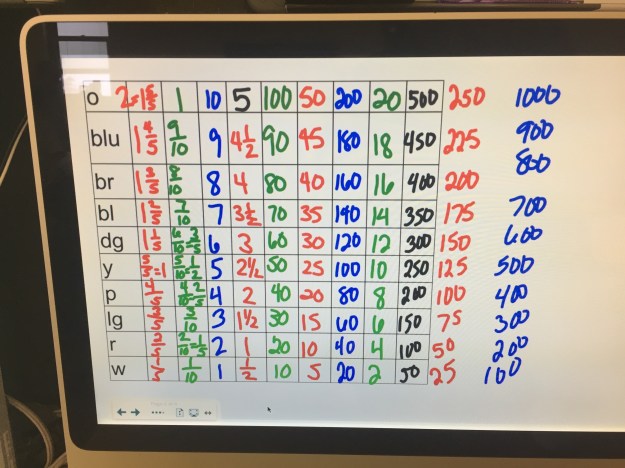

I went back to the 100, circled it and told the class that I noticed this number came up a lot in both of our problems today. I asked them to think about why and then go back to their journal to write some other problems where 100 would be helpful.

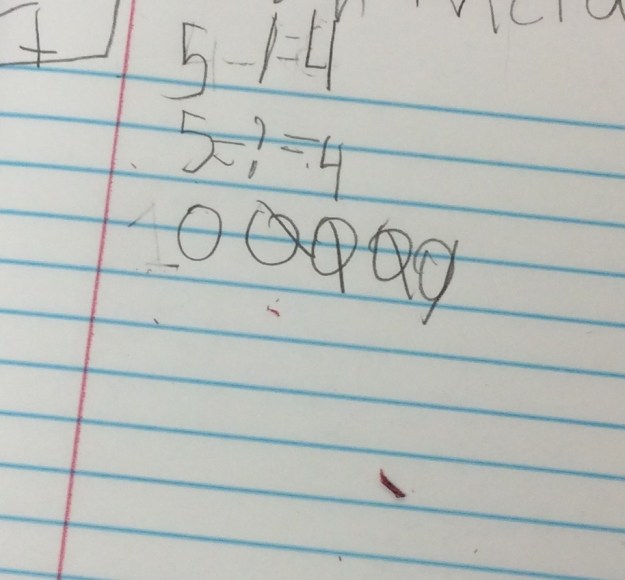

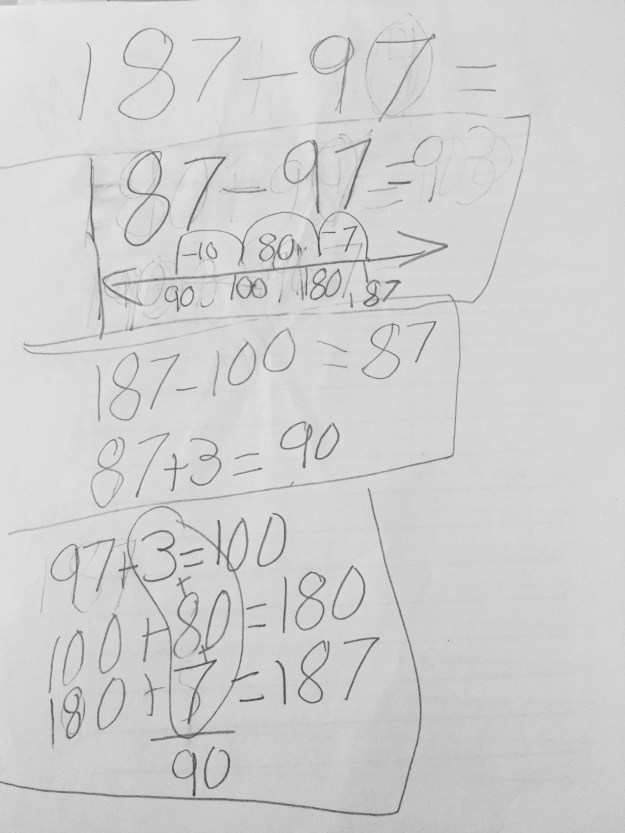

Some used 100 as a number they were trying to get to, like in this example below. I really liked the number line and the equations that both show getting to the 100, but in two different ways.

This student got to 100 in two different ways also. I thought this was such a clear explanation of how he decomposed the numbers to also use 10’s toward the end of their process as well.

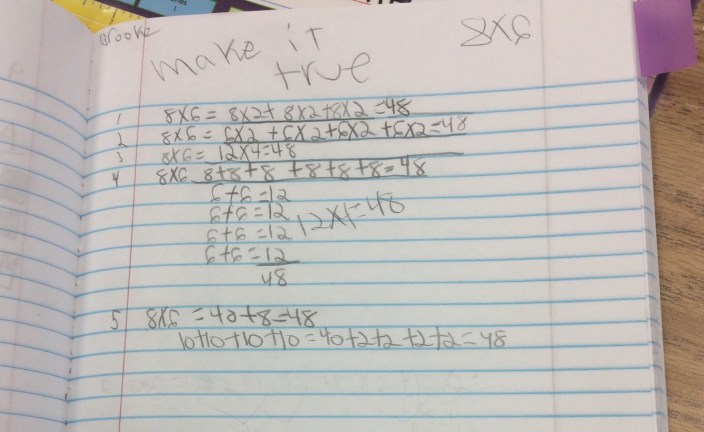

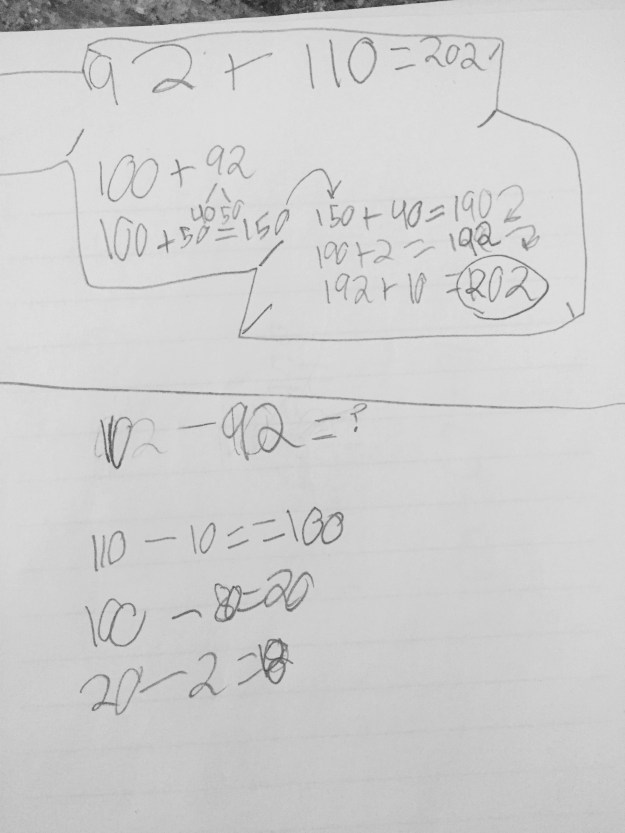

This student used the 100 in so many ways it was awesome! She got to 100, subtracted by 100 and adjusted the answer, and then added up to get to 100.

While the majority of the students chose to subtract a number in the 90’s, this student did not which I find so incredibly interesting. I would love to talk to him more about his number choices!

I didn’t give a clear direction on which operation I wanted them to use, so while most students chose subtraction because that was the problem we ended on, this one played around with both, with the same numbers. I would love to ask this student if 100 was helpful in the same or different way for the two problems.

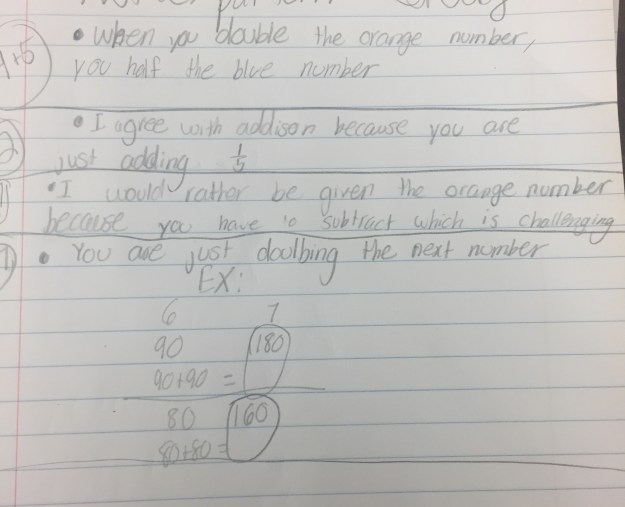

As I said earlier, this is a really tough thing for students to think about because it is looking deeper into their choices and in this case apply it to a new set of numbers. This group was definitely up for the challenge and while I love all of the work above, these two samples are so amazing in showing the perseverance of this group.

In this one, you can see the student started solving the problem and got stuck so she drew lines around it and went on to subtract 10’s until she ran out of time. I love this so much.

This student has so much interesting work. It looks as if he started with an addition problem involving 84, started adding, then changed it to subtraction and got stuck.

This is what I call continuing the conversation. They wrote me notes to let me know Hey, I am not done here yet and I am trying super hard even though there are mistakes here. That is so powerful for our learners. So while there was no “right” answer to my prompt, I got a glimpse into what each student was thinking after the Number Talk which is often hard to do during the whole-group discussion.

If you want to check out how I use journals with other Number Routines, they are in the side panel of all of my videos on Teaching Channel.