Some things I am wondering right now about 3rd grade multiplication…

- When students notice 4 x 3 is the same product as 3 x 4 and say, “The order doesn’t matter,” how do you answer that question?

- Is there a convention for writing 4 groups of 3 as 4 x 3?

- Is there a time, like when moving into division or fraction multiplication and division when the order does matter in solving or in thinking about the context?

Answers I have right now for these questions….

- Right now, since they are just learning multiplication, I ask them what they think and why.

- I think there is a bit of a convention in my mind because the picture changes. Three baskets with 2 apples in each is different than 2 baskets with 3 apples in each. Also, when reading the CCSS it seems that way.

- I am still thinking about division but it makes me think that this would be the difference between partitive and quotative division. I also think when students begin 4th fraction multiplication, they are relating it to what they know about whole number operations, so 4 x 1/2 is 4 groups of 1/2. This seems important.

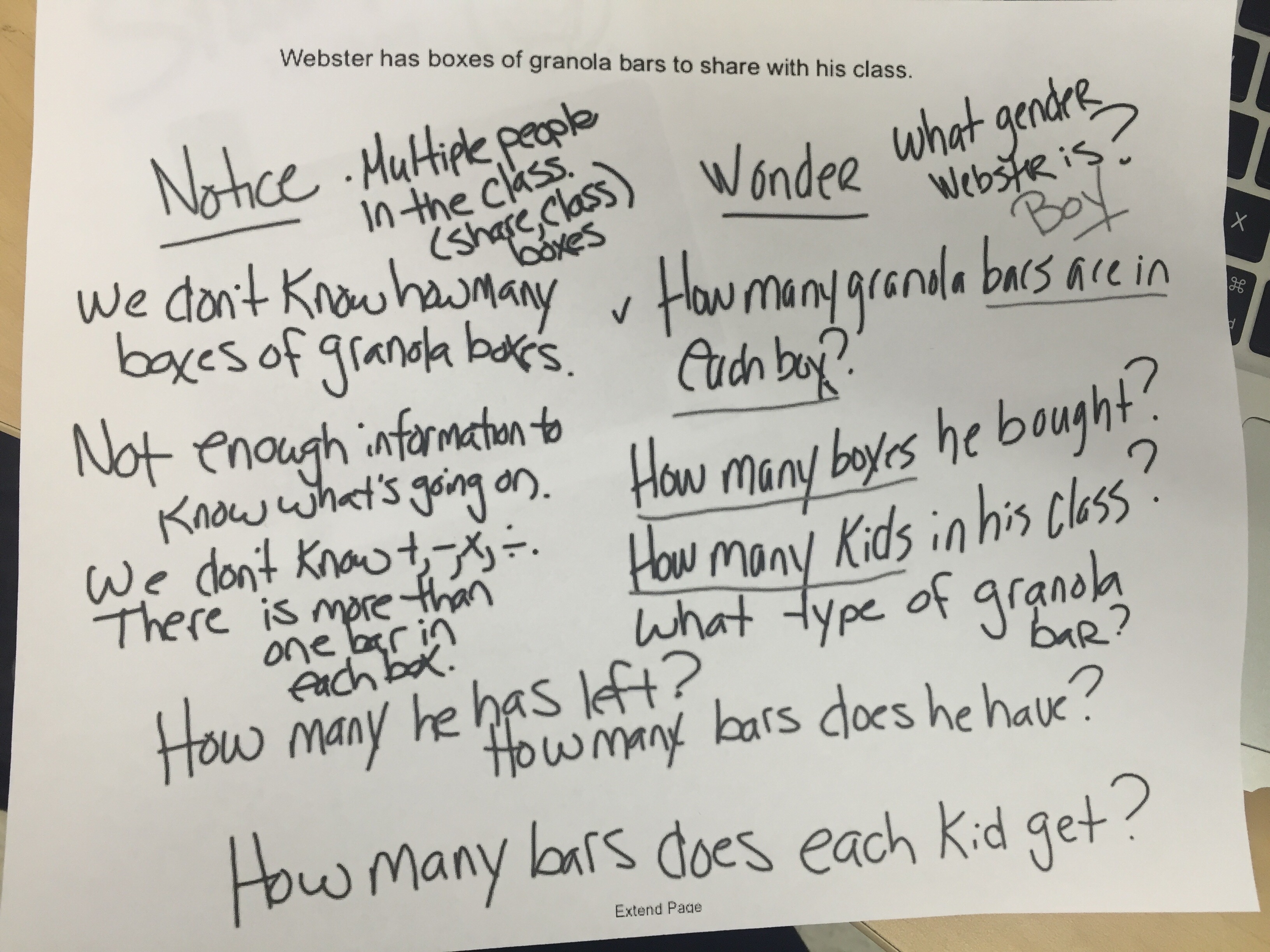

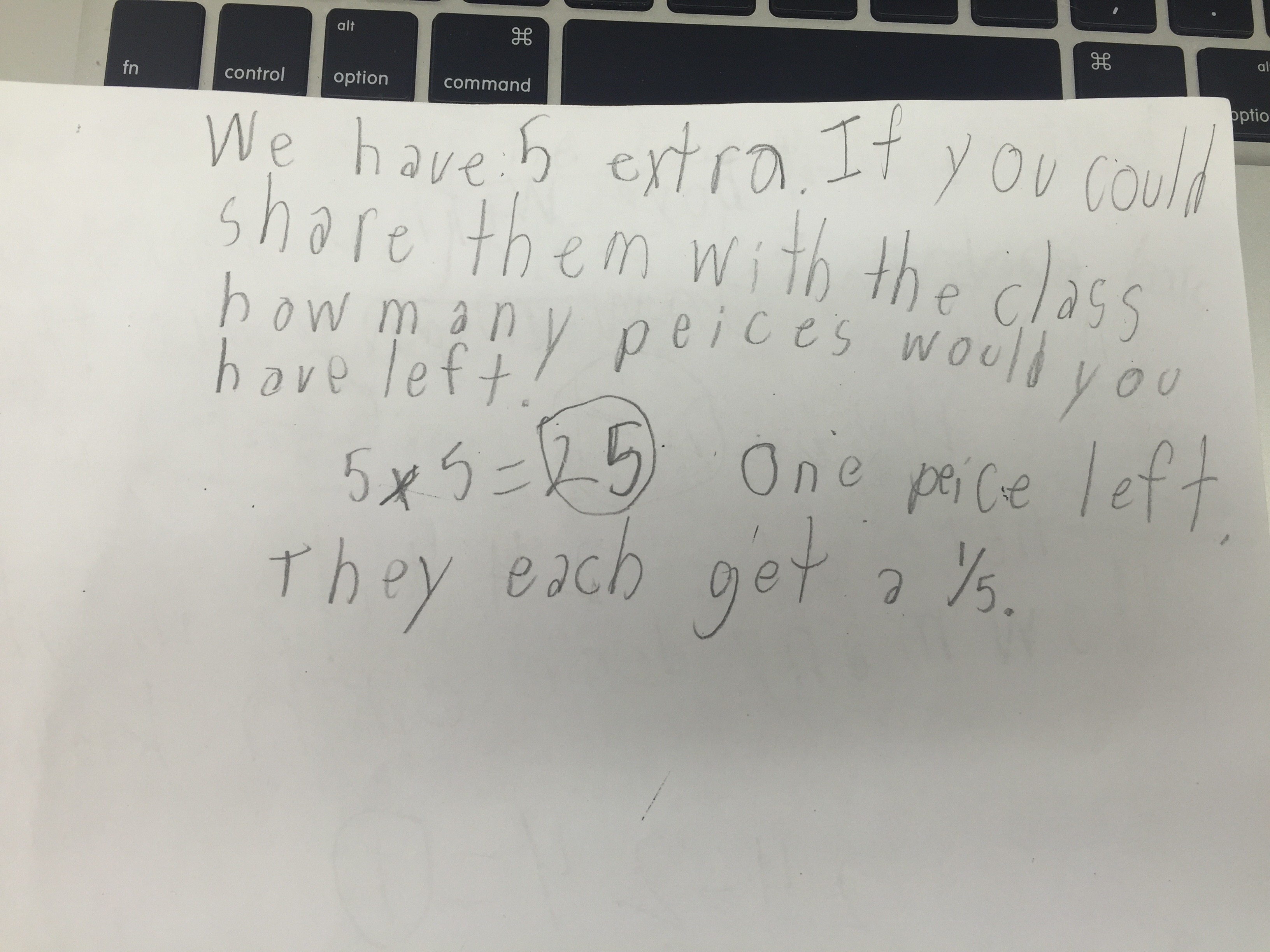

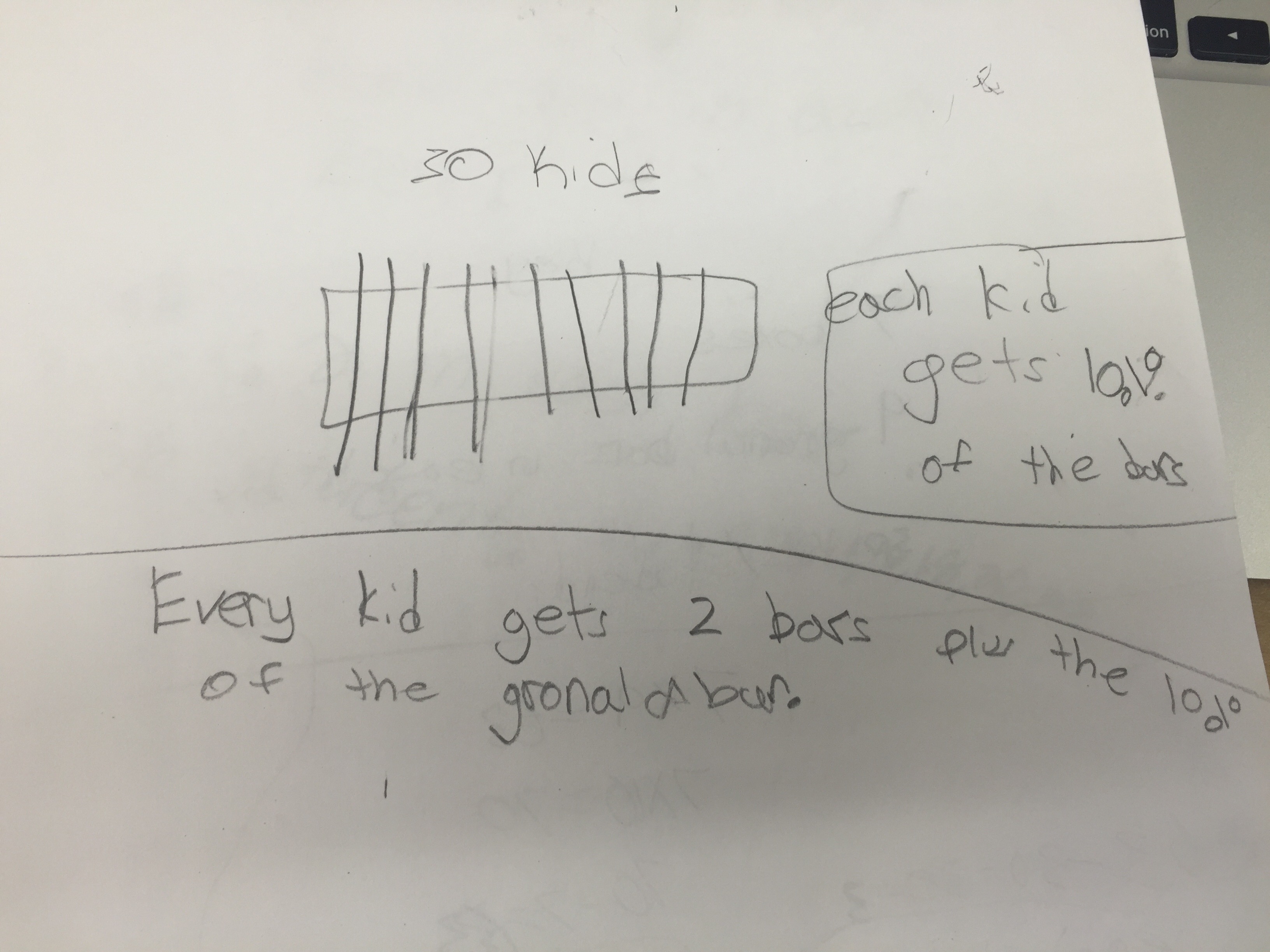

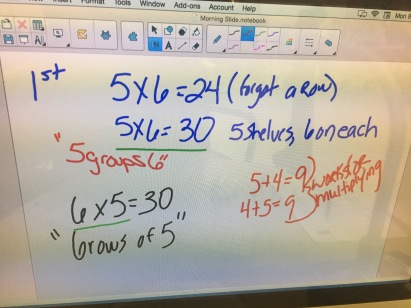

The 3rd grade teachers and I have been having a lot of conversation about these ideas. The students have been doing a lot of dot images and some feel strongly that the two expressions mean the same thing because they can regroup the dots to match both expressions. Others think they are different because the picture changes. All of this seems great, but then students are taking this reasoning to story problems. For example, given a problem such as, There are 5 shelves with 6 pumpkins on each shelf. How many pumpkins are on the shelves? students will represent that as 5×6 or 6×5. Is that a problem for me, not really if they have a way to get the 30, but should it be? I am not sure.

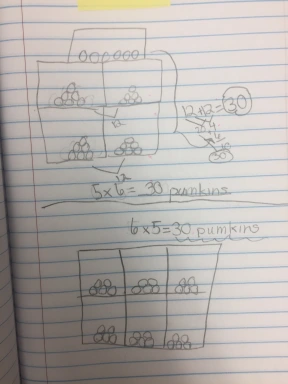

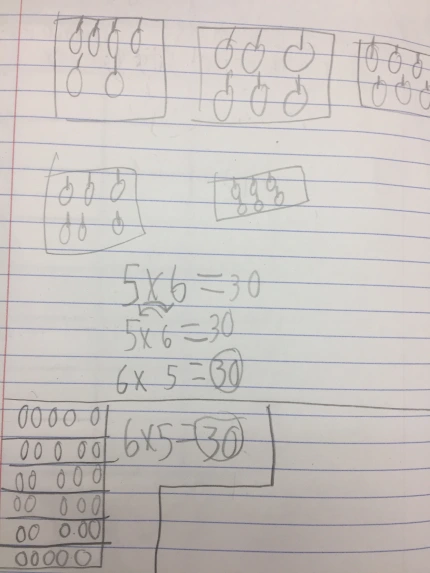

I went into a 3rd grade classroom to try some stuff out. I told them I was going to tell them two stories and wanted them to draw a picture to represent the story (not an art class picture, a math picture) along with a multiplication equation that matched.

1st story: On a grocery store wall there are 5 shelves. There are 6 pumpkins on each shelf.

2nd story: On another wall there are 6 shelves with 5 pumpkins on each shelf.

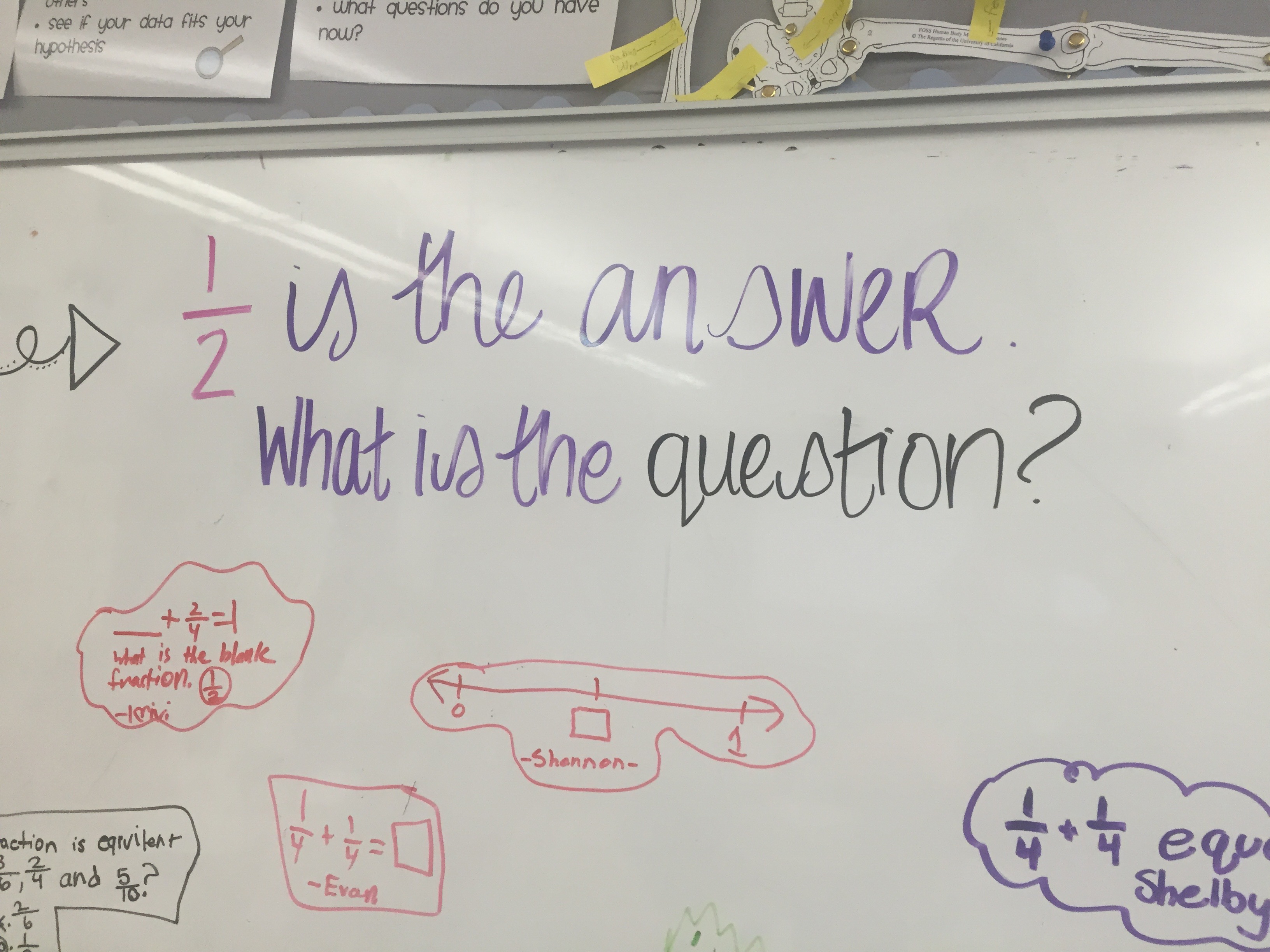

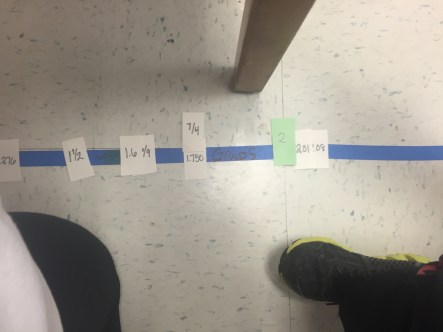

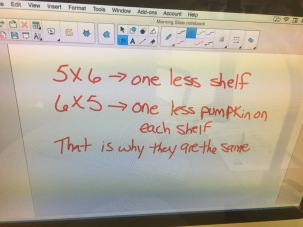

I asked them if the stories were the same and we, as I anticipated, got into the conversation about 5×6 vs 6×5 and what it meant in terms of the story. They talked about 5 groups of 6, related the switching of factors to addition and then some talked about 6 rows of 5.

From this work, many interesting things emerged…

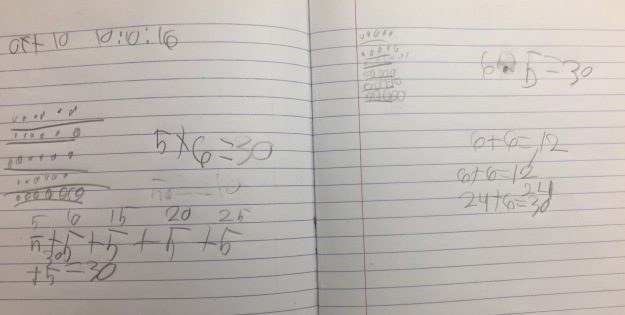

- Some students had different answers for the two problems. They obviously did not see the two expressions as the same because they struggled with 5 groups of 6 as they tried to count by 6’s and forgot a row.

- One student said they liked the second problem better because she could count by 5’s easier than by 6’s.

- Students skip counted by 5’s but added 6’s when finding the 5 groups of 6.

- One student noticed the difference between 5 and 6 and could relate that removing one shelf was just adding a pumpkin to each of the other rows.

- One student showed how he used what he knew about one to switch the factors to make it easier to solve.

But they keep asking Which one is right? and I tell them I don’t have an answer for them. I just keep asking them:

Is the answer the same?

Is the picture the same when you hear the story?

After chatting with Michael Pershan yesterday, I am still in a weird place with my thinking on this and I think he and I are in semi-agreement on a few things (correct me if I am wrong Michael) …Yes, I think “groups of” is important to the context of a story. I want students to know they can find the answer to these types of problems by multiplying. I want students to be able to abstract the expression and change the order of the factors if they know it will make it easier to solve BUT what I cannot come to a clear decision on is…

If we should encourage (or want) students to represent a problem in a way that matches the context AND if the answer is yes, then is that way: a groups of b is a x b?