In 3rd grade, students come to understand fractions as numbers. They count by them and locate them on a number line just like whole numbers. However, once they start operating with fractions in 4th and 5th grade, they tend to set aside everything they understand about whole number operations and treat fractions as numbers with their own set of ‘rules.’ I can think of many reasons why this happens, but my current wondering is how we can create more opportunities for students to make connections between their understanding of whole number and fraction operations.

Why Connections?

So many times I see students not realize all of the wonderful things they know that would be helpful in their new learning. I believe this is because we just don’t spend enough time making connections explicit to support this transfer.

One of my favorite papers on the importance of practicing connections (linked in the citation) describes the ‘why’ so nicely…

“Although there may have been a time when rote learning of facts and procedures was sufficient as an outcome for education, that is certainly not the case today. Anyone with a phone can Google to find facts that they have forgotten. But gaps in thinking and understanding are not easily filled in by Internet searches. Increasingly, we value citizens who can think critically, coordinate different ideas together, solve novel problems, and apply their knowledge in all kinds of situations that do not look like ones they have previously encountered. In short, we want to produce students with deep understanding of the complex domains that constitute the modern knowledge landscape (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018).”

“Studies show that expert knowledge in a domain is generally organized around a small set of core concepts (e.g., Lachner and Nückles 2015) that imbue coherence to even wicked domains. Because they are highly abstract and interconnected with other concepts, core concepts must be learned gradually, over extended periods of time and through extensive practice. As students practice connecting concepts with other concepts, contexts, and representations, these core concepts become more powerful and students’ knowledge becomes more transferable (e.g., Baroody et al. 2007; National Council for Teachers of Mathematics 2000; Rittle-Johnson and Schneider 2015; Rittle-Johnson et al. 2001).”

Fries, L., Son, J.Y., Givvin, K.B. et al. Practicing Connections: A Framework to Guide Instructional Design for Developing Understanding in Complex Domains. Educ Psychol Rev 33, 739–762 (2021).

Subtracting Whole Numbers

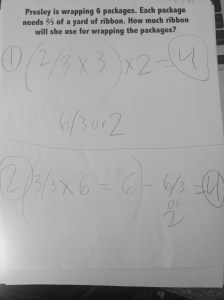

In 4th grade, students have been decomposing fractions into sums of fractions with the same denominator and justifying their decompositions. They naturally leveraged their understanding of whole number decomposition, but when we gave them a problem to add or subtract, they quickly looked for a ‘rule’ to find the sum or difference. And, while we want them to generalize these operations, as the numbers get more complex –mixed numbers and unlike denominators – a memorized rule absent understanding doesn’t help students reason about the problem.

The lesson last week had students representing their fraction addition and subtraction on the number line, but that representation was causing some students more angst than support so we decided to use the problems from the lesson, but focus on the connection to whole number operations instead of forcing only the number line on them.

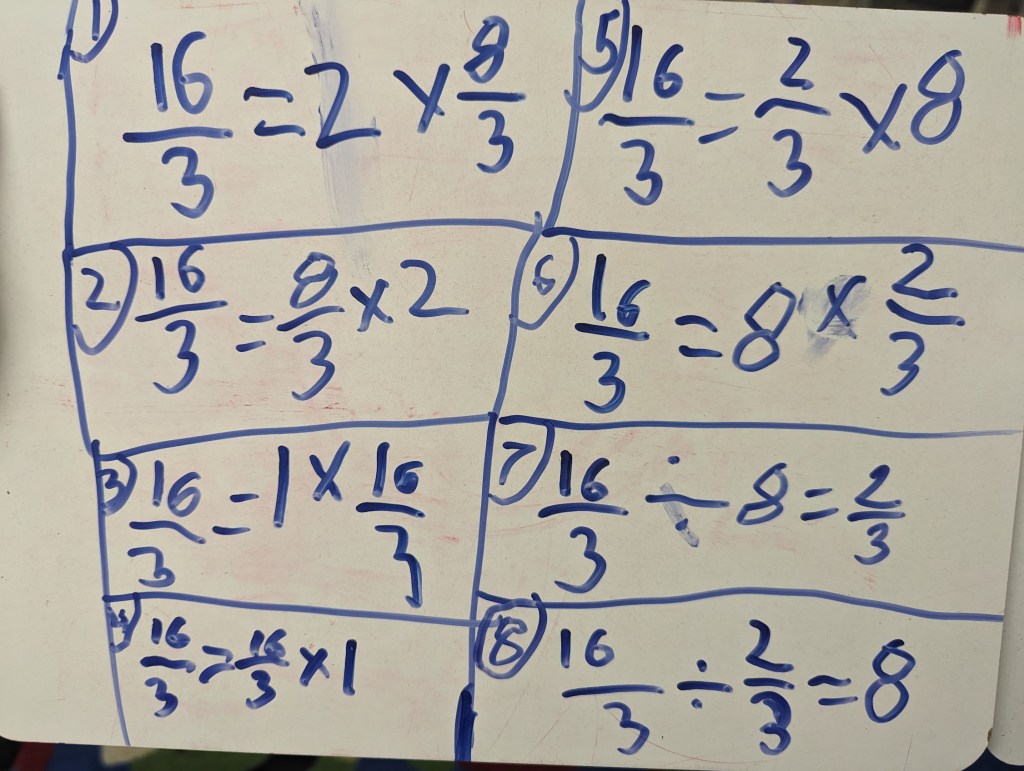

On their whiteboards, we asked them to record all the ways they think about and can represent 13–6=?. We saw a nice mix of ideas like removing items (base 10 blocks), hopping back on a number line, decomposing 6 and subtracting in parts, adding up (relationship to addition), and the algorithm – which made them all chuckle because after ‘borrowing’ it ended up being the same problem.

Connection to Subtracting Fractions

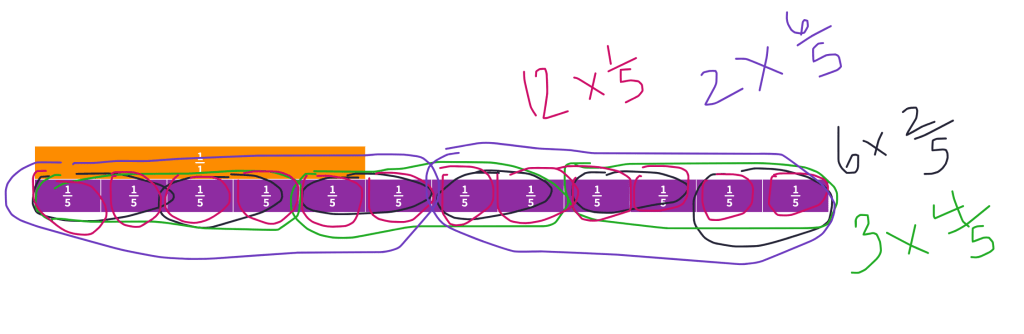

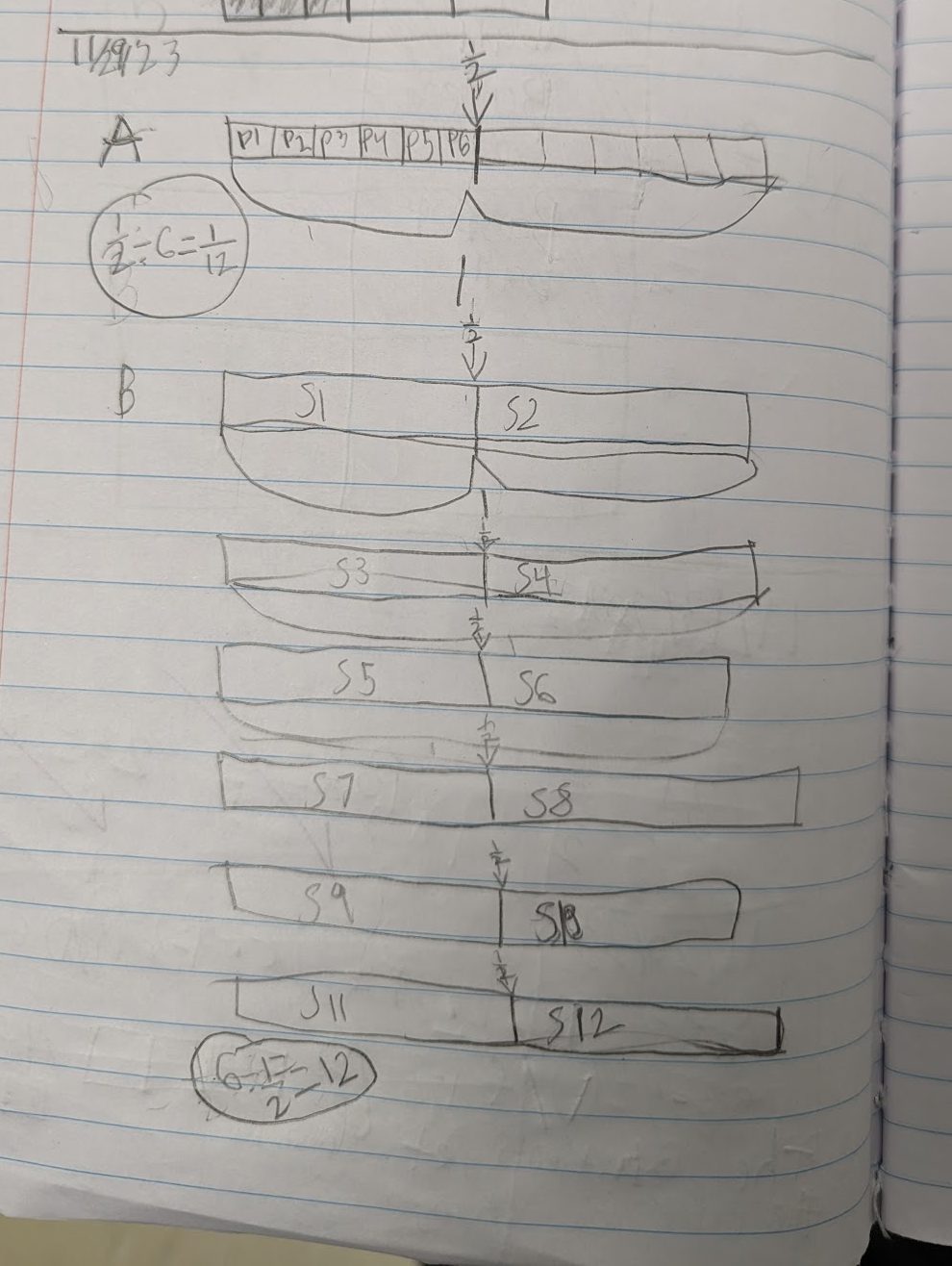

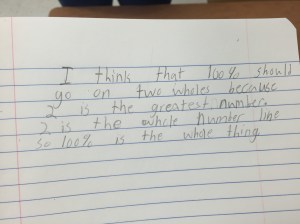

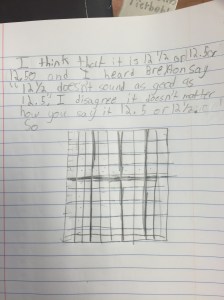

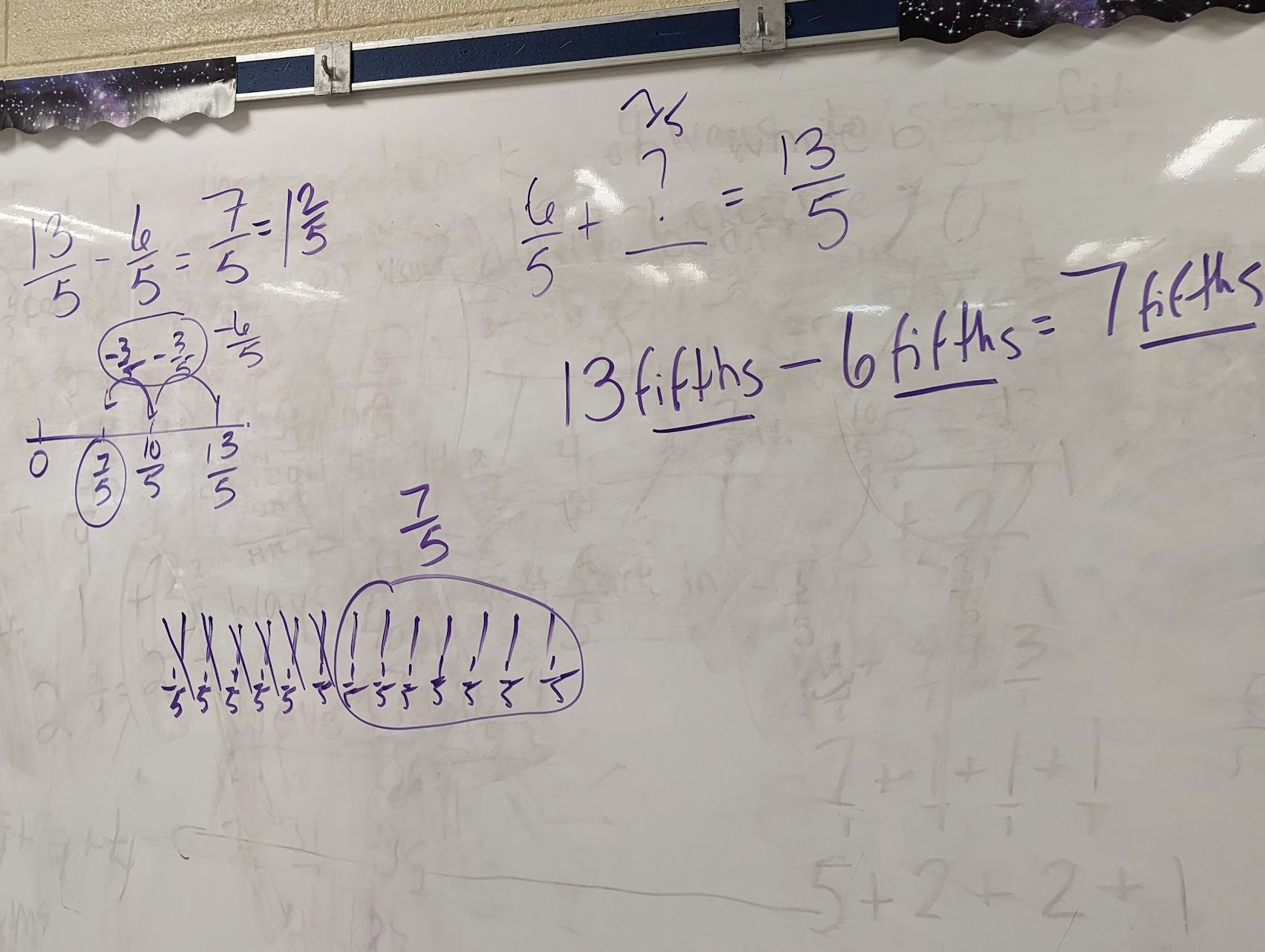

We shared these ideas out, recorded them on the board for reference, and then asked them to erase their whiteboards and do the same thing for 13/5 – 6/5=?. Students shared the methods and representations they used and we discussed how they were like the ones they used for whole numbers. It took no time for someone to say ‘It is exactly the same, just fifths.’ One student wrote it out in words so the discussion of the change in units was perfect.

Applying the Strategies

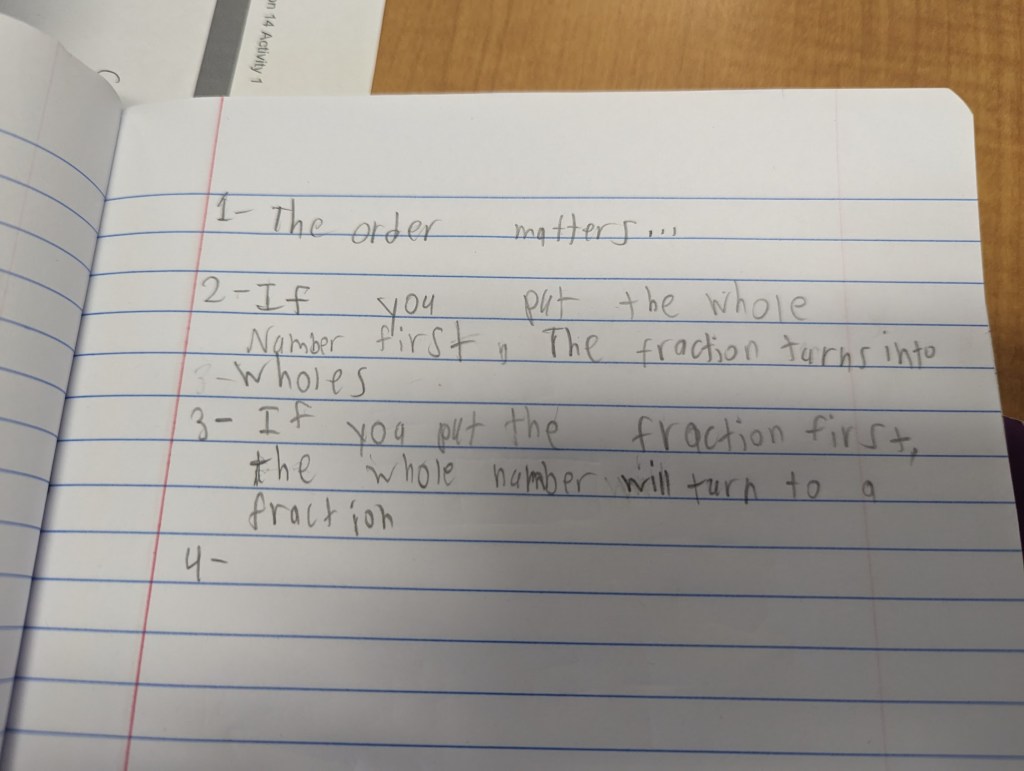

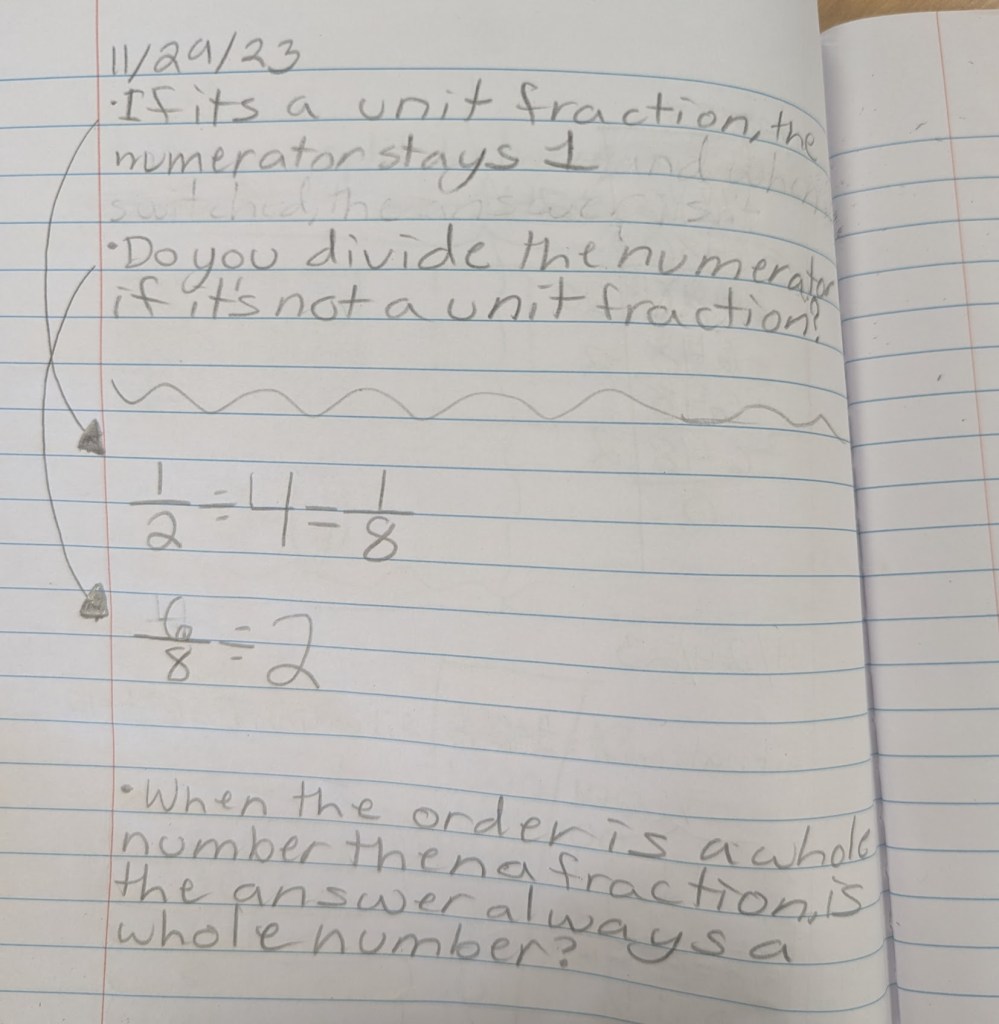

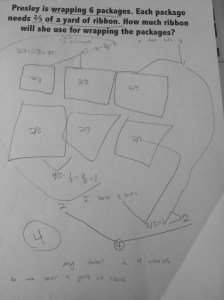

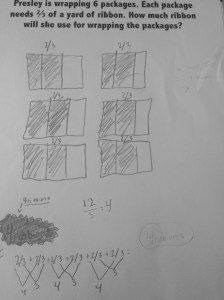

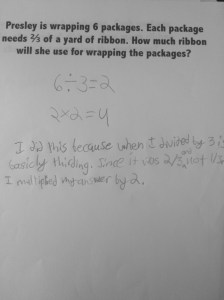

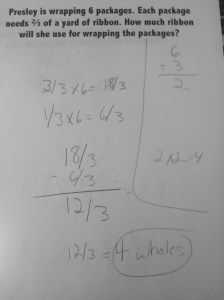

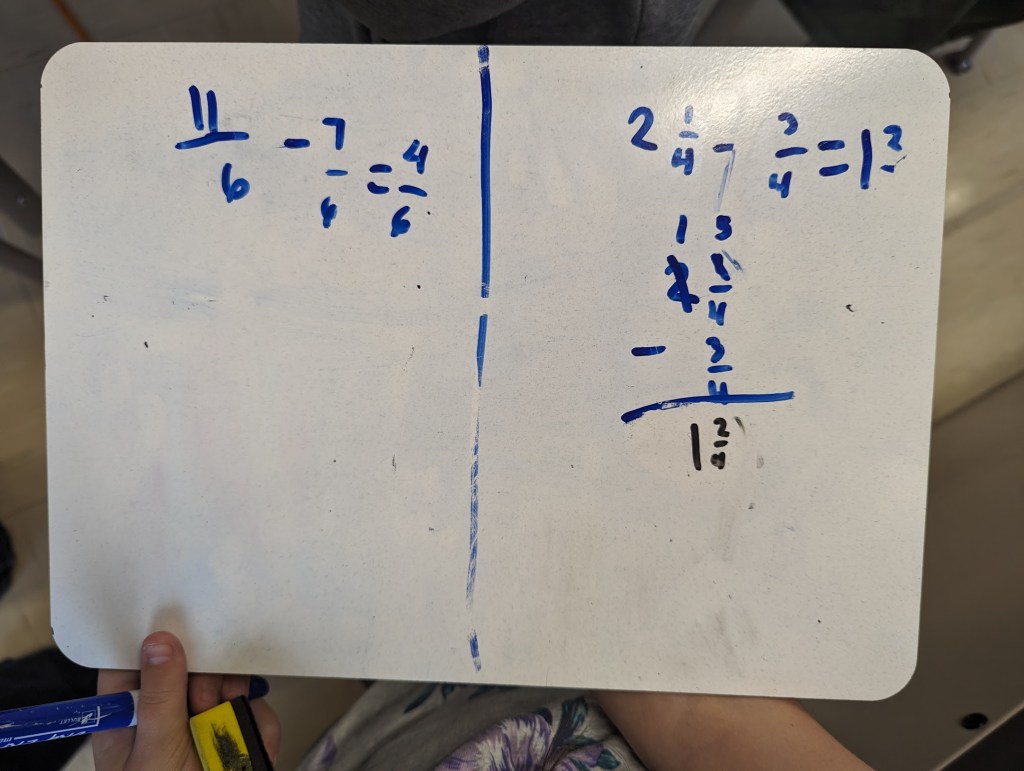

Next we wanted students to practice a couple of problems, including mixed number subtraction where the first fraction numerator was less than the second. We were excited to see many of the same methods being used and some students really got into showing it multiple ways.

Try it out!

Any 4th and 5th grade teachers out there who want to try this out, I would love to hear what you learn about student thinking and what students learn about important connections in math class!