Recently, our 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade teachers had the opportunity to chat math for 2 hours during a Learning Lab held on a professional development day. It was the first time we had done a vertical lab and it felt like perfect timing as 3rd and 4th grade would soon be starting their fraction unit and 5th would be entering their decimal unit. Prior to the meeting, we read the NCTM article, “Identify Fractions and Decimals on a Number Line” by Meghan Shaughnessy, so we started the meeting discussing ideas in the article. We then jumped into playing around with clothesline number lines and double number lines, discussing what they could look like at each grade level based on where students are in the fractional thinking.

I have co-taught number line lessons in both 5th grade and Kindergarten this year, but both were a bit different in not only number, but organization. In 5th grade we used one clothesline with the whole class, while in Kindergarten we used tape on the floor and students worked in small groups. Leigh, 5th grade teacher, was interested in trying the small group number lines on the floor. As we planned the lesson, the one thing we thought would be difficult about having small groups is getting around to each group to hear their conversations, especially when we were planning cards purposefully to address misconceptions and misunderstandings. However, knowing we would have the two of us circulating, as well as two 3rd grade teachers who wanted to see the lesson (yeah!), we knew we had plenty of eyes and ears around the room to hear the math conversations.

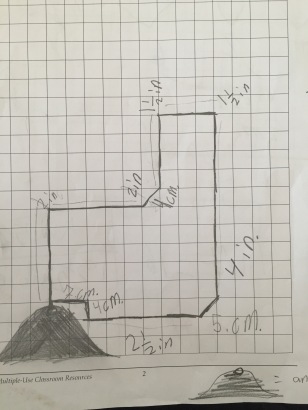

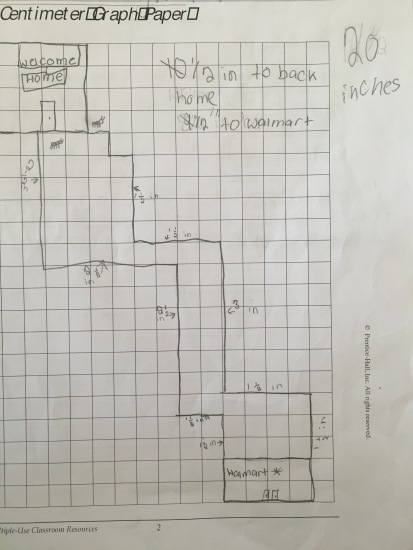

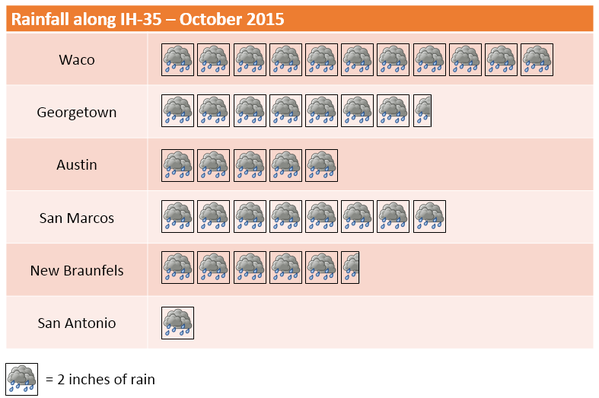

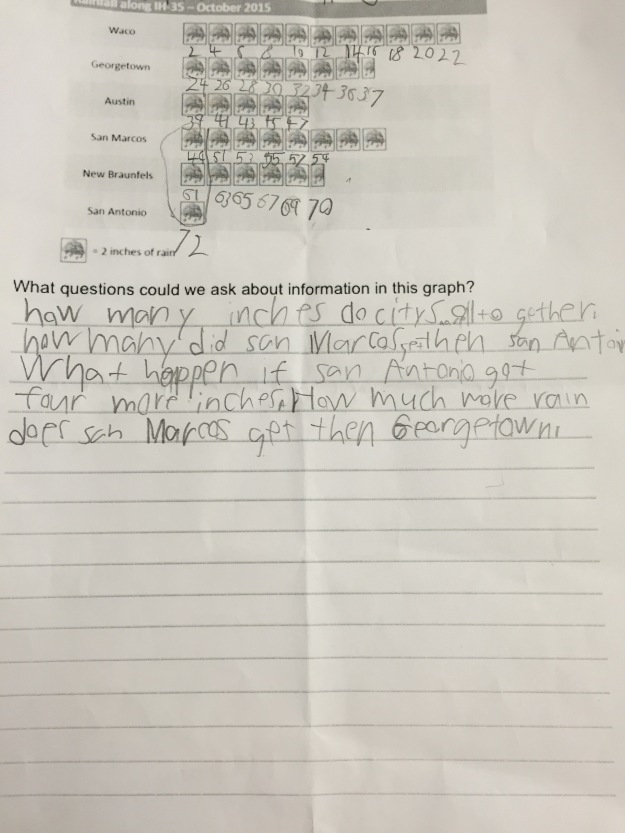

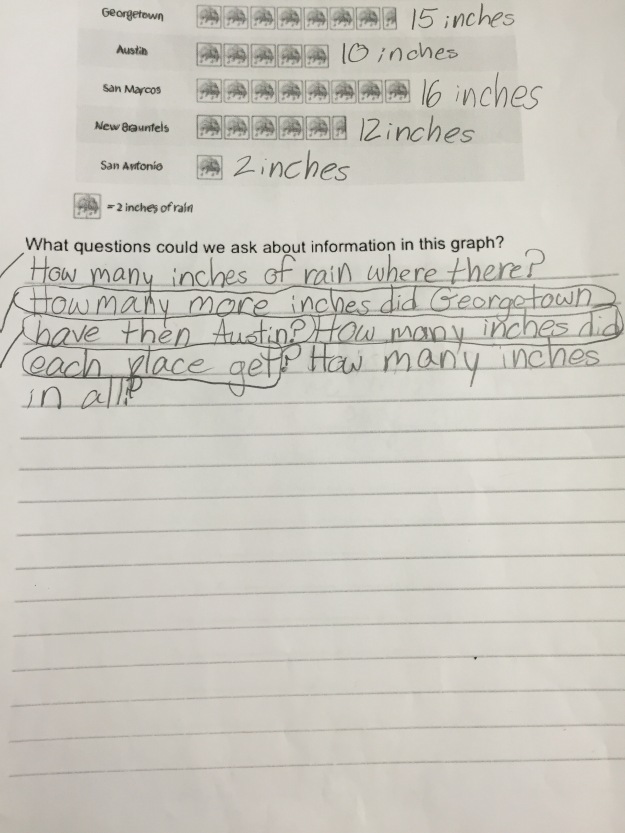

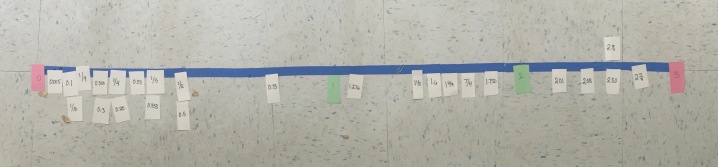

During the lesson, in groups of three, students placed 24 cards on their number line. There were two sets of cards, so after placing all of their cards, each group visited a number line with a different set of cards to discuss. Instead of boring you with all of the number choices we made, here are a few of the choices in cards and the reason(s) we chose them:

1/3 and .3: Students often think these two are equivalent so before the decimal unit we were curious to see how they were thinking around that idea and how they used what they knew about fractions or percents to reason about it.

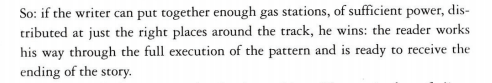

0.3, 0.33, 0.333, 1/3: The 1/3 and .333 were there to think about equivalency, while the others were there to think about what is the same in each and how much more each decimal has to make it larger. Which you can see caused some confusion here:

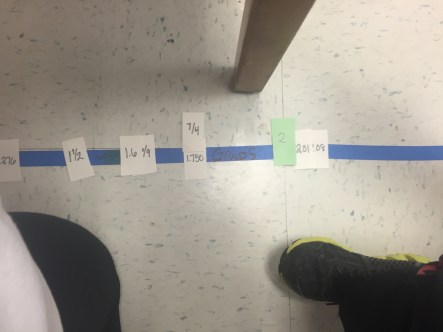

2.01 and 2.08: We were curious about the distance they put between these two cards.

1 6/9 and 1.6: We wanted to see how students compared fractions and decimals when they can’t easily convert 6/9 into a decimal. Then, if they began thinking 6/9 and 6/10, how would they decide on the larger fraction and then how much distance do they put between them?

The group below practically had them on top of one another:

While this group had a bit of a space between them:

2.8 and 2.80: Tenths and hundredths equivalency. They all seemed to handle this with ease.

.005 and 1/100: Curious to see the placement in relation to the other numbers. This 1/100 is close to 0 but I wonder about it in relation to the .2. Definitely a conversation worth having!

2.8 and 2 7/8: To see how they compared the 7/8 to the 8/10.

After they visited other number lines, they had a chance to meet with that group and discuss card placements they agreed with and placements they did not. Groups then made adjustments accordingly…

Here was a group’s completed number line and my first stab at panoramic on my phone!

The journal entry we left them with was, “Which cards were the most difficult to place on the number line? Why?” Many were just as we suspected.

The conversation as I walked back over to the other building with the 3rd grade teachers was, what does this look like in 3rd grade? Could we use array images to place on the line instead of the fractions? Could the pictures include over 1 whole? What whole numbers would we use? Do we play with equivalent pictures with different partitioning? Being mindful of the students’ second grade fraction exposure, below, we are planning on trying out something very soon! I am thinking the cards like these on Illustrative, with the pictures but no fraction names at this point.

Partition a rectangle into rows and columns of same-size squares and count to find the total number of them.

Partition circles and rectangles into two, three, or four equal shares, describe the shares using the words halves, thirds, half of, a third of, etc., and describe the whole as two halves, three thirds, four fourths. Recognize that equal shares of identical wholes need not have the same shape.