Each month, teachers choose their Learning Lab content focus for our work together. Most months, 1/2 of the grade level teachers choose to have a Math Learning Lab while the other 1/2 work with Erin, the reading specialist in an ELA Learning Lab. This month, however, we decided to mesh our ELA and Math Labs to do some mathematizing around children’s literature in Kindergarten and 1st grade! This idea was inspired by a session at NCTM last year, led by Allison Hintz, that left me thinking more about how we use read-alouds in our classrooms and the lenses by which students listen as we read.

In The Reading Teacher, Hintz and Smith describe mathematizing as, “…a process of inquiring about, organizing, and constructing meaning with a mathematical lens (Fosnot & Dolk, 2001). By mathematizing books commonly available in classroom collections and reading them aloud, teachers provide students with opportunities to explore ideas, discuss mathematical concepts, and make connections to their own lives.” Hintz, A. & Smith, T. (2013). Mathematizing Read Alouds in Three Easy Steps. The Reading Teacher, 67(2), 103-108.

Erin and I have literally been talking about this idea all year long based on Allison’s work. We discussed the ways we typically see read-alouds used, such as having a focus on a particular text structure or as a counting book in math.

As Erin was reading Kylene Beers & Robert Probst’s book, Reading Nonfiction she pointed me to a piece of the book on disciplinary literacy which automatically had me thinking about mathematizing.

Beers refers to McConachie’s book Content Matters (2010), in which she defines disciplinary literacy as, “the use of reading, reasoning, investigating, speaking, and writing required to learn and form complex content knowledge appropriate to a particular discipline.” (p.15) She continues to say, “…disciplinary literacy “emphasizes the unique tools that experts in a discipline use to engage in that discipline” (Shanahan and Shanahan 2012, p.8).

As I read this section of the book, my question became this…(almost rhetorical for me at this point)

Does a student’s lens by which they listen and/or read differ based on the content area class they are sitting in?

For example, when reading or listening to a story in Language Arts class, do students hear or look for the mathematical ideas that may emerge based on the storyline of the book or illustrations on the page? or Do students think about a storyline of a problem in math class or are they simply reading through the lens of “how am I solving this?” because they are sitting in math class?

Mathematizing gets at just this. To think about this more together, Erin and I decided to jump right into the children’s book The Doorbell Rang by Pat Hutchins. Erin talked about the ideas she had for using this in an ELA class, I talking through the mathematical ideas that could emerge in math class, and then we began planning for our K/1 Learning Lab where we wanted teachers to think more about this idea with us! We were so fortunate to have the opportunity to chat through some of our thoughts and questions with Allison the day before we were meeting with the teachers. (She is just so wonderful;)

The first part of our Learning Lab rolled out like this…

We opened with this talking point on the board:

“When you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.”

Everyone had a couple of minutes to think about whether they agreed, disagreed, or were unsure about the statement. As with all Talking Points activities, each teacher shared as the rest of us simply listened without commenting. The range of thoughts on this was so interesting. Some teachers based it on a particular content focus, some on personal connections, while I thought there is a slight difference between the words “look” and “see.”

After the Talking Point, Erin read The Doorbell Rang to the teachers and we asked them to discuss what the story was about with a partner. This was something Allison brought up that Erin and I had not thought about in our planning. I don’t remember her exact wording here, but the loose translation was, “Read for enjoyment. We want students to read for the simple joy of reading.” While Erin and I were so focused on the activity of exploring the text through a Math or ELA lens, we realized that the teachers first just needed to enjoy the story without a purpose.

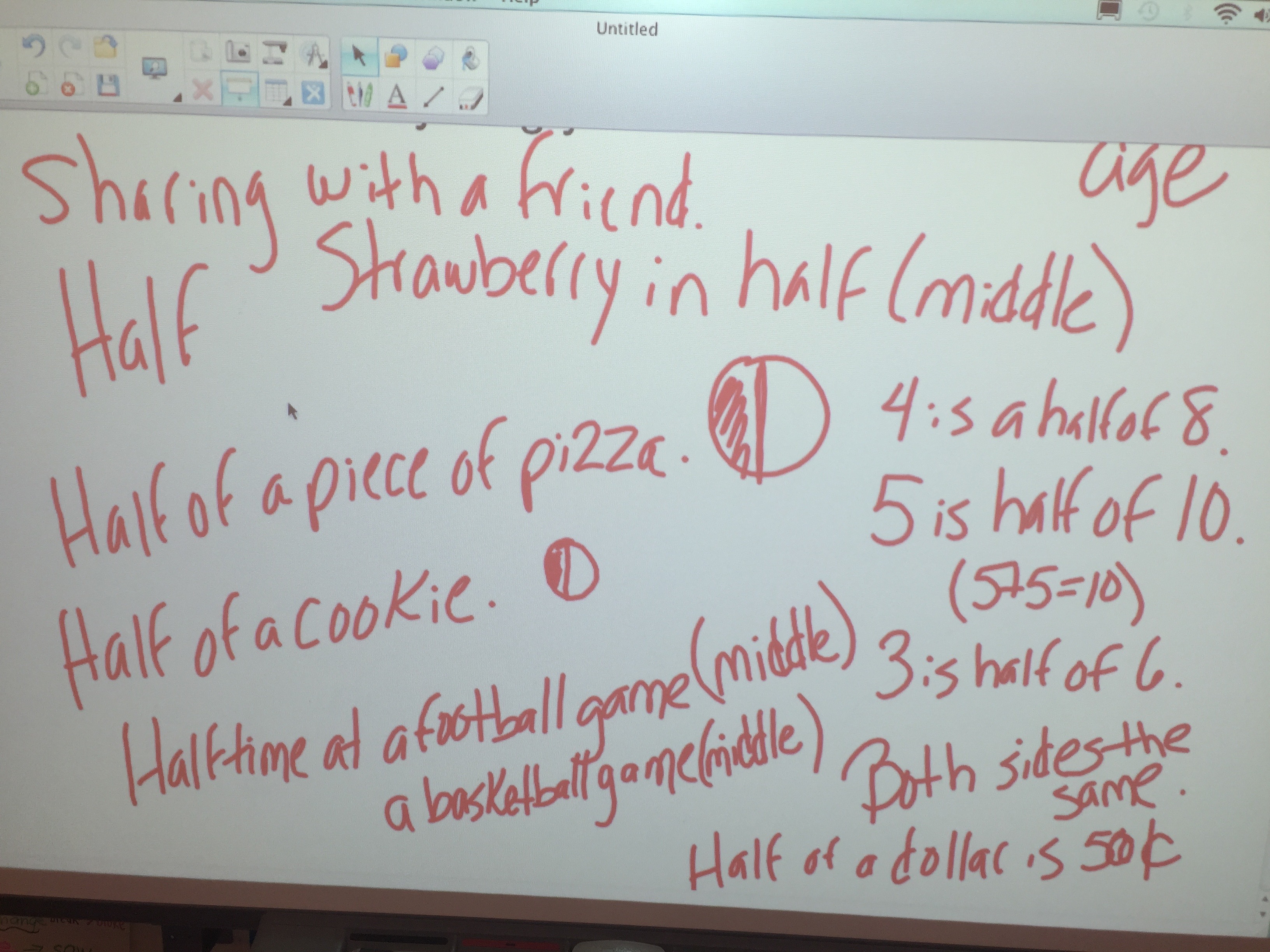

For the second reading of the book, we gave each partner a specific lens. This time, one person was listening with an ELA lens while, the other, a Math lens. We asked them to jot down notes about what ideas could emerge through these lenses with their classes. You may want to go back and watch the video again to try this out for yourself before reading ahead!

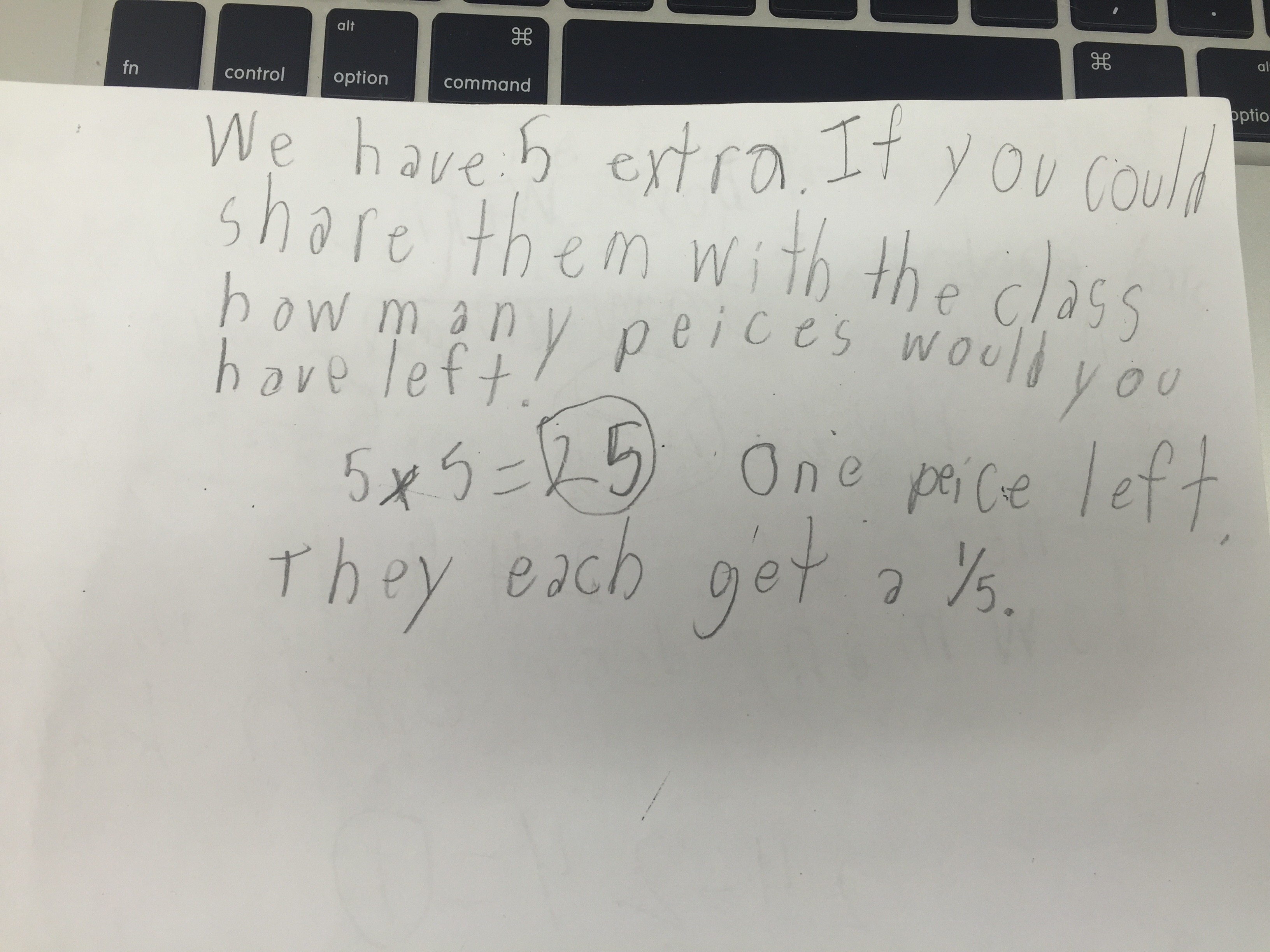

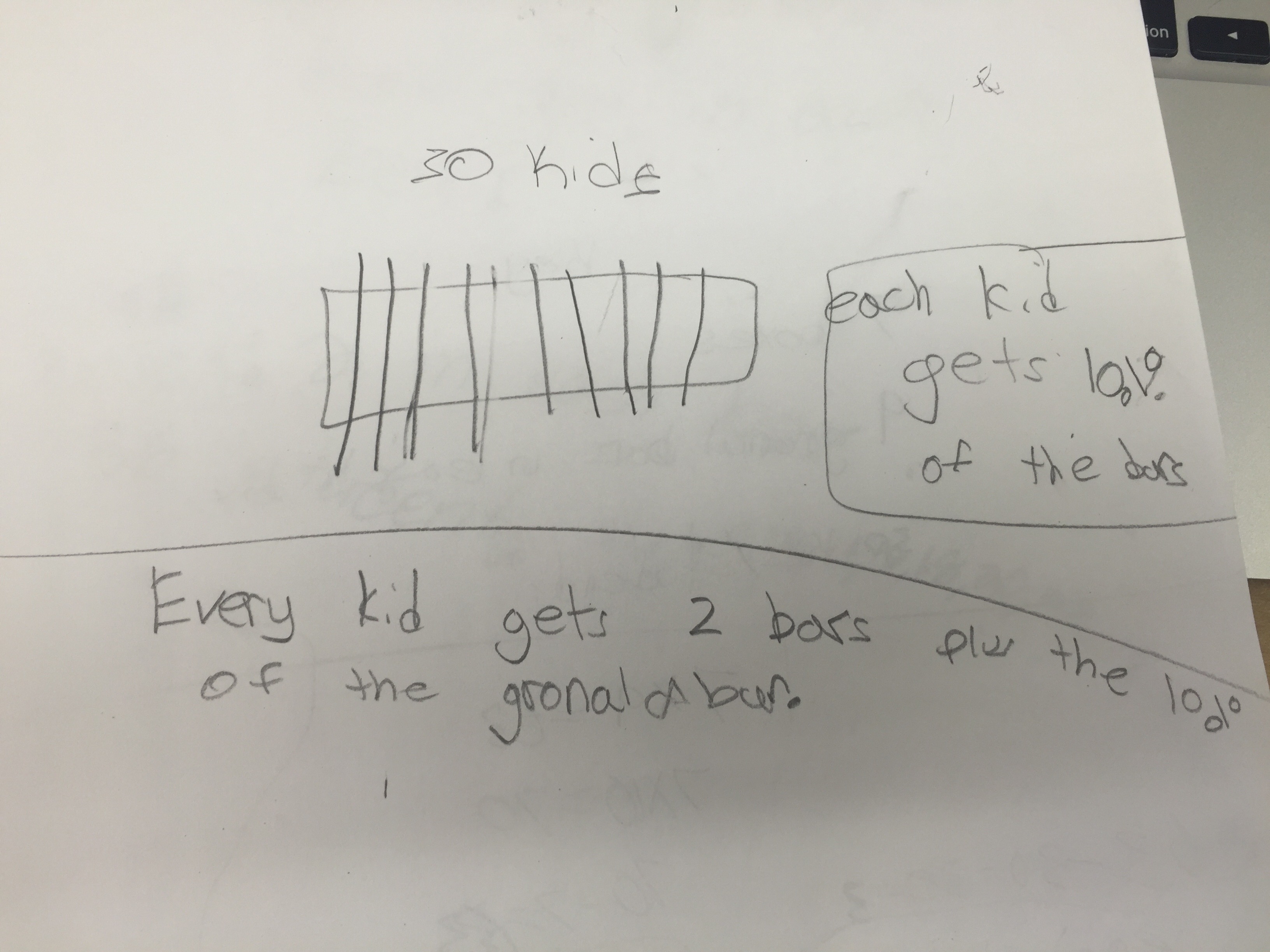

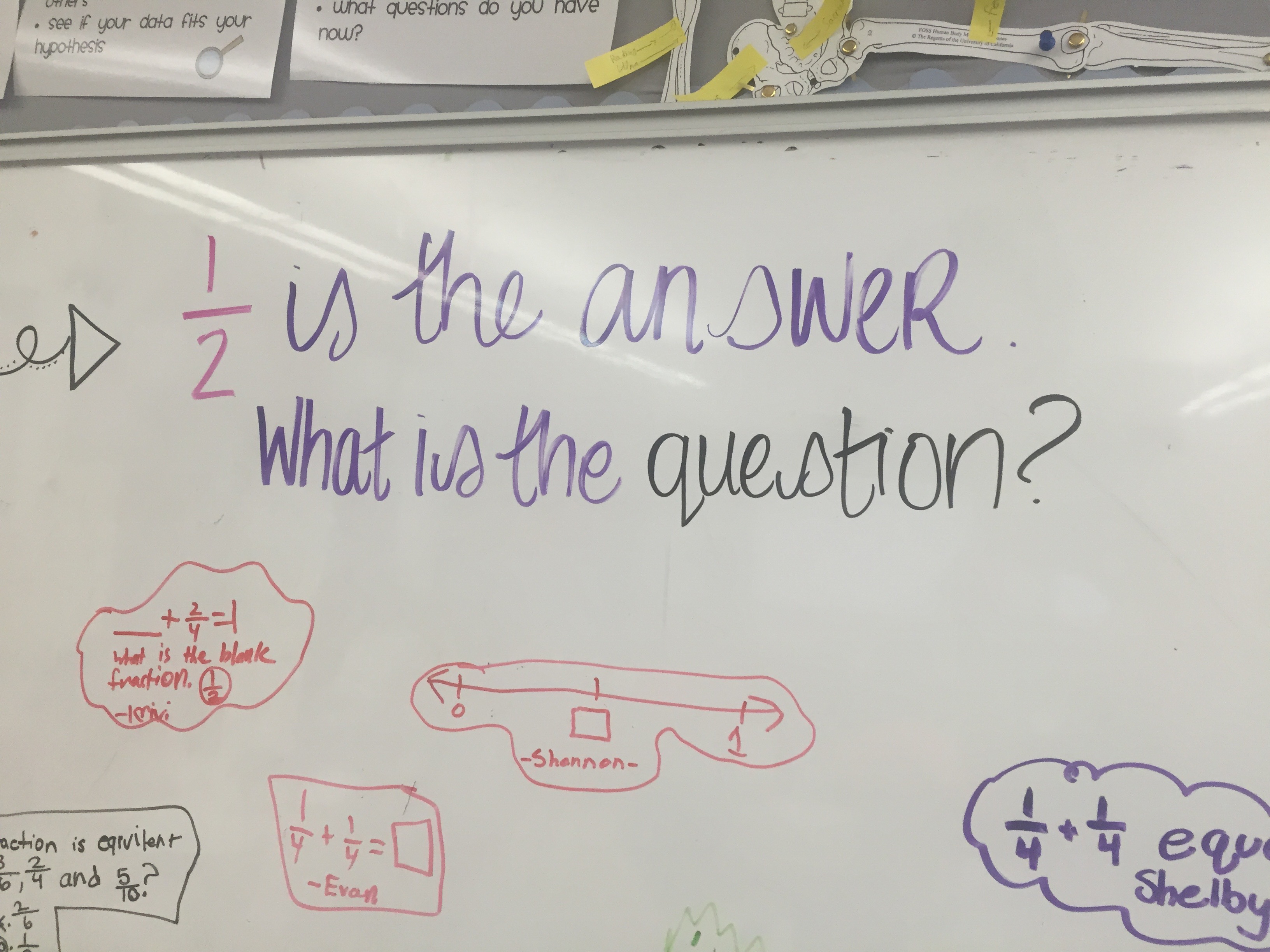

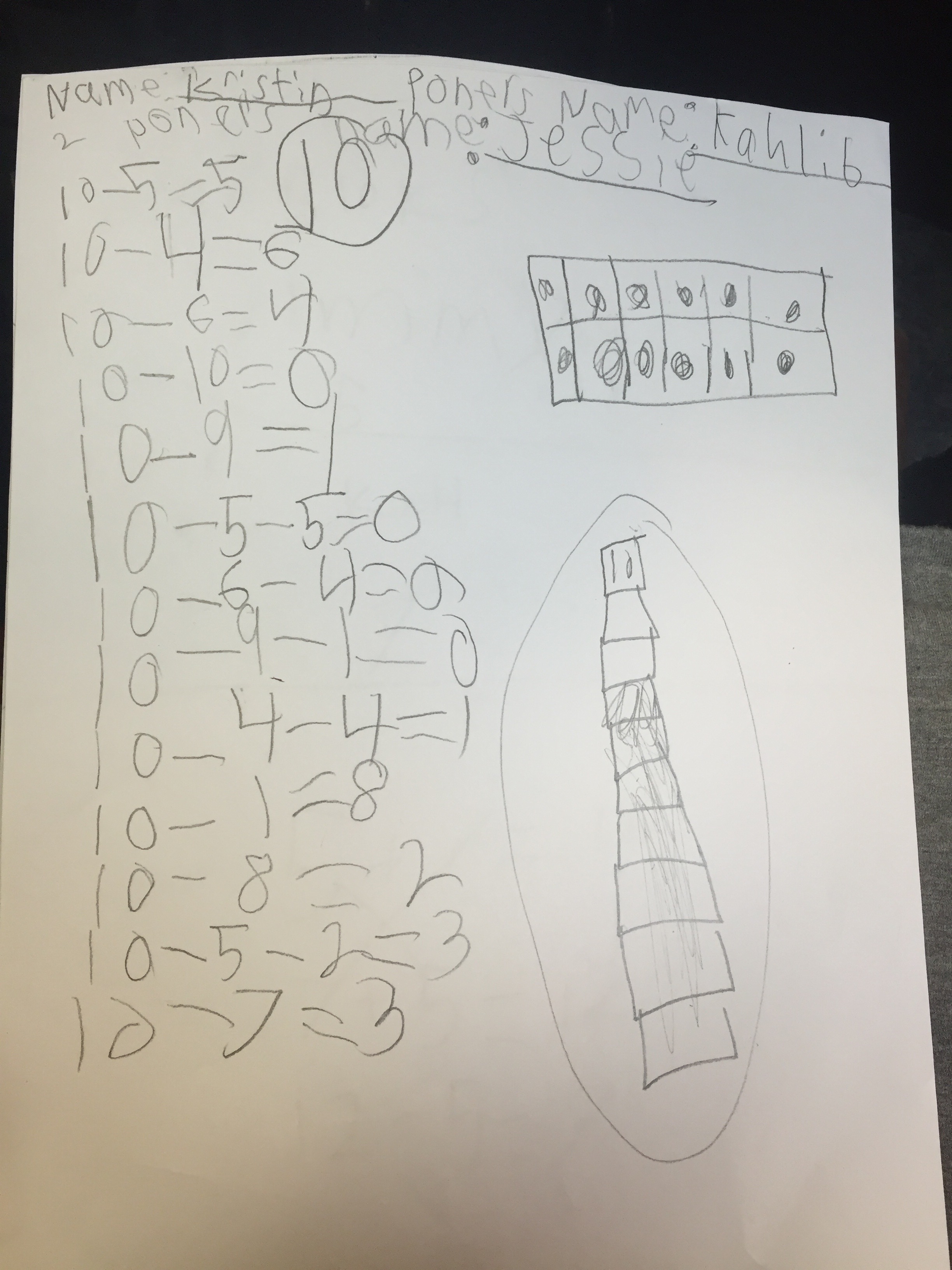

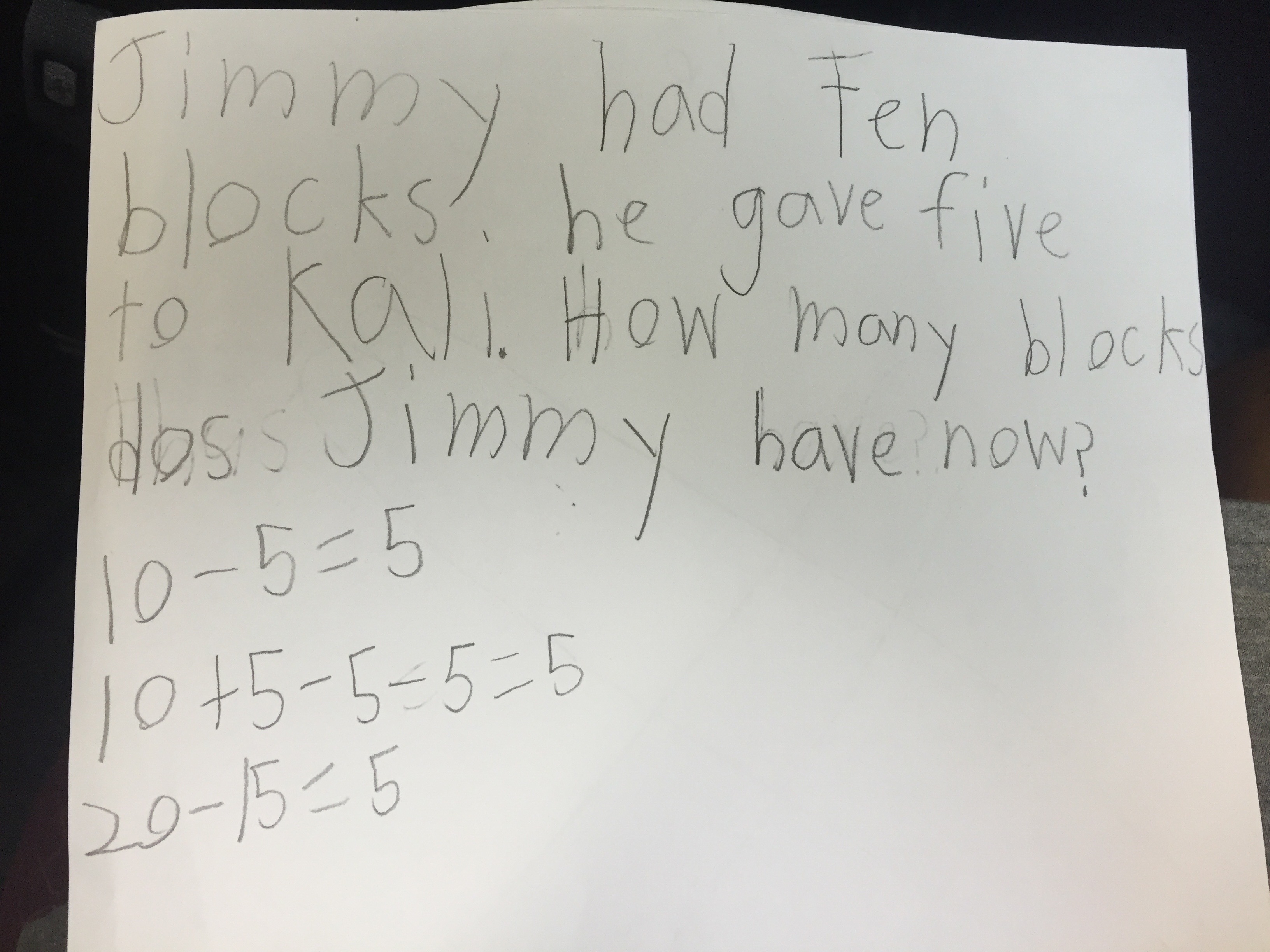

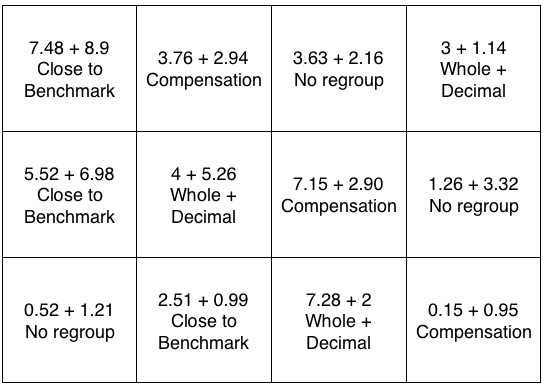

Here are some of their responses:

Together we shared these ideas and discussed how the ELA and Math lenses impacted one another. A question we asked, inspired by Allison, was “Could a student attend to the math ideas without having a deep understanding of the story?”

Many questions came up:

- Could we focus on text structures and the math in the same lesson?

- Could we start with an activity before reading the book, like a probable passage?

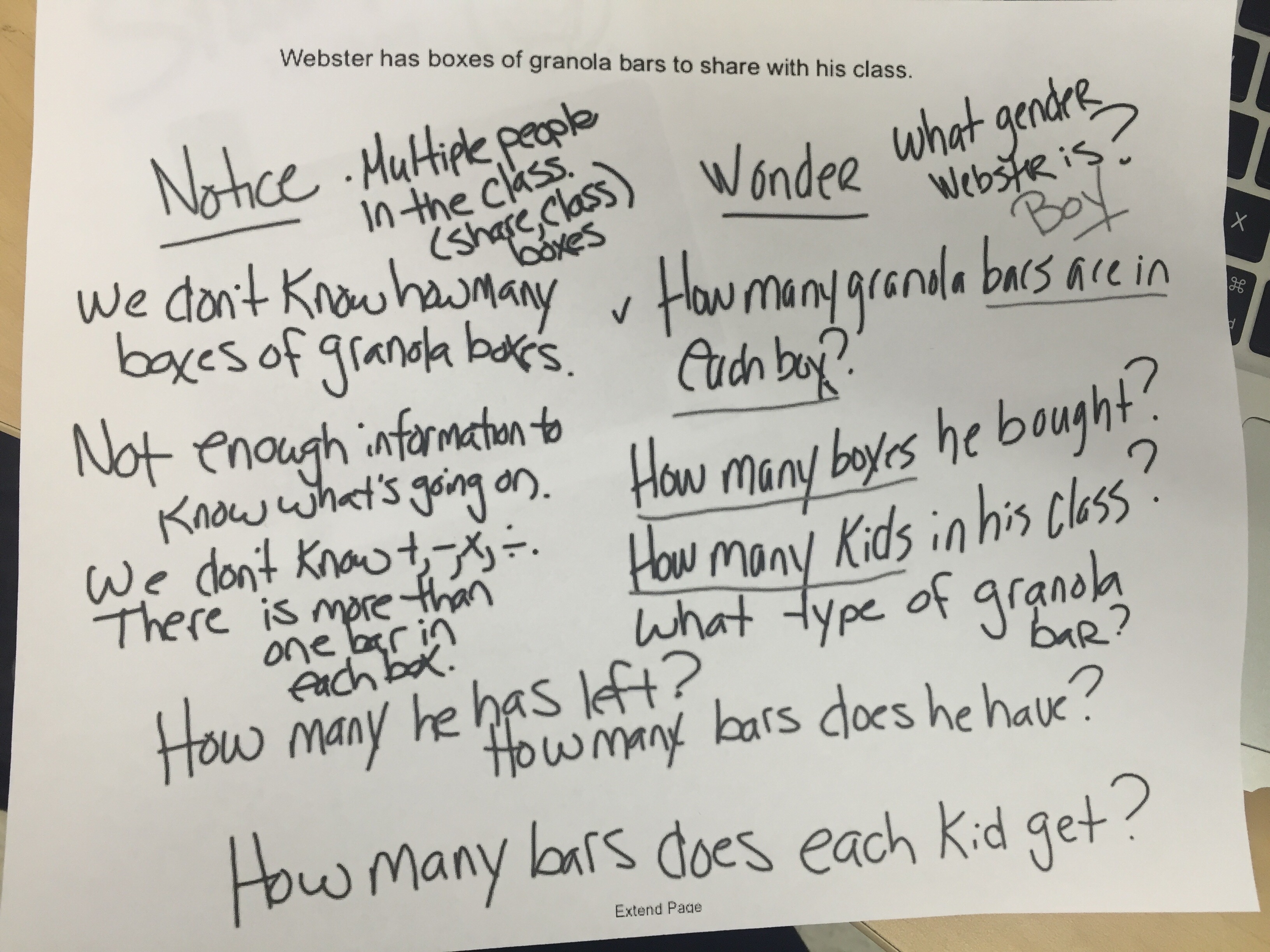

- Would an open notice/wonder after the first reading allow the lens to emerge from the students? Do they then choose their own focus or do we focus on one?

- How could focusing on the problem and solution get at both the ELA and Math in the book?

- How could we use the pictures to think about other problems that arise in the book?

- How do we work the materials part of it? Do manipulatives and white boards work for K/1 while a story is being read or is it too much distraction?

- What follow-up activities, maybe writing, could we think about after the book is read?

Unfortunately, our time together ended there. On Tuesday, we meet again and the teachers are going to bring some new books for us to plan a lesson around! So excited!