This post has been sitting in my drafts just waiting to be written for weeks now, thank goodness for a vacation to get all caught up!

This lesson came about during the same Kindergarten planning session as the Both Addends Unknown (BAU) lesson. As the team and I talked about the dot images they had recently been using during number talks and the decomposition of number standard, we were curious how students would do with a context in which a number is broken down into more than two addends. We knew it wasn’t exactly matching the standard, however we were interested in seeing how the ideas that emerged were similar or different from the BAU problem.

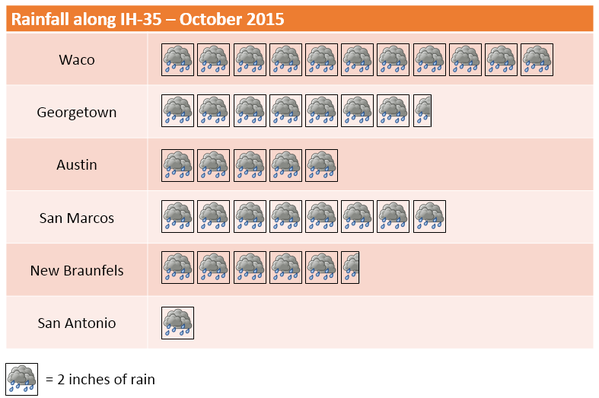

The first piece of our planning was developing a context so the students would have a visual of something moving from one place to another as the addends changed. For no better reason than the fact that Jodi, the classroom teacher, had counting bears, we decided upon polar bears as our context. We launched the problem with an image of 6 polar bears swimming at a zoo, all in the same pool. We asked the students what would happen if the zoo had six different pools for the bears to choose from? Could they all be in the same pool? Could they each be in a different pool? How many different ways could these 6 bears be arranged in the pools? The students did some talking about how they could swim together or by themselves.

I then showed them the muffin tin below and asked if this could be the pools for us to work with today since we didn’t have the actual bears or zoo with us. They counted and agreed it could be the pools since there were 6 spaces, but we had to also agree that it was “not big enough for the real bears.”

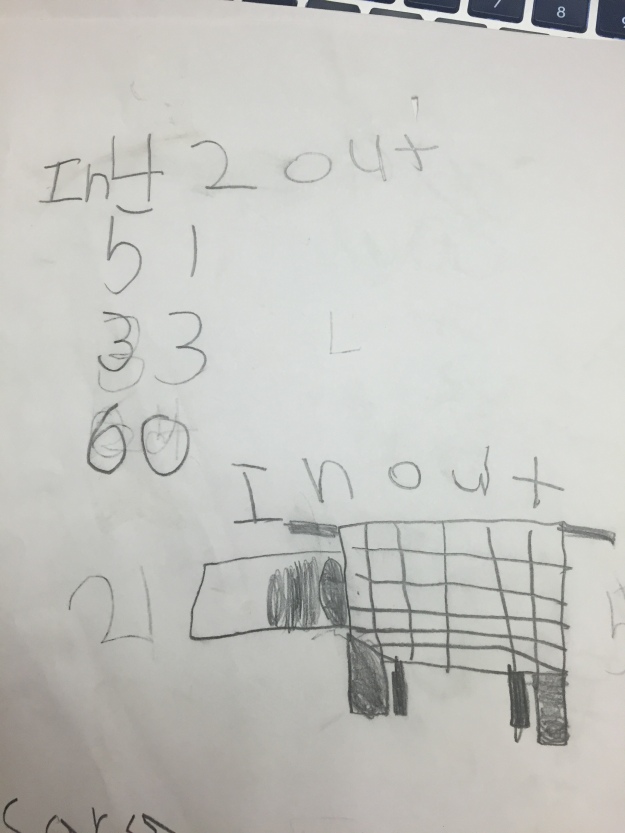

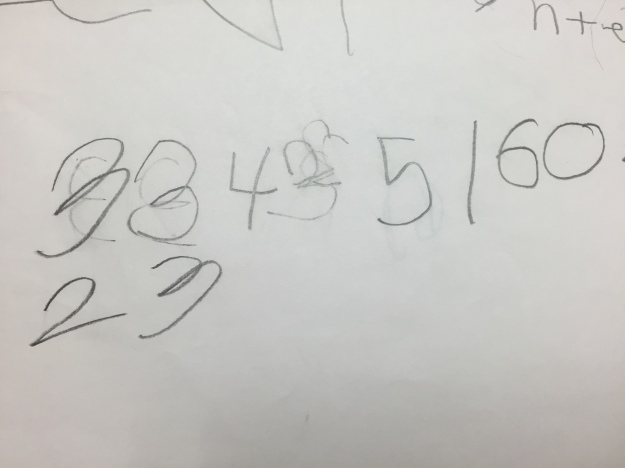

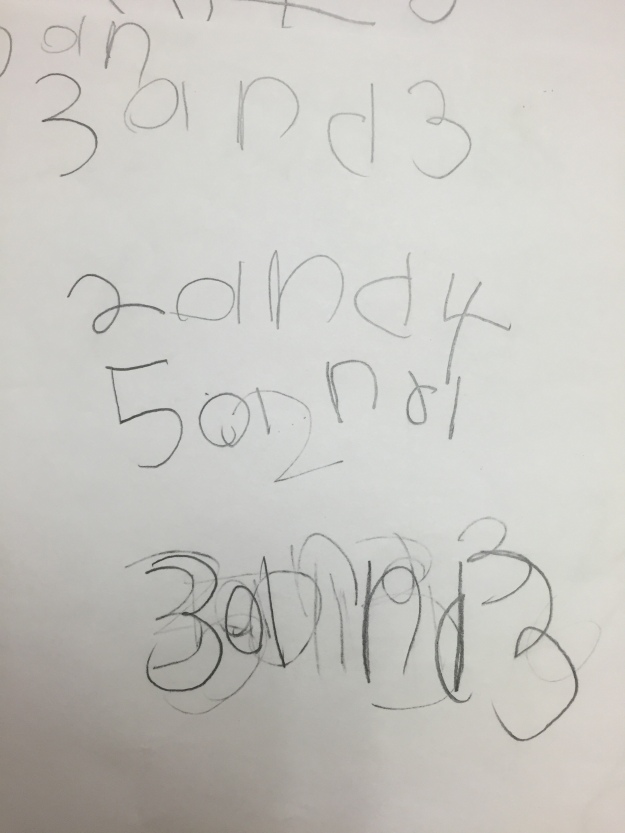

Jodi and I knew recording freely in a journal would have been a bit tricky without something to match the tin, so I printed the image below and we put a stack of them on each table for students to use. We did have a conversation on the carpet about recording, because our goal was for students to have multiple ways to decompose the group of 6 and we didn’t want time wasted drawing bears. I asked them how we could show the bears if we didn’t draw each one and dots and circles were the most agreed upon way.

I felt like this whole introduction took way too long. I don’t know how to make it quicker, but I would have loved to have had more time at the end of the lesson connecting the representations than in the launch. Perhaps just giving them 6 bears and asking how they could be in the tin, recording it on the board, asking them to change it, recording those, and then comparing?

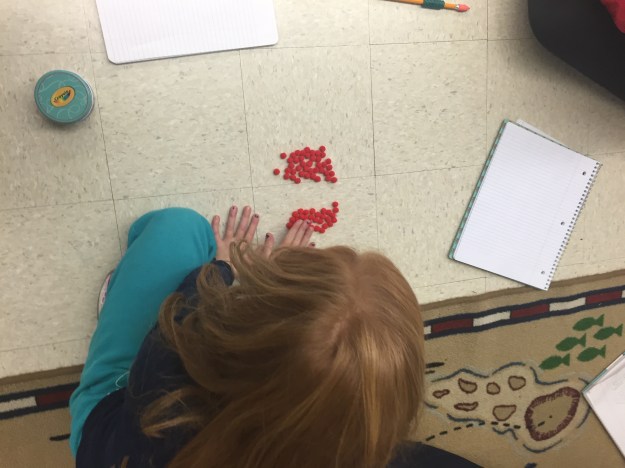

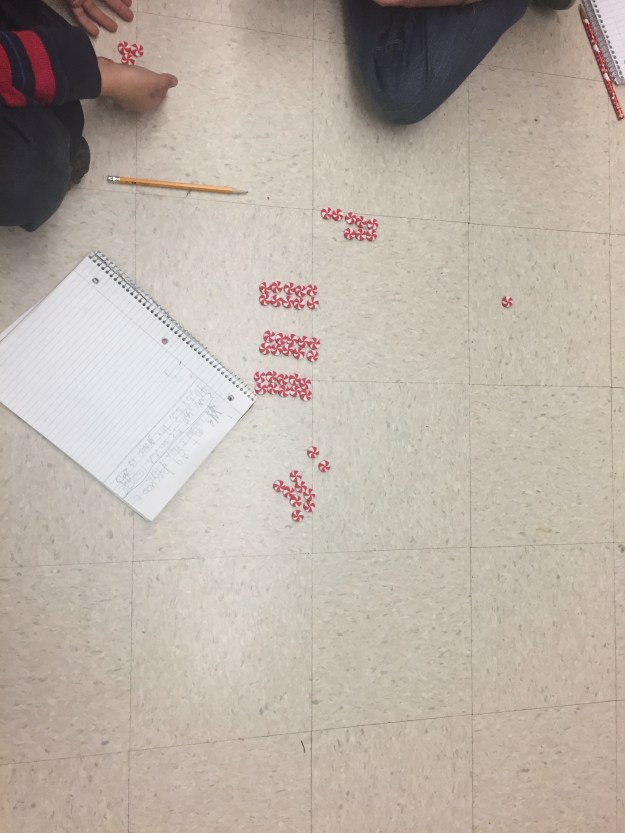

From there, we set them off with a partner, 6 bears and a muffin tin. I was so impressed by the way they worked together. In so many groups, one student moved the bears in the tin while the other recorded and then they switched. As they got the hang of moving the bears around, a lot of them began to look like they were on a race, cranking out a ton of different recordings. We did not have to give them more than 10-15 minutes before they had at least six or more ways. We stopped them from working, asked them to put their papers out on the table in front of them, and talk to their partner about ones that seemed the same and ones that seemed different.

As they spread them out on their tables and chatted, I saw and heard SO much possibility but not enough time. So many patterns, so many interesting ways of composing and decomposing groups, and so much commutativity. However, they were leaving for recess soon and we wanted to wrap it up with a whole class notice/wonder before they left.

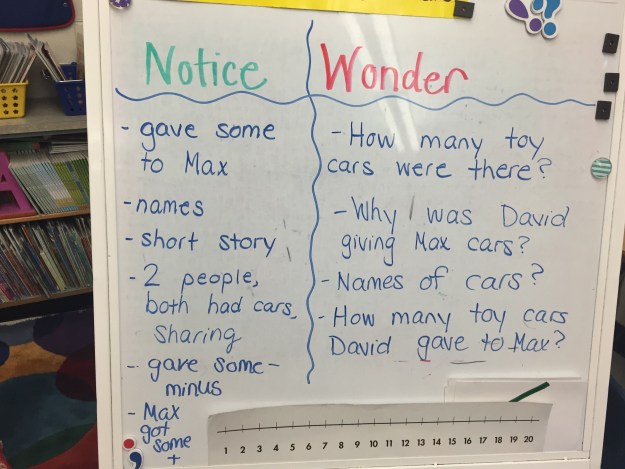

I strategically chose sets like the ones in the pictures above and asked students what they noticed/wondered. This is the point where you could see a bit of the hour-long math class fatigue setting in. A lot of noticing of 6 total bears and patterns such as 2,1,2,1 and 2,2,1,1, however we did not hear any talk of how the bears regrouped. For example in the 1,1,1,1,1,1 and the 2,2,2, I was wondering if students may say the two ones each made a two or any type of movement like that. I wonder if I asked how they were the same or different if I would have gotten a different response? Not sure.

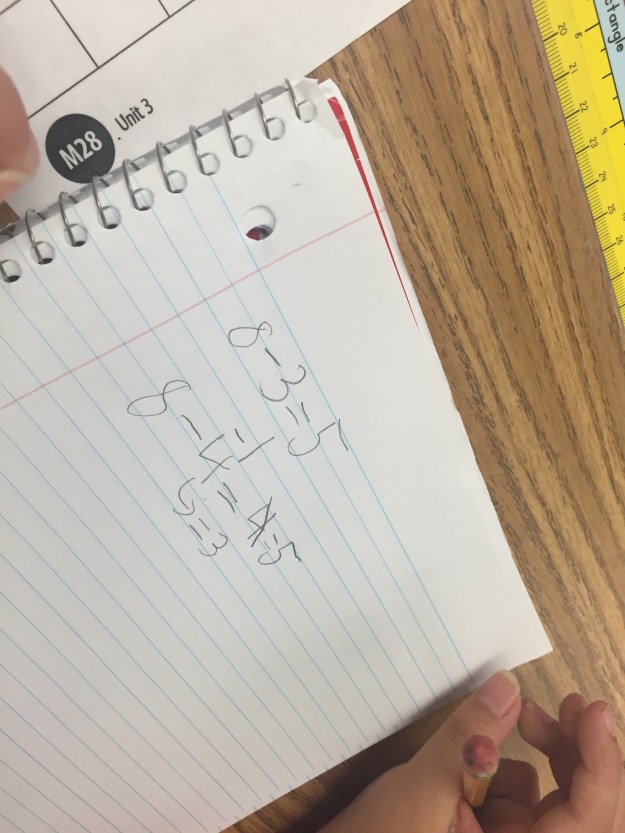

Jodi and I chatted after the class and agreed we wanted to revisit this lesson. We wanted to revisit because we did not get to writing equations for each picture, as we had planned. We were curious to see what they would do with that and if any other similarities and/or differences would arise. We also thought this could be a great activity for a math center, but we are just not sure what angle to take with it yet. Could it be about arranging them three ways and then comparing? Could it be practice at writing equations for their model? Could it be eventually knowing the combinations without manipulating the bears? Could it possibly be a mix of all of this? I am not sure…I am learning everyday in Kindergarten!