If you have seen my recent Twitter feed and blog posts, you can probably tell I am currently obsessed with Counting Collections! Because of this obsession, during our recent K-2 Learning Lab I made it the focus of our conversation. This was our first chance to talk across grade levels during a Lab and to hear the variation in ways we could incorporate counting in each was so interesting! Based on this lab, yesterday, I had the chance to participate in both a 2nd grade and Kindergarten counting collection activity and while there were so many similarities, I left each thinking about two very different ideas!

2nd Grade: Naming A Leftover

Based on our Learning Lab discussions three 2nd grade teachers had the amazing idea to combine their classes for a counting activity. While it was a great way to give students the opportunity to work with students from other classrooms, it also offered the teachers a chance to observe and talk to one another about what they were seeing while the activity was in progress. I was so excited when they sent me their idea and invitation to join in on the fun! I have never seen so much math in an elementary gymnasium before!

There was a lot of the anticipated counting by 2’s, 5’s, 10’s and a bit of sorting:

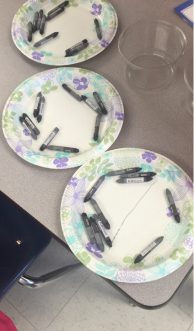

And while this is so interesting to see students begin to combine their groups to make it easier to count in the end, there were three groups counting base 10 rods that particularly caught my attention:

1st Group (who I missed taking a picture of): Counted each rod as 1 and put them in groups of 10.

2nd Group: Counted each rod as 10 because of the 10 cube markings, making the small cube equal to 1. They had a nice mix of 20’s in their containers!

3rd Group: Counted each rod as 10 but had a mix of rods, small cubes and some larger blocks. It was so neat to see them adjust the way they counted based on size…the rod=10, small cube=1 and the large block=5 (because they said it looked like it would be half a rod if they broke it up). After this beginning picture, they arranged the 10 rods to make groups of 100.

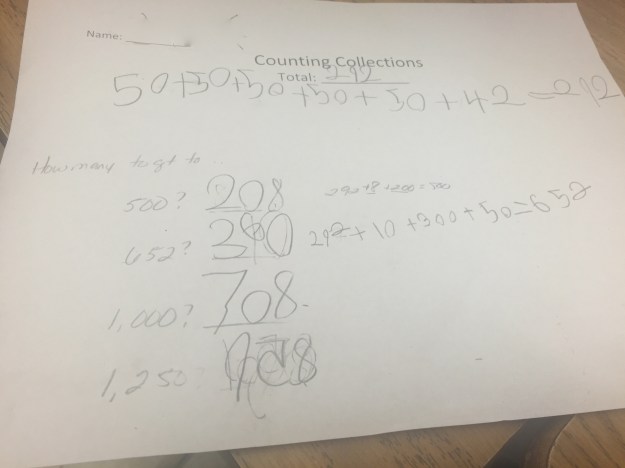

The second and third group ended up with a final count and recorded their thinking, however group 1 could not wrap it up so neatly. When they finished counting they had 141 rods but one small cube left over. Since they were counting each rod as 1, instead of 10, they were left trying to figure out how to name that leftover part. When I asked the group what they were thinking, one boy said, “It is kind of like half but smaller.” I asked him how many he would need for half of the rod and he examined the rod and said 5. I have to admit, I wasn’t sure where to go with this knowing their exposure to fractions is limited to half and fourths at this point. So, I asked him, “How much we do have of one rod” and he said 1. I followed with, “Of how many?” and he answered, “Ten. So we have 141 and 1 out of 10?” Thankfully it was approaching time to clean up so I could think more about this one. I feel like I left that idea hanging out there and would love to bring it back to the whole class to think about, but I am still wondering, what question would have been good there? How would you structure this share out so this idea of how we name 1 is important and impacts our count? How do we name this leftover piece and why didn’t a group counting the same thing not have that problem? Also, I think it will important for these students to think about the question they could ask that their count would answer…For example, how many objects do you have – would that be accurate for the group who counted each rod as 10?

Kindergarten: Why Ten Frames?

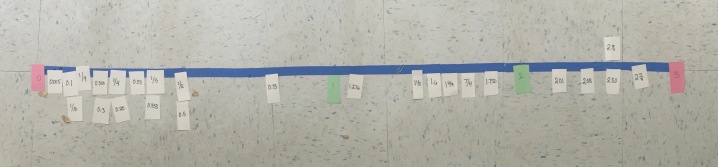

Every time I am in Kindergarten I leave with so many things to think about! In this case I left the activity thinking about Ten Frames. I am a huge fan of ten frames, so this is not about do we use them or do we not, but more about….Why do we use them? How do we use them? What is their purpose? What understandings come from their use? What misunderstandings or misconceptions can be derived from their use? and Where do these misunderstanding rear their ugly head later?

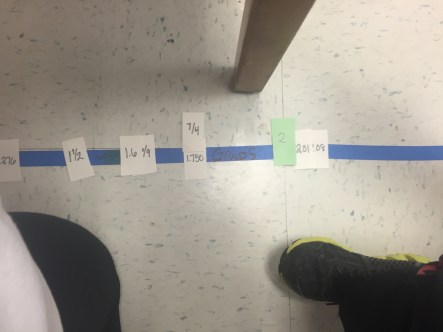

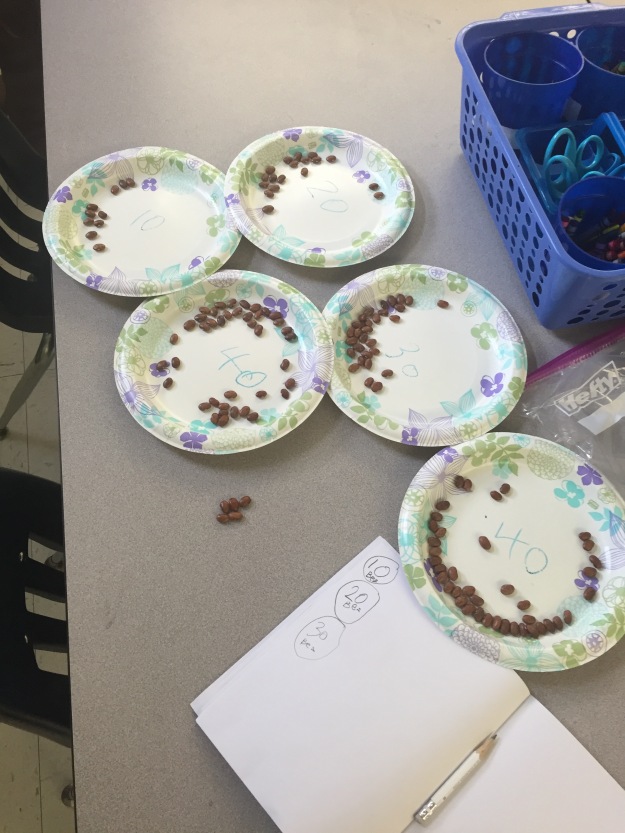

To start the lesson, groups of students were given a set to count. With a table of tools available to help them organize their count, ten frames were by far the most popular choice. However, not having enough (purposefully) for everyone’s set pushed them to think of other means… which ended up looking like they were on a ten frame as well!

As the teachers and I went around and chatted with groups, we heard and saw students successfully counting by 10’s (on the frames or look-alike frames) and then ones. This is what we hope happens as students work with the ten frames, right? They see that group of 10 made up of 10 ones and then can unitize that to 1 group. It reminds me of Cathy Fosnot’s comment via Marilyn Burns on Joe’s post, which I had huge reflection on after this lesson too!

I was feeling great about the use of ten frames until a first grade teacher and I were listening to one group count their set. I wish I snagged a pic, but I was so stuck trying to figure out what to ask the girls, that I didn’t even think about it. They had arranged 4o counters on 4 ten frames and had one left over, sitting on the table, no ten frame. We asked how she counted and she said, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50…the 1 leftover was counted as a 10. I immediately thought of Joe’s post. Not knowing exactly what to do next, I tried out some things…

- I picked up the one and asked her how many this was, “One” and then pointed and asked how much was on the ten frame, “Ten.” Ok, so can you count for me one more time? Same response.

- I filled an extra ten frame pushed it next to her 4 other full ones and asked her to count: 10, 20, 30, 40, 50. I removed 9, saying “I am going to take some off now,” leaving the one on the ten frame and asked her to count again. Same response.

- I asked her to count by 1’s and she arrived at 41. So I asked if it could be 41 and 50 at the same time. She was thinking about it for a minute but stuck with “that is what I got when I counted.”

- Then I became curious if she had a reason for using the ten frame, I asked. She said it was to put her things on so I began wondering about the usefulness of the 10 frames for her. Was is something, as an object, that represents 10 to her but not able to think about the 10 things that make it up?

I left that class thinking about how complex unitizing is. We hope students are able to count 10 things, know those 10 things are still there even when we start calling a unit, 1 ten, and then combine those units but still know there are 10 in each one of them. WOW, that is a lot! However, they can easily appear successful in counting by 10’s, which is one of the many reasons Counting Collections are so powerful. They bring to light the misunderstandings or missing pieces in students’ thinking.

I then start to think of recent conversations I have had with 4th grade teachers about students who are struggling with multiplying a number by multiples of ten and wonder if this is where we can “catch” those misunderstandings and confusions before they compound?

What to do next with this class? Erin, the teacher, and I quickly discussed this as she was busy transitioning between classes. We were thinking about displaying an amount, lets say 23, with two full ten frames with 3 extra. Say to the class, “Here are two sets, do they look the same? How can you tell? Two groups counted this amount two different ways. One group counted it 10, 20, 21, 22, 23 and the other group counted it 10, 20, 30, 40, 50. Can it be both? If so, how? If not, which one is it?”

Would love any other thoughts. I am heading back to re-read all of the comments on Joe’s post to gain more insight, but I would love your thoughts too!