I have never been more intrigued with using Cuisenaire rods in the classroom until I started reading Simon’s blog! I admit, I have read and watched his work from afar…not knowing really where to start with them and was afraid to just jump into another teacher’s classroom and say, “Hey let me try out something!” when I really didn’t know what that something may be. However, after Kassia reached out to Simon on Twitter asking how to get started with Cuisenaire rods and Simon wrote a great blog response, I was inspired to just jump right in!

I am a bit of an over-planner, so not having a really focused goal for a math lesson makes me a bit anxious. I am fairly certain I could anticipate what 4th and 5th graders would notice and wonder about the Cuisenaire rods because of my experience in that grade band, however I wanted to see what the younger students would do, so I ventured into a Kindergarten and 3rd grade classroom with a really loose plan.

Kindergarten (45 minutes)

Warm-up: Let’s notice and wonder!

- Dump out the bags of Cuisenaire rods in the middle of each table of 4 students.

- Tell them not to touch them for the first round.

- Ask what they notice and wonder and collect responses.

Things they noticed:

- White ones looked like ice cubes.

- Orange ones are rectangles.

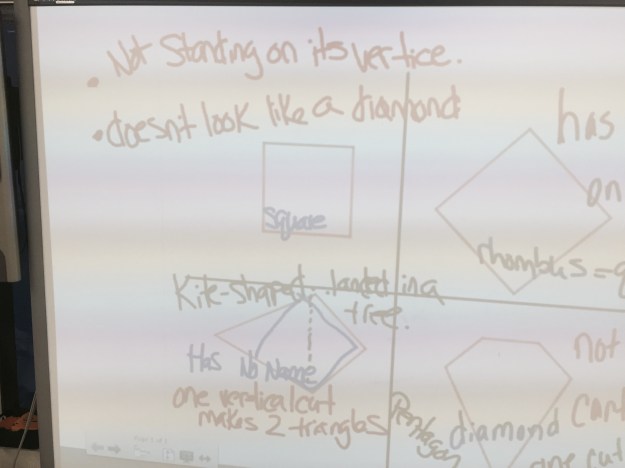

- End of blue one is a diamond (another student said rhombus)

- Different colors (green, white, orange..)

- They can build things (which is why we did no touching the first round:)

- Orange is the longest.

- They are different sizes.

- We can sort them by colors.

- We can sort them by size.

Things they wondered:

- What do they feel like?

- What can we make with them?

Activity 1: Let’s Sort!

- Tell the students to sort them by size or color. (they quickly realized it was the same thing)

- Discuss their sort/organization and check out how other tables sorted.

I was surprised to see not many sorted them into piles because that is normally how they sort things. I am wondering if the incremental size difference between each rods made them do more of a progression of size than sort into piles? Some groups worked together while others like making their own set with one of each color (and size) and keep making more of those!

Activity 2: Let’s Make an Orange!

Since a lot of students kept mentioning that the orange was the longest, I decided to see if they could build some trains (as Simon calls them) that made an orange.

My time was running out, but it left my mind reeling of where I wanted to go next! My inclination is to ask them if they could assign numbers to some of the rods or if they could build some trains the same length as the different colors? I would love to hear which piece is their favorite piece because a lot of them found the smallest cube really helpful when building the orange.

3rd Grade (60 minutes)

Warm-up: Let’s notice and wonder!

Things they noticed:

- Groups were the same color and length.

- Blue and white is the same length as the orange rod.

- Kind of like adding.

- White is 1 cm.

- Go up by one white cube every time.

- Odd + even numbers

- 2 yellows + anything will be bigger than 0.

- 1 white + 1 green = 1 magenta

Things they wondered:

- Is red 1 inch?

- How long are the rods altogether? (Prediction of 26 or 27 in wide)

- Is orange 4 1/2 or 5 inches?

- Why doesn’t it keep going to bigger than orange?

Activity 1: Let’s build some equivalents!

I found 3rd graders love to stand them up more than Kindergarteners:)

Activity 2: Let’s assign some values!

After they built a bunch, I asked them to assign a value to each color that made sense to them…this was by far my favorite part – probably because it was getting more into my comfort zone!

Again, time was running out, but next steps I am thinking…

- What patterns and relationships do you see in the table?

- What columns have something in common? Which ones don’t have anything in common? Why?

- What if I told you orange was 1? What are the others?

- What if orange was 2? What happens then?

Thank you so much Simon for all of inspiration and Kassia for the push into the classroom with these! Reflecting, I was much more structured than Simon and Kassia, but I look forward to a bit more play with these as the year goes on! I look forward to so much more play with the Cuisenaire rods and continuing Cuisenaire Around Ahe World!