Whenever it snows, it feels so cozy inside that I just have the urge to read and write. And nothing inspires me more to write than student thinking. And there is no better place to see student thinking than in math journals!

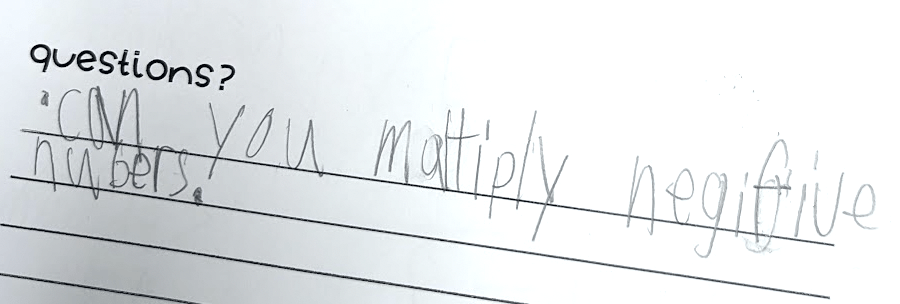

When I was a classroom teacher, my fifth graders wrote in their math journals almost every single day. Sometimes they used them before a lesson to record estimates or predictions. Other times they wrote during class to capture their ideas as they worked through a problem. Often, they ended the lesson with a short prompt. No matter how the journals were used, they were always a safe, ungraded space for students to put their thinking on paper. And no matter the prompt, I learned something new every day about my students’ thinking simply by reading their entries.

Later, as a math specialist, I had the opportunity to see student writing in math classrooms across many grade levels, and it was so fascinating. I could see where it all begins in Kindergarten, when students are representing ideas with drawings and numbers, and how that thinking evolves through fifth grade as students’ written reasoning becomes lengthier and the prompts become more metacognitive. In every lesson I planned with teachers, we would build in a writing prompt. Those student responses, would always give us a new window into each student’s thinking.

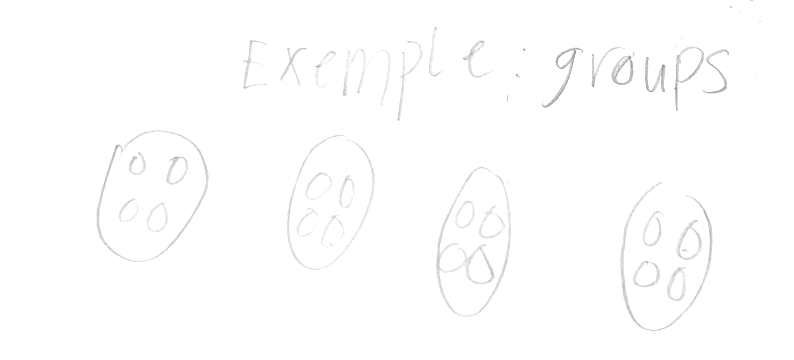

For example, when I planned a lesson on arrays with a third-grade team, we intentionally designed an exit prompt that went beyond a simple right-or-wrong answer. The lesson began with a Dot Image, and students spent the rest of the time building arrays and writing equations to represent them. At the end of the lesson, we returned to one of the dot images from the launch. Instead of asking students to write an equation, we asked them to choose two mathematical expressions that had been shared during the Dot Image discussion and explain how those expressions were the equivalent using the image.

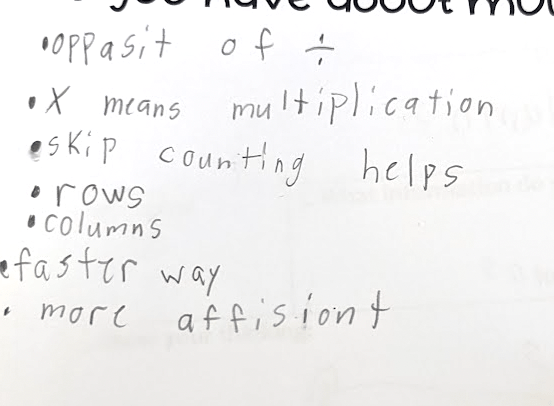

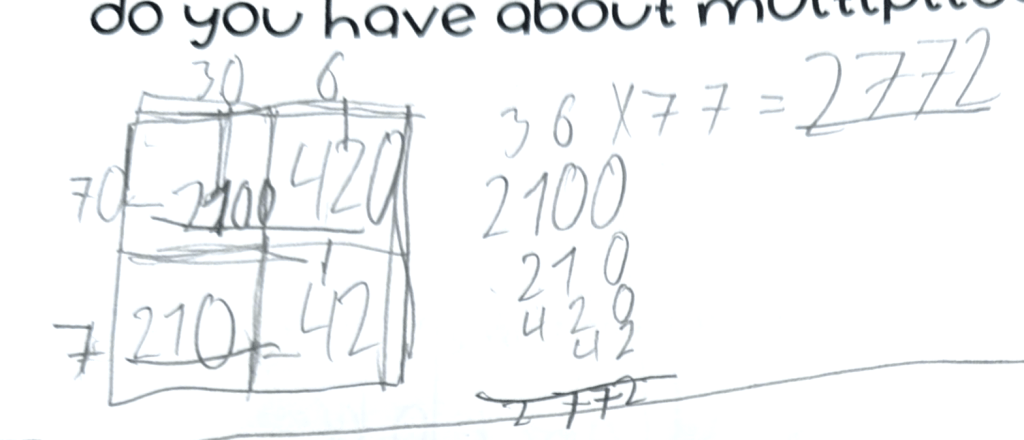

When we later looked through the student journal responses, they became the anchor for our reflective conversation. Each journal entry revealed something a little different: how students were making sense of multiplication, the connections they were noticing, and where their thinking was still emerging.

Math journals don’t just show us what students can do; they offer a window into how students are thinking. Let’s take a closer look at some of that student work based on broader mathematical understandings.

The Commutative Property

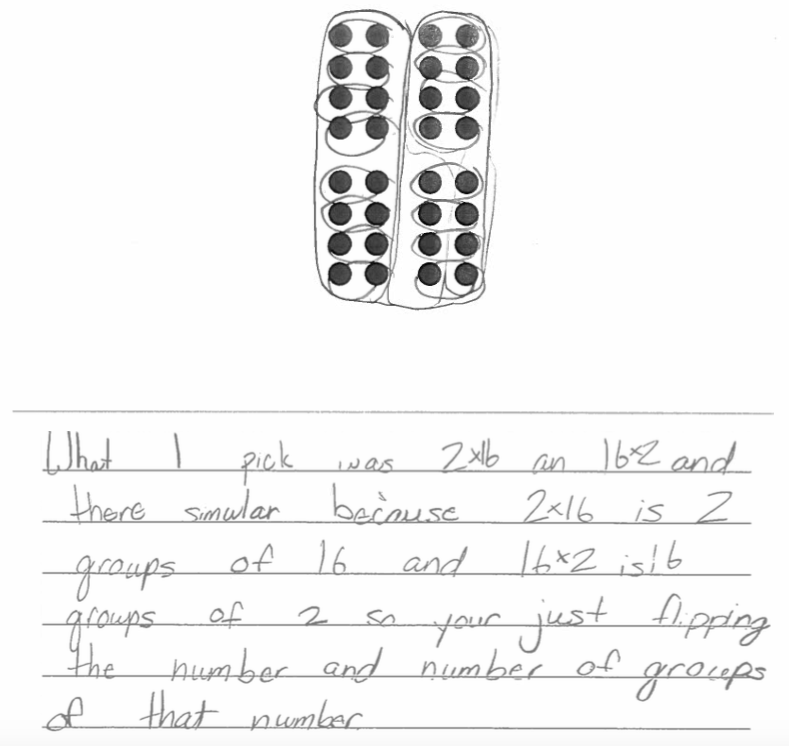

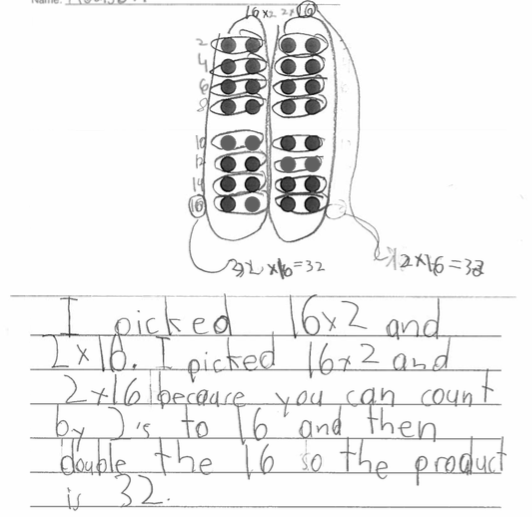

The majority of students chose two expressions demonstrating the commutative property of multiplication. Often students see that you can change the order of the numbers in a multiplication problem and the product remains the same, however in the journal entries, we were able to see student understanding of this property in a representation.

16 x 2 = 2 x 16

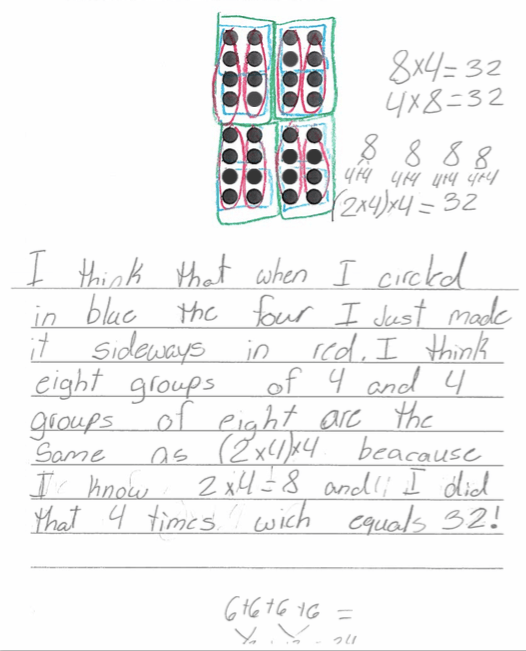

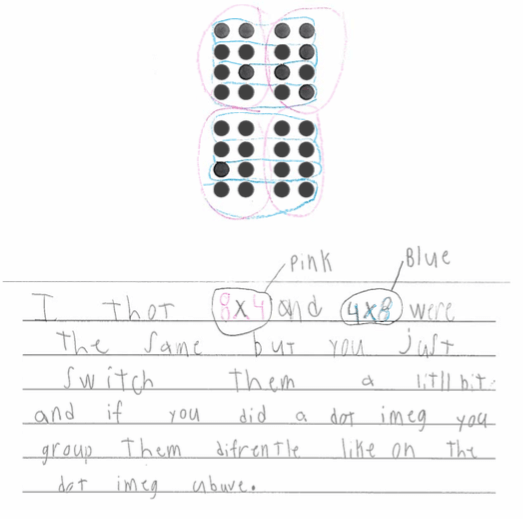

8 x 4 = 4 x 8

16 x 2 = 2 x 16 and 4 x 8 = 8 x 4

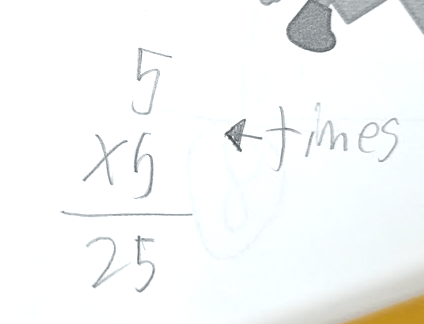

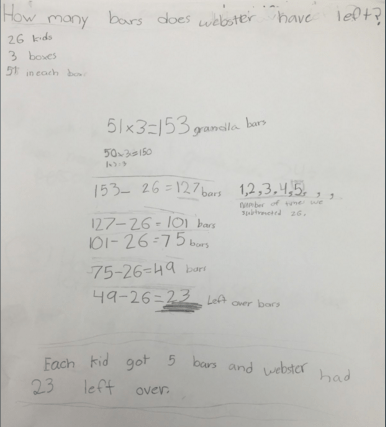

Changing the Number of Groups and Number in Each Group

A few students noticed that when they changed the number of groups and the number of dots in each group, the product remained the same. While these students are not yet articulating how the groups are changing, this work provides a great opportunity to plan future conversations around this idea.

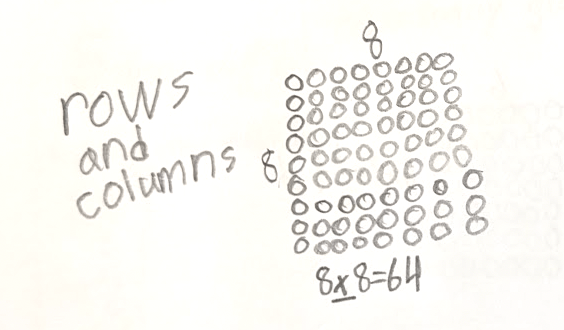

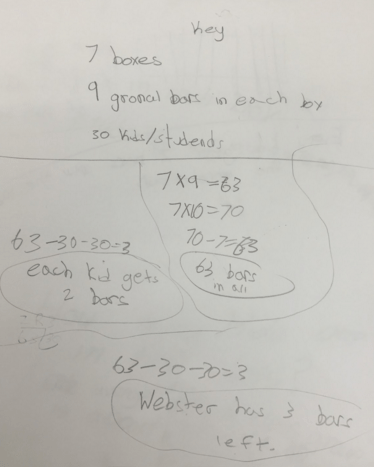

Rearranging the Groups

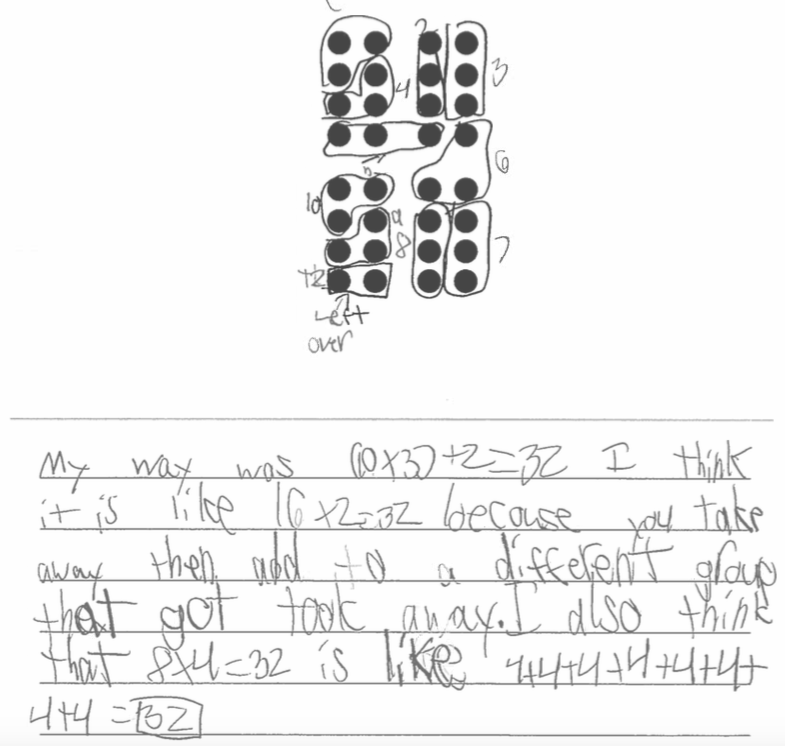

This response is very similar to the previous responses, however this student is beginning to articulate how the groups are changing. Instead of having 10 groups of 3, the student explains he took some dots away and added them to another group to make 16 groups of 2.

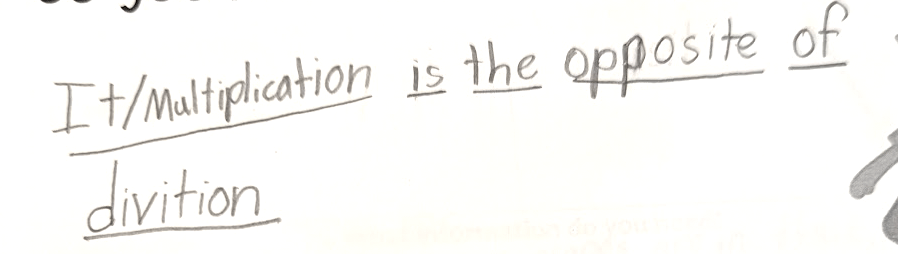

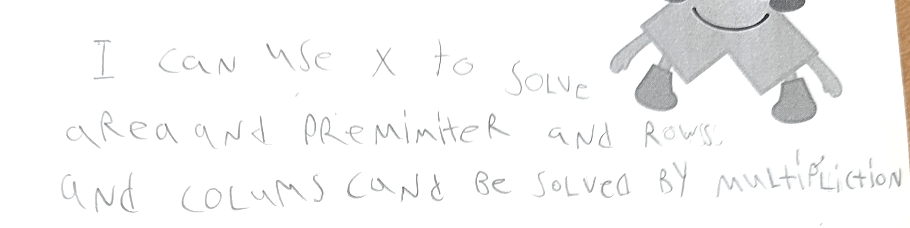

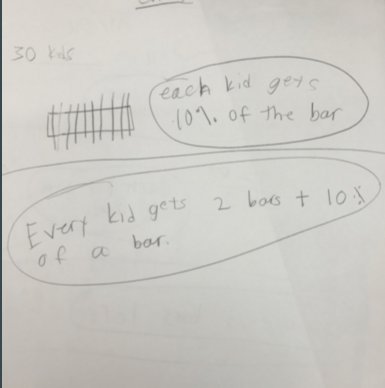

Relating Operations

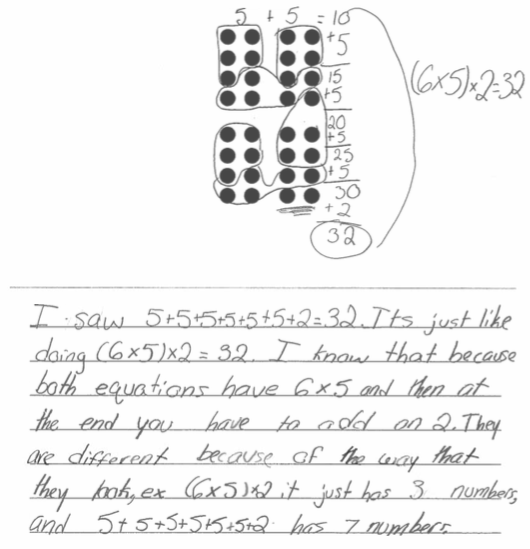

Some students related expressions based on what they understand about the operations and were able to represent these understandings in the dot image.

While the team and I heard and observed so much interesting student thinking during the Dot Image discussion itself, the journal prompt allowed us to look more closely at each student’s understanding and see the connections they were making. It served as a important formative assessment, one that extended beyond what we could learn through discussion alone.

Math journals have transformed the way I listen to students’ thinking. I love seeing math journaling used across grade levels, from students who are just beginning to represent their ideas to those who are refining written explanations. Journals give students who may not feel comfortable sharing aloud a space for their voices to be heard, while giving teachers invaluable insight into how students are making sense of the mathematics. I encourage all math teachers to incorporate math journals into their classrooms—not just to see how students arrived at an answer, but to uncover the connections, understandings, and confusions that shape their learning. That insight truly informed every planning decision I made in my classroom and deepened my understanding of the not only the mathematics, but how students build mathematical understanding.

Now, off to make some more coffee, grab a good book, and then follow up with some Fortnite or Zelda gaming time:) Happy snowy Sunday all!