The answer is 1/2. What is the question?

Pause for a moment to think about how you would respond to this prompt. After you have a question in mind, reflect on the thinking you did to come up with that question. What topics did you think about? Did they include mathematical representations, a real-world context, or calculations? Something else?

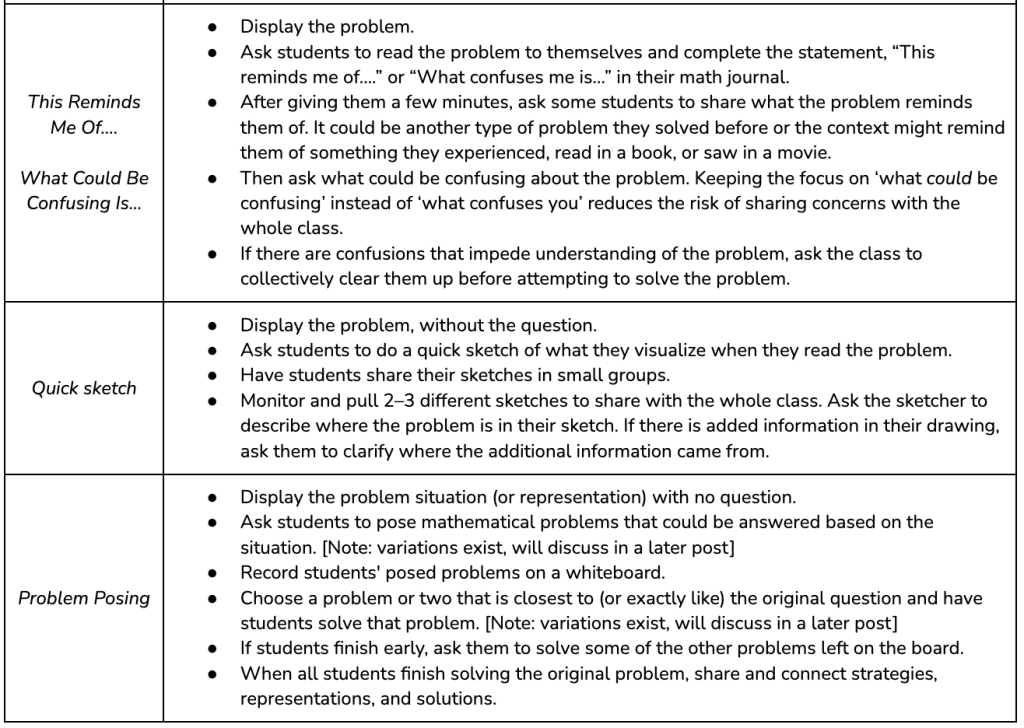

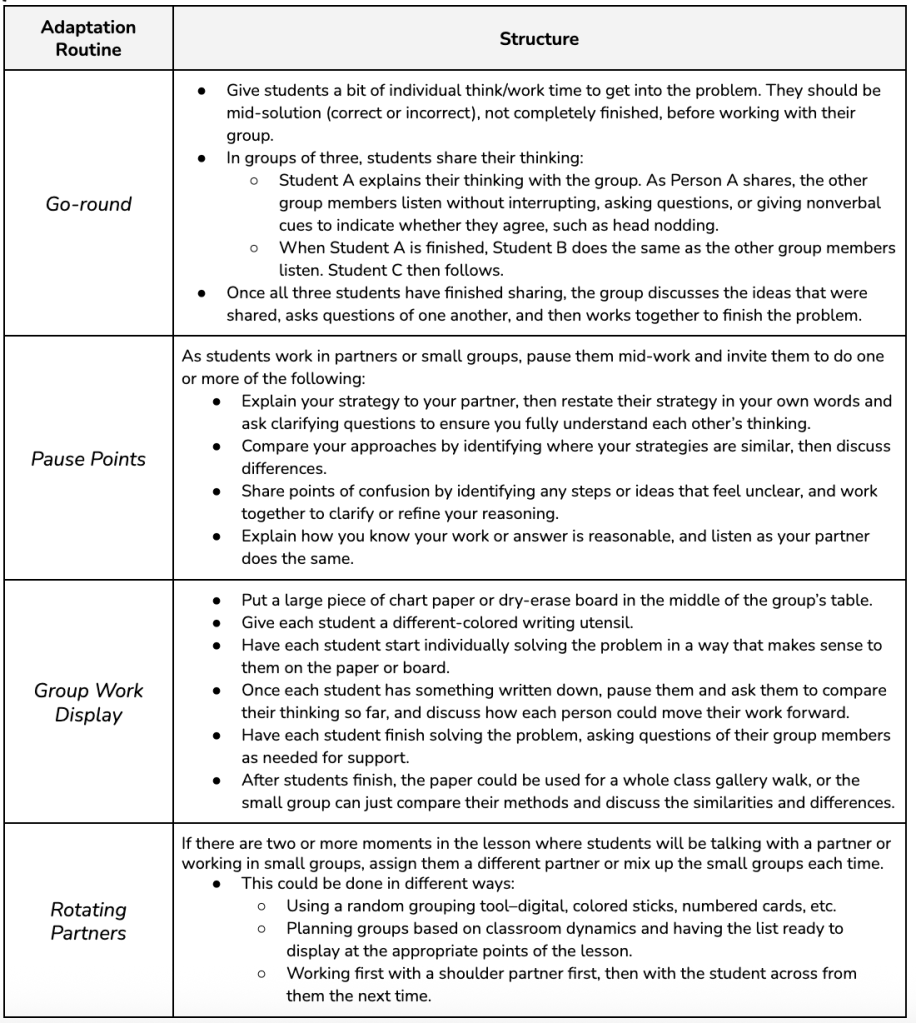

Last week, we had our second book study session for NCTM’s Teaching Mathematics Through Problem Solving K–8. The focus of the session were chapters four and five around instructional tasks and teaching signposts that support students in learning through problem solving. We wanted to open the session with a good math prompt as everyone was arriving, a prompt that gave them something interesting to think about as we waited a couple of minutes and also set the tone for the learning we were going to do together. Since the session was focused on instructional tasks, we wanted to begin with one that reflected what we value in classrooms—tasks that invite everyone in and elicit a wide array of student thinking.

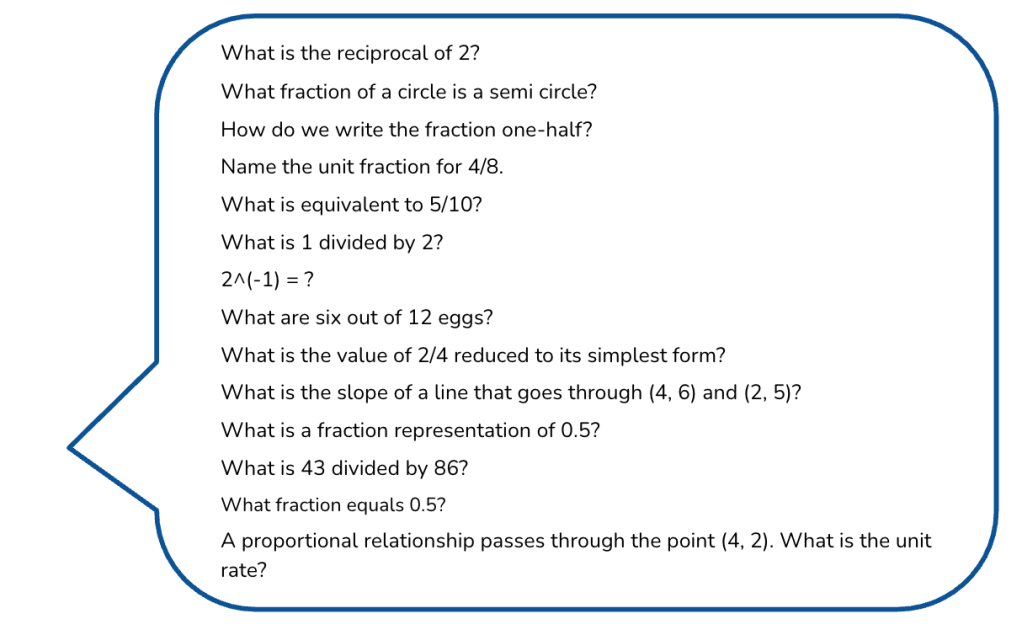

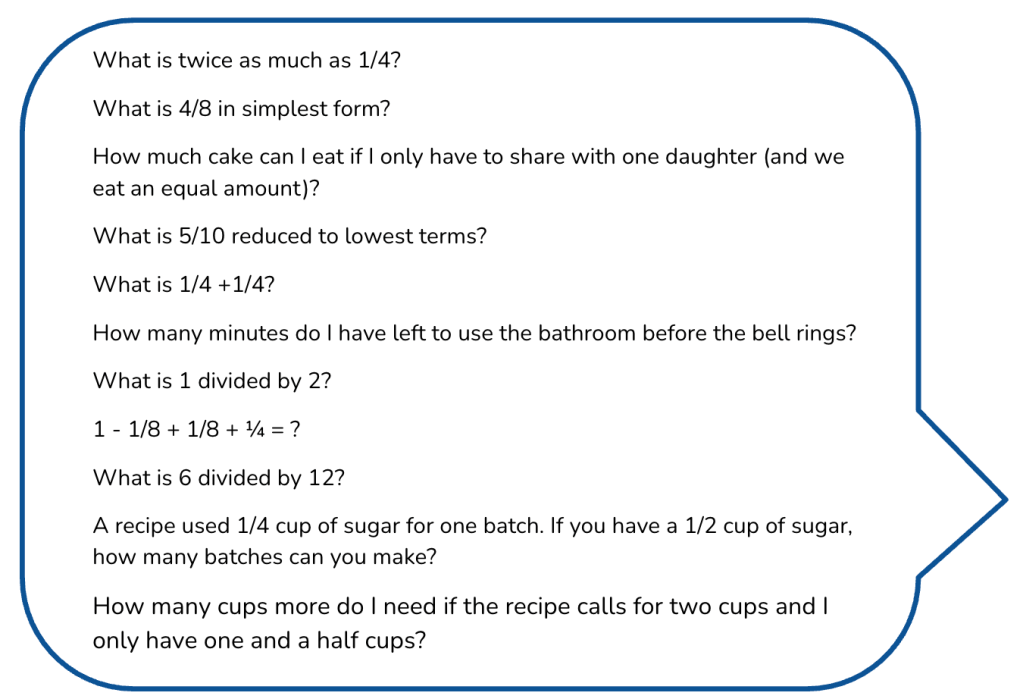

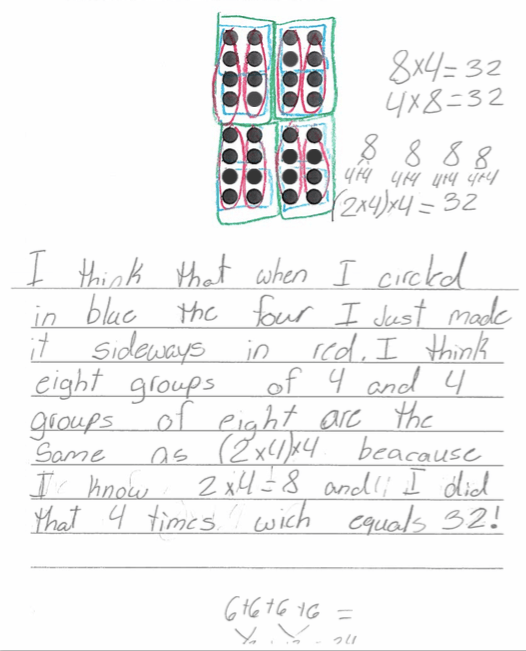

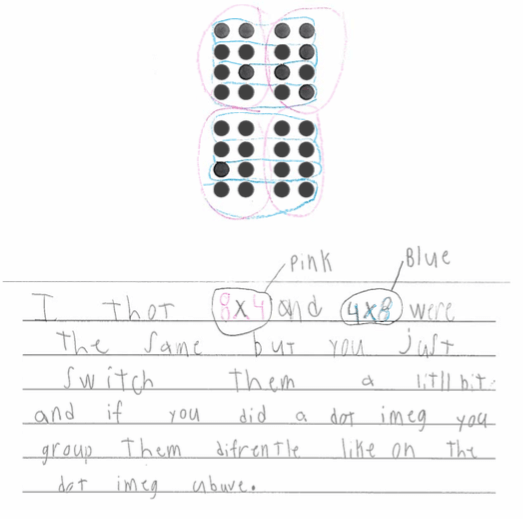

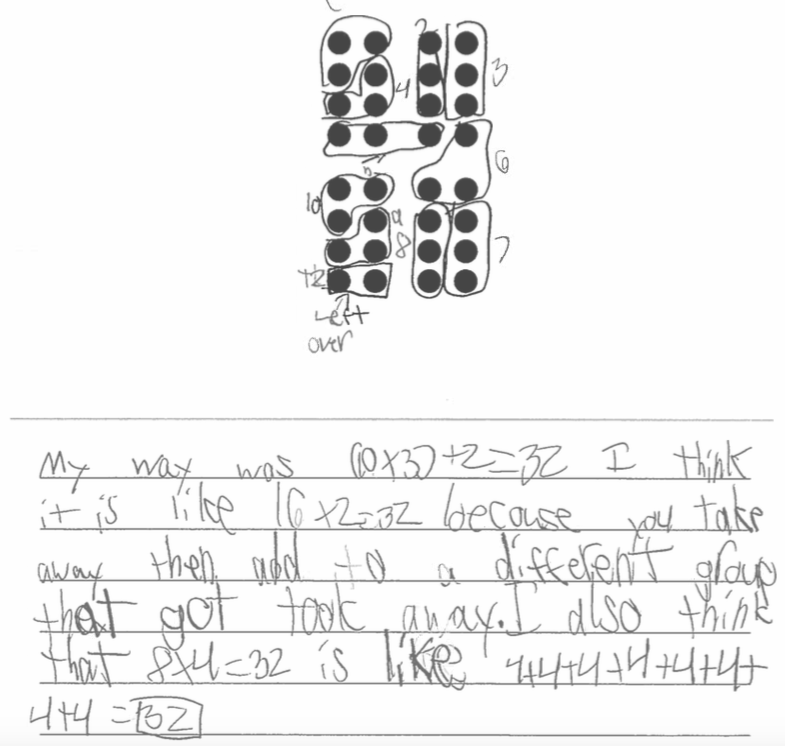

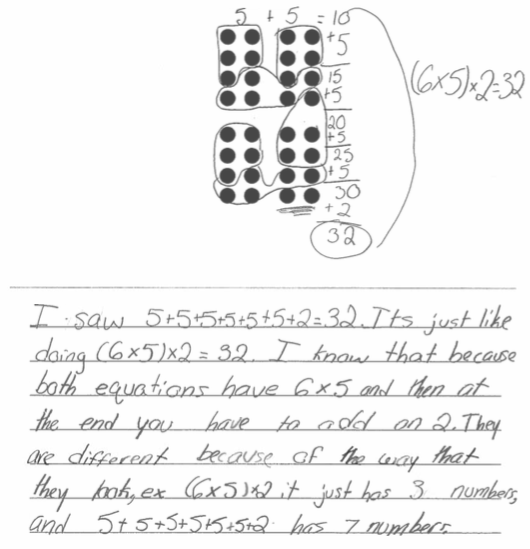

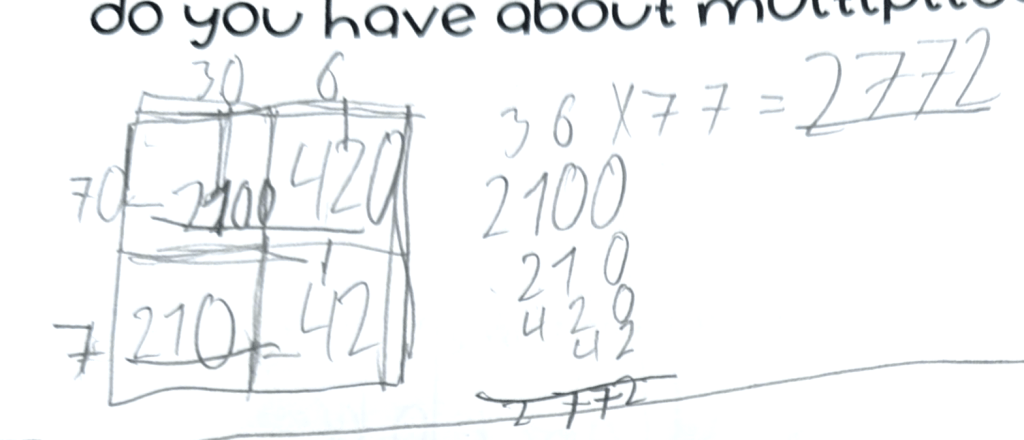

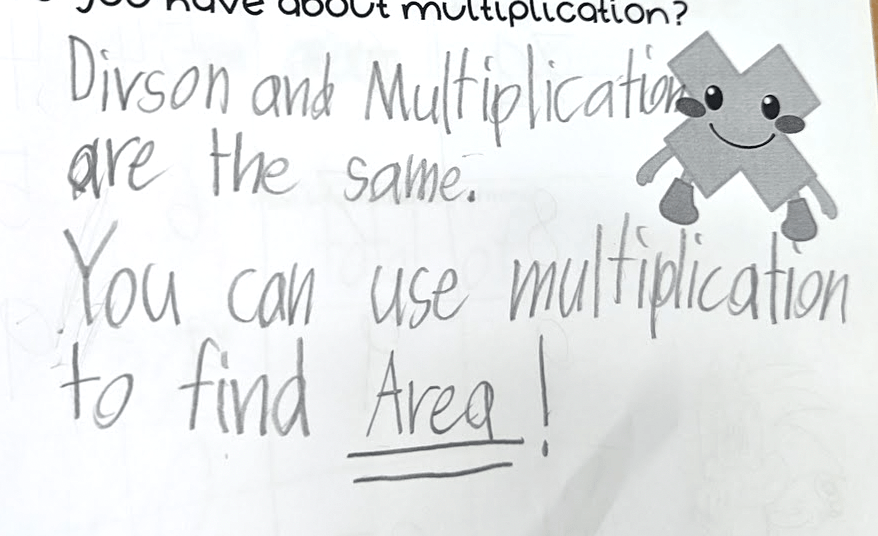

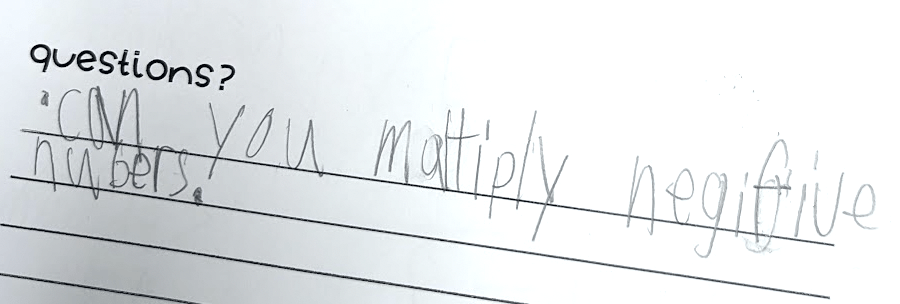

After a few seconds, the chat was buzzing. Here is a sampling of the amazing responses we got.

The variance in responses was so fun and got me thinking about when, where, and with whom a prompt like this might be especially powerful. I often use tasks like this to launch a unit, lesson, or activity so I can learn how students are thinking about the mathematical concept we are about to explore.

Launching a Lesson

A former colleague, Jenn, used this prompt to launch a 3rd‑grade lesson on comparing fractions. Using the task at this point in a lesson not only provided insight into students’ thinking, but also supported differentiation. Students who finished early had access to a bank of questions to evaluate, compare, and justify. Even better, those questions came directly from the students themselves.

Launching and Wrapping Up a Unit

Building on this idea, what might it look like to use a prompt like this not just to launch a lesson, but to bookend an entire curriculum unit?

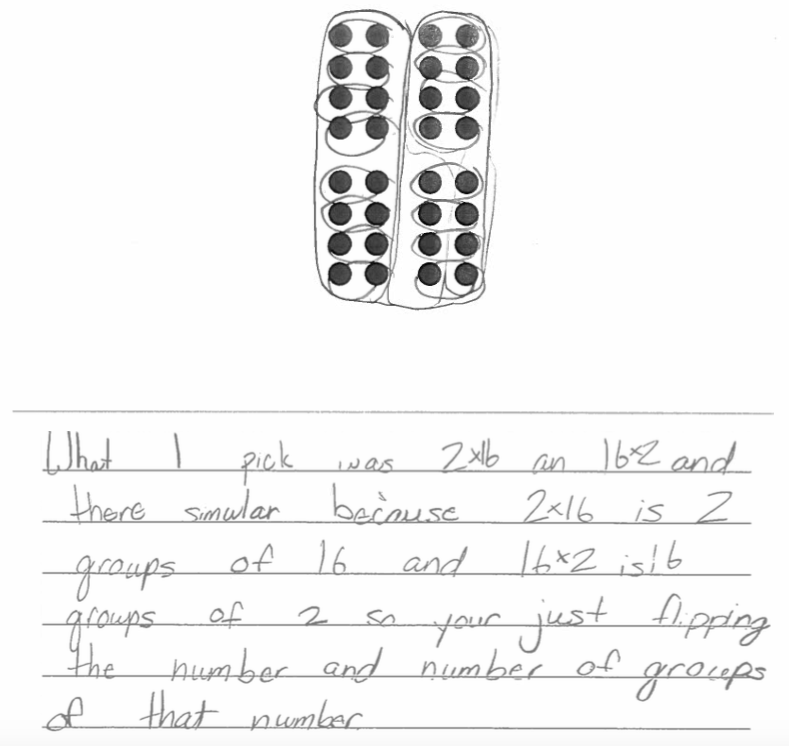

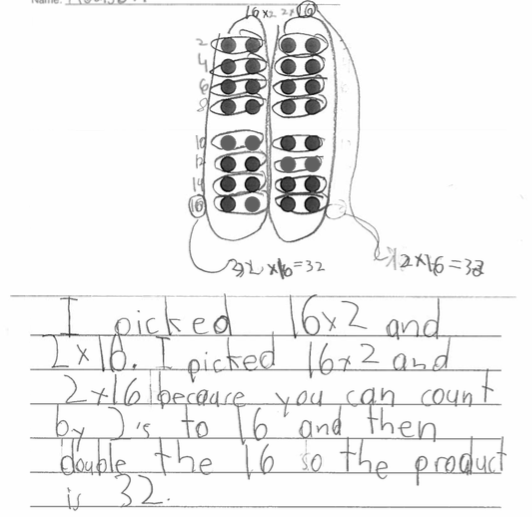

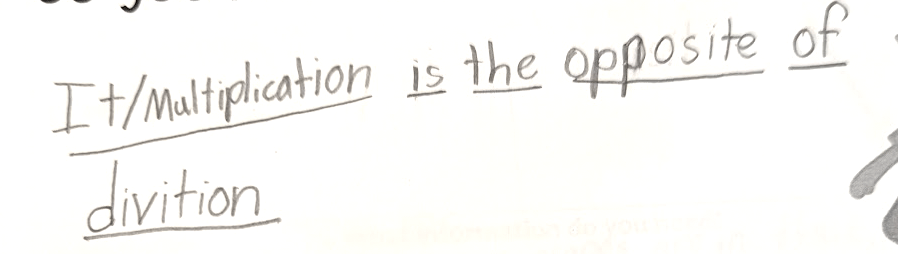

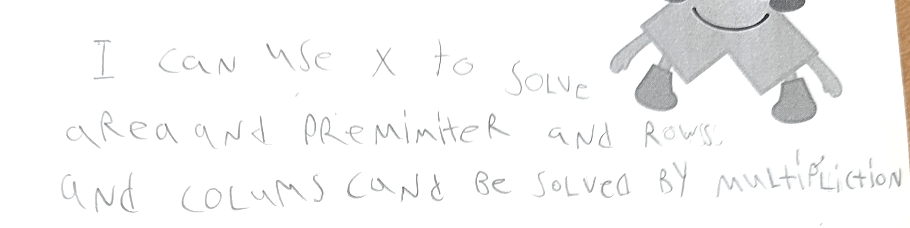

Before beginning a unit on fraction multiplication and division in 5th grade, we might pose the question, “The answer is 3/4. What is the question?” At the start of the unit, we would likely see fractional diagrams, addition expressions such as 1/4+1/4+1/4, or multiplication expressions like 3 ×1/4. All of these responses are incredibly valuable for eliciting what students currently understand about fractions.

By the end of the unit, however, students have developed new understandings about fraction multiplication and division. Revisiting the same prompt invites them to apply those new understandings in more sophisticated ways. Building on the original list of student‑generated questions at the end of the unit could serve as a powerful formative assessment and, just as importantly, a rich anchor chart that documents students’ learning over time.

Professional Learning

This idea also extends naturally to professional learning settings, particularly those that bring together educators across a wide range of grade levels. For example, in professional learning focused on the fraction learning progression, the list we generated at the beginning of our book study session would be invaluable.

A rough draft PD flow could look something like this:

- Pose the prompt and ask teachers to write their responses on index cards.

- In small groups, teachers share their questions and work together to align them to grade‑level standards.

- In larger groups, teachers collaborate to form a learning sequence, ordering the cards from the earliest fraction understandings to the latest.

- Teachers move into grade‑level groups to identify their curriculum unit in which they could use a prompt like this. For K–2 teachers, this would mean adjusting the prompt to use the words “one‑half” instead of a numerical representation (a variation I used in 1st grade).

- In grade‑level groups, teachers anticipate what students might say and plan how they will leverage student understanding and use student‑generated questions.

- The whole group shares ideas.

Reflection

Coming back to the book study, I found this book quote reflective of prompts like these:

Activities that provide access and extension are often referred to as having a low-floor and high-ceiling. Meaning, the problems invite all students to engage, while also providing space for deeper exploration. These types of tasks provide accessible entry points without lowering or limiting the cognitive demand of the mathematics. Mitch Resnick (2020) takes this idea even further with the concept of “wide walls,” which reminds us that learning shouldn’t just move from easy to hard, but should also give students space to explore ideas in different ways and directions.

Coming Up

If this prompt has you thinking about your own classroom or professional learning spaces, I’d love for you to continue the conversation with us. Join me on February 9 for a free webinar with Ashley Powell and Shawn Wigg as we explore instructional tasks that invite a wide range of thinking. We will relate the ideas in the NCTM book to practical applications of tasks in the classroom. Participants will receive an excerpt from the NCTM book, and we’ll raffle off a free digital copy at the end. Hope to see you there!