I am sure we have all seen it happen at one time or another in math class. We give a student a story problem to solve and after a quick skim, the student pulls the numbers from the problem, computes them, and writes down an answer.

If the answer is correct, we assume the student has a grasp of the concept. However, if it’s incorrect, we’re left with a laundry list of questions: Do they realize their answer doesn’t make sense? Did they not understand the context? Did they simply pull the numbers and operate to be finished or did they truly not know what to do with them? Most importantly, we ask ourselves, how can I help students make sense of what they are reading and think about the sensibility of their answer in the context of the problem?

If we’re lucky, we can identify a mathematical misconception and work with that. Oftentimes, though, the answer isn’t even reasonable. Then what do we do?

This scenario has me reflecting on the Common Core Standard of Mathematical Practice 1:

Mathematically proficient students start by explaining to themselves the meaning of a problem and looking for entry points to its solution. They analyze givens, constraints, relationships, and goals. They make conjectures about the form and meaning of the solution and plan a solution pathway rather than simply jumping into a solution attempt.

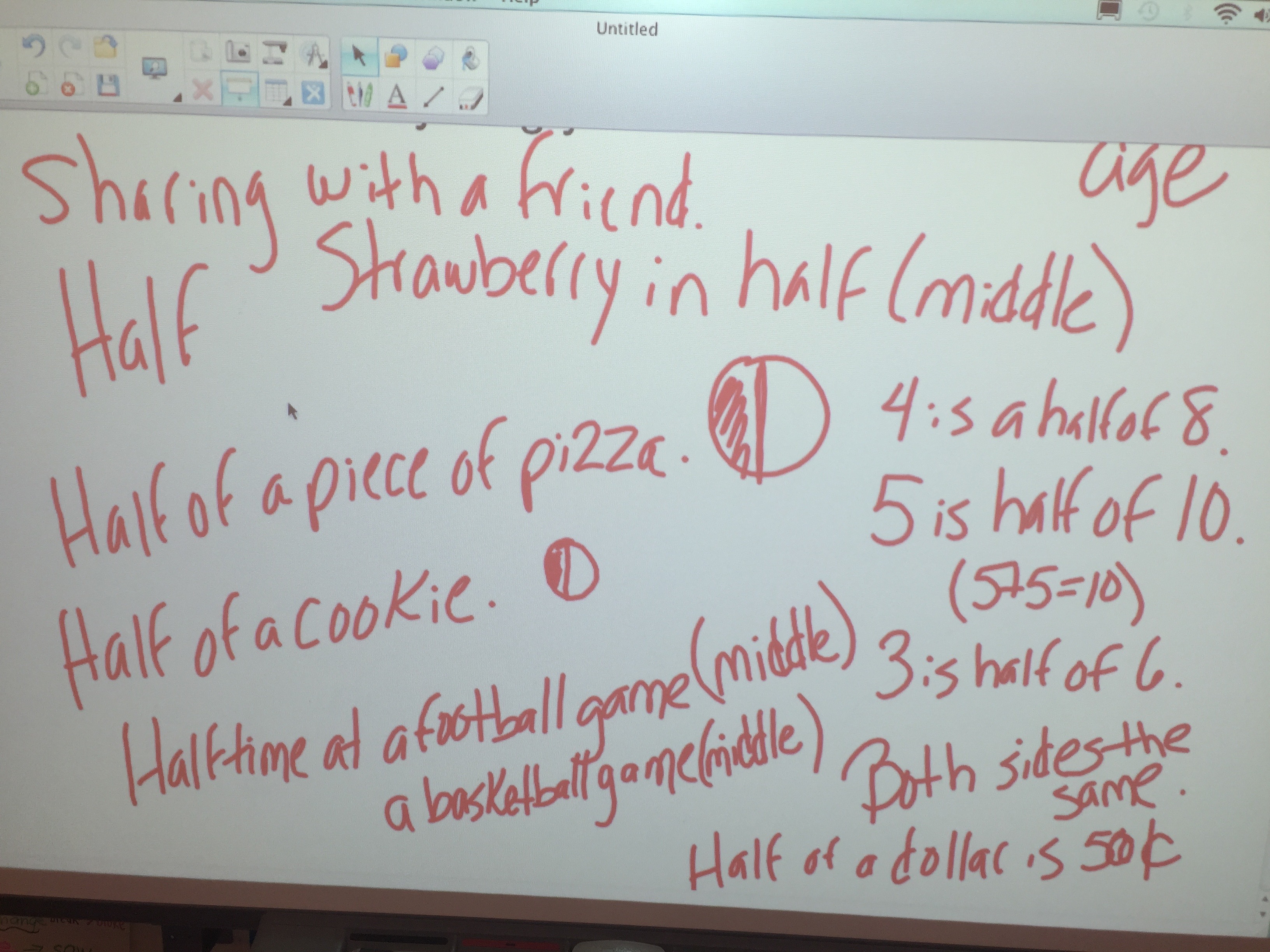

The best way I’ve found to help students make sense of what a problem is asking is, ironically, to take the question out altogether. Inspired by the wonderful folks at The Math Forum, I do a lot of noticing and wondering with students in this fashion. Most recently, after reading Brian Bushart’s awesome blog post, I have started taking the numbers out as well! Instead of students thinking about how they’re going to solve the problem as they read, they are truly thinking about the situation itself. It’s been an amazing way to give every student entry into a problem and allow me to differentiate for all of the learners in the classroom, while at the same time provide insight into my students’ mathematical understandings.

Recently, I had the opportunity to work with a 3rd grade class. The class recently finished their multiplication and division unit and will soon be starting their work with fractions. In order for their teacher and I to see and hear how students apply the operations, make sense of contexts, and currently think about fractions, I thought it would be interesting to take a story problem from their Student Activity Book and take the question and numbers out.

The Planning

I chose the problem below and thought about what I would learn about a student’s mathematical understandings and sense-making after they answered the questions.

I was curious to observe how students make sense of problems based on the idea of removing the numbers and the question so I changed the problem to this simple statement:

“Webster has boxes of granola bars to share with his class.”

I anticipated the students would wonder about the missing mathematical pieces involved in an open-ended statement like this. I believed their wonderings could lead them to develop questions that could be answered based on the very information they were wondering about. I knew the mathematical ideas of multiplication, division, and/or fractional sharing would arise and that I would learn so much more about their thinking then if I had given them the original problem.

In The Classroom:

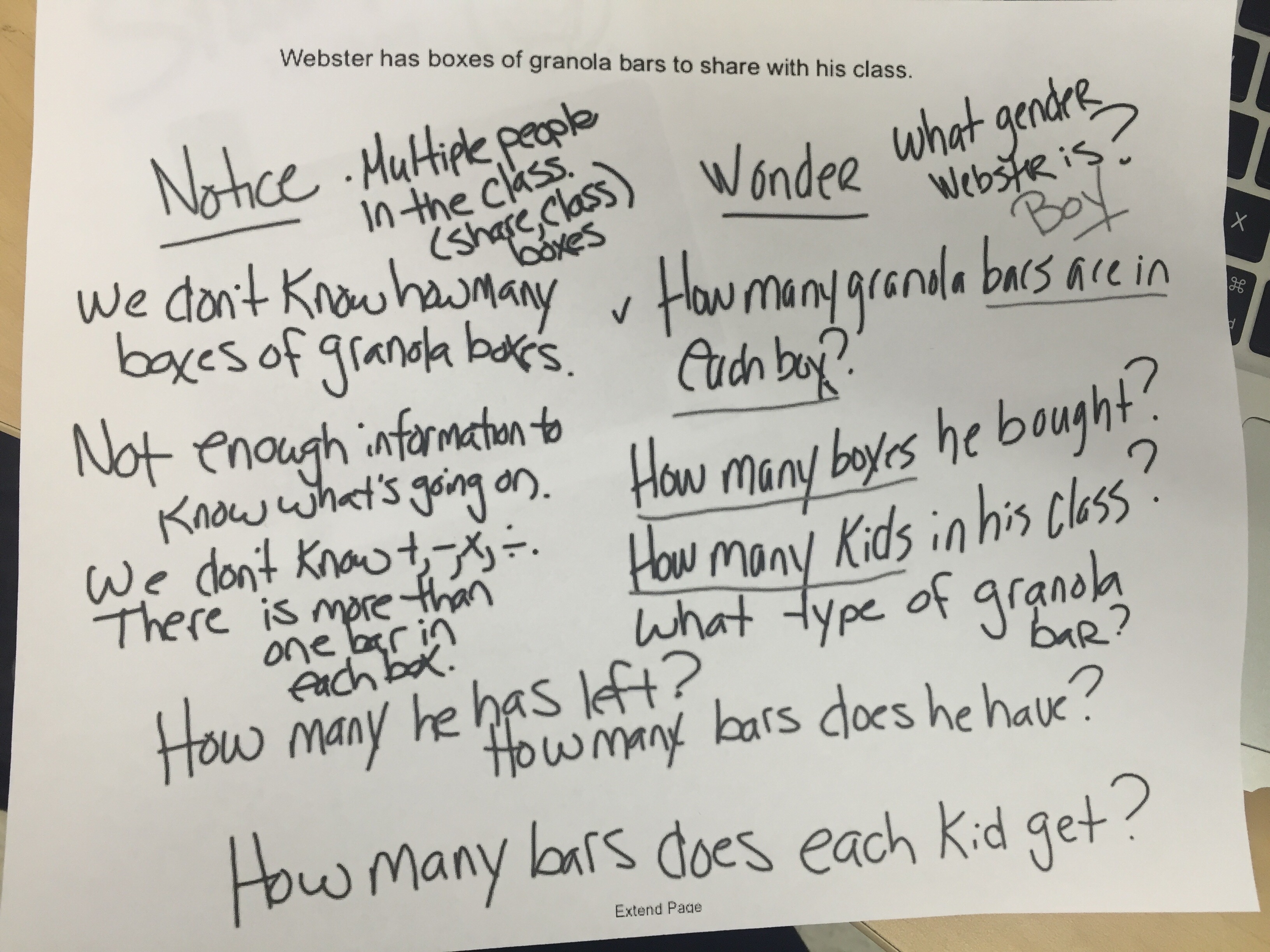

I launched the lesson by posting the sentence on the board and recorded things they noticed and wondered.

They noticed:

“We don’t know how many boxes of granola bars.”

“There is not enough information to know what is going on.”

“We don’t know if it is adding, subtracting, multiplying, or dividing.”

“There are multiple people in the class because it says boxes and share.”

They wondered:

“How many granola bars are in each box?”

“How many boxes he bought?”

“How many kids are in his class?”

“What kind of granola bars are they?”

Based on their noticings and wonderings, I felt everyone had a strong grasp of the context and sense of where this was going. Based on their noticing that there is not enough information to know what is going on, I asked what more they would want to know. They responded that they wanted the answers to the first three of their wonders: bars per box, number of boxes, and number of kids in the class.

I asked them what questions they could answer if I gave them those pieces of information and they responded:

How many bars does he have?

How many bars does each kid get?

How many does he have left?

At this point, I could have given them the information they wanted. However, I thought it would be so much cooler to allow them to choose that information for themselves. I was curious: how they would go about choosing their numbers! Would they strategize about the numbers to make it easier for themselves? Would they even think that far ahead? What would they do with the leftovers?

When I told them I was not giving them the information and that instead they were choosing their own numbers along with the question they wanted to answer, they were so excited!

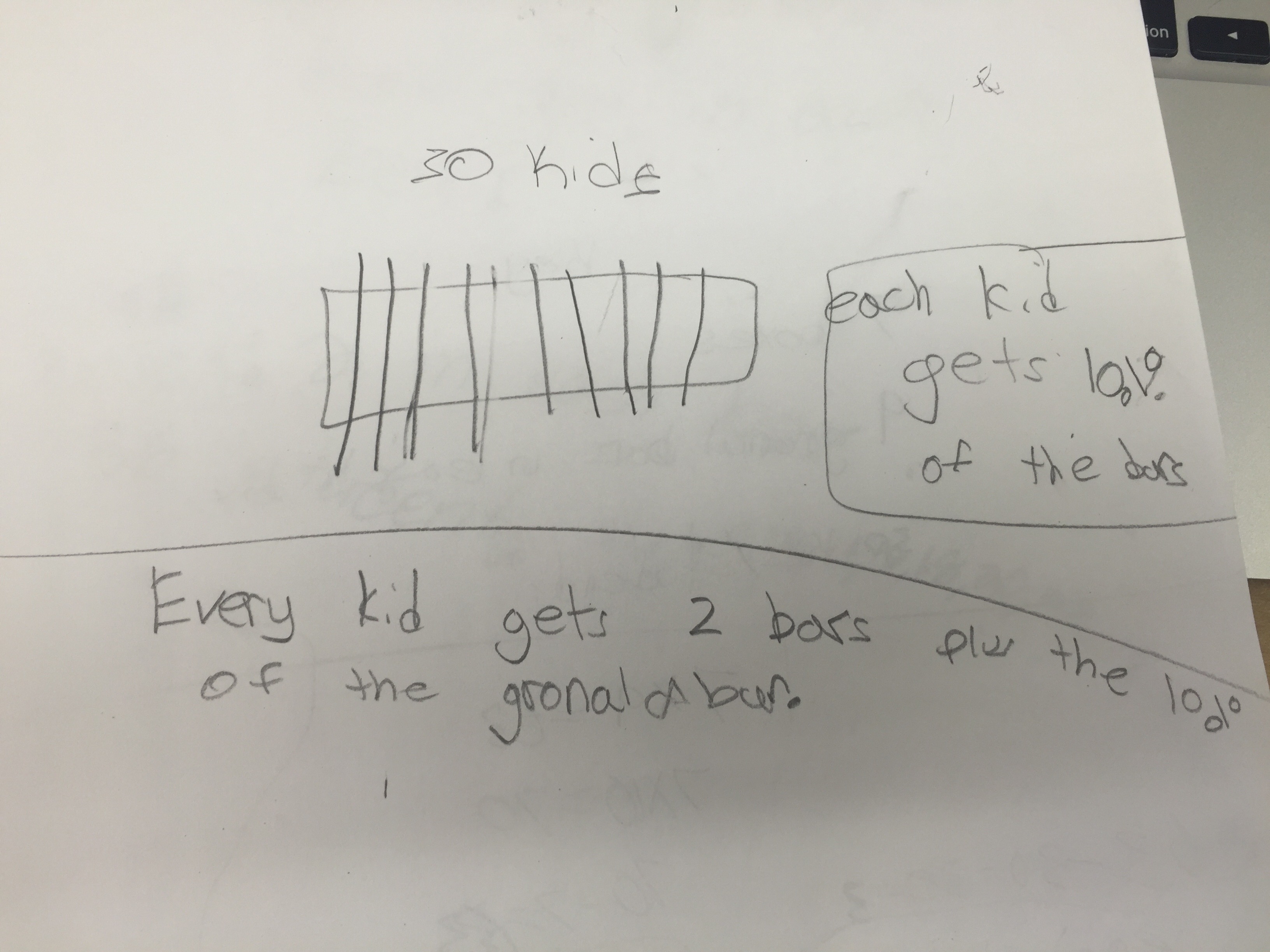

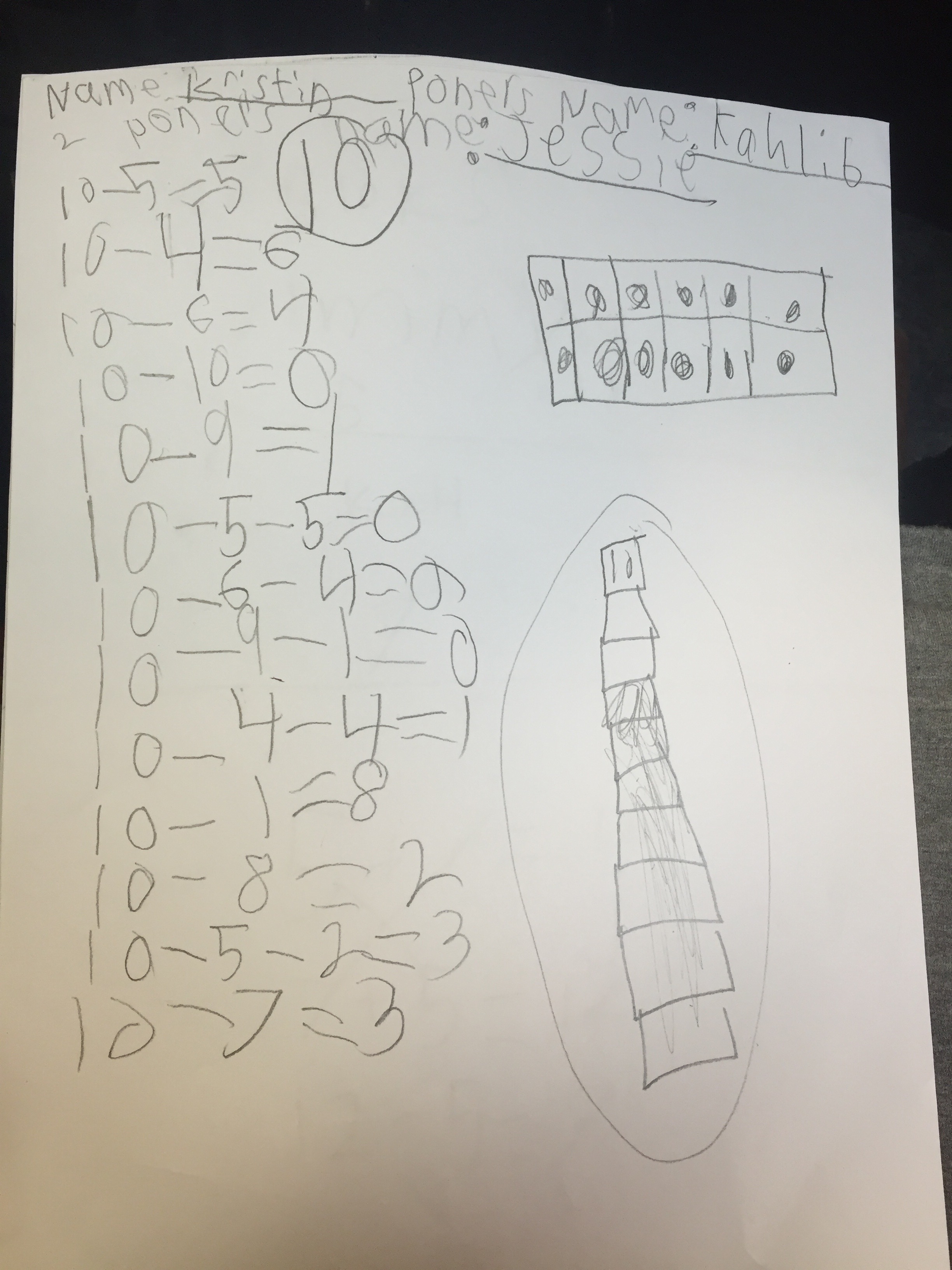

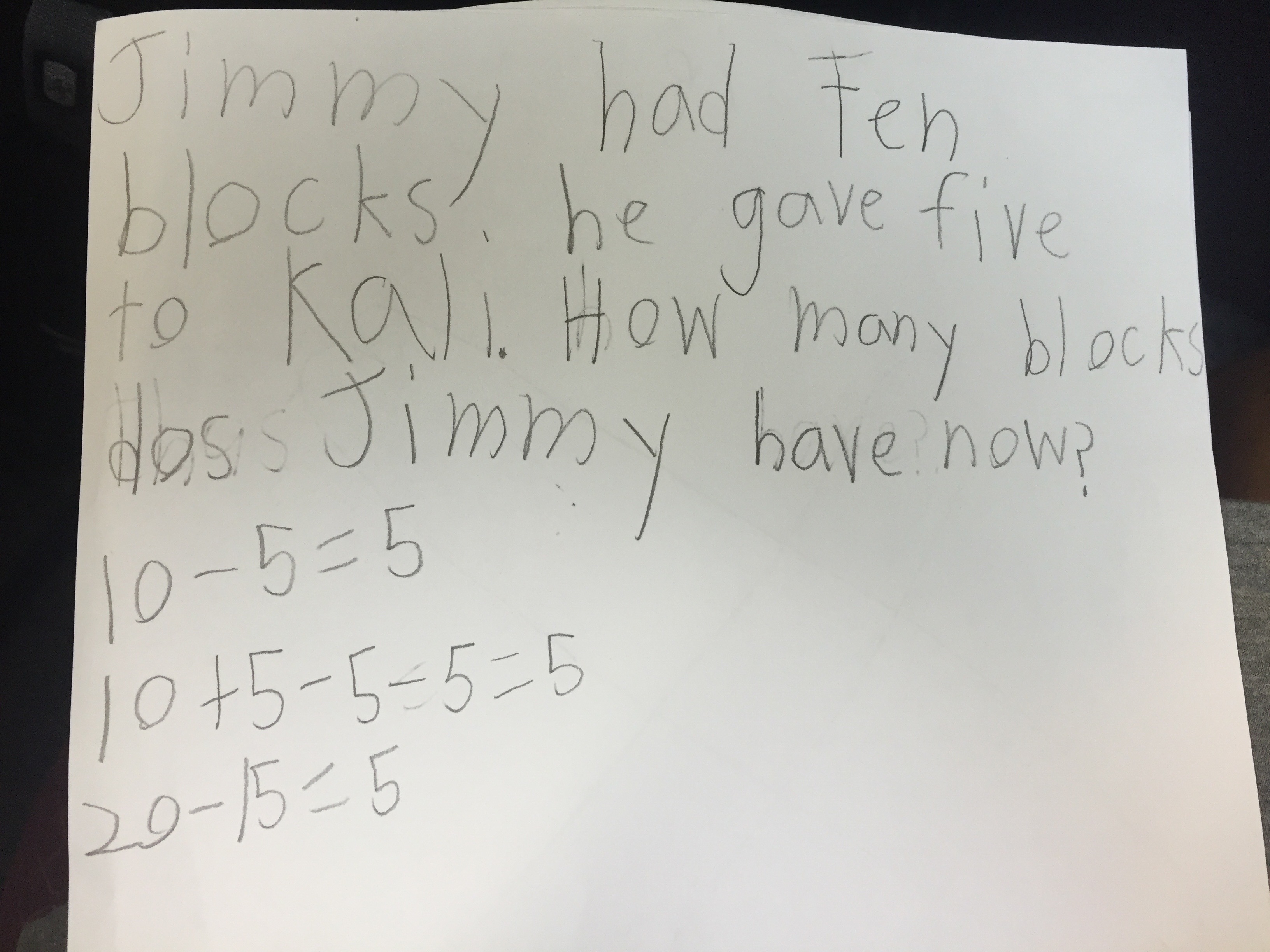

Some partners chose their numbers very strategically to make it easier for themselves. To me, this demonstrated a lot of sense-making and forethought of what was going to happen in their solution path. And as an added bonus, while only asked to answer one question, the group answered all three questions! (Teacher note: if students chose numbers strategically and therefore finished quickly, I gave them extra bars to factor into their problem to see how they dealt with the leftovers.)

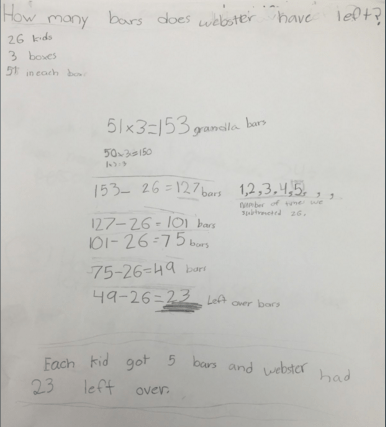

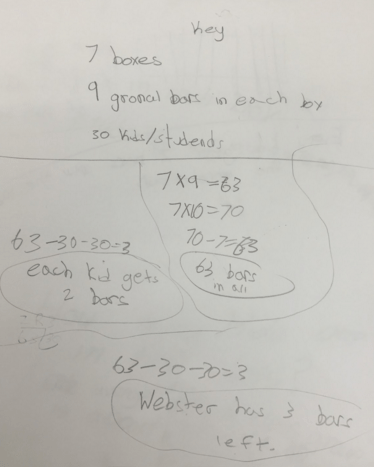

Other students chose the opposite route and strategically picked numbers to make it “harder for themselves.” Check out the way these two students showed strong reasoning and perseverance through division of numbers larger than any they’ve ever worked with.

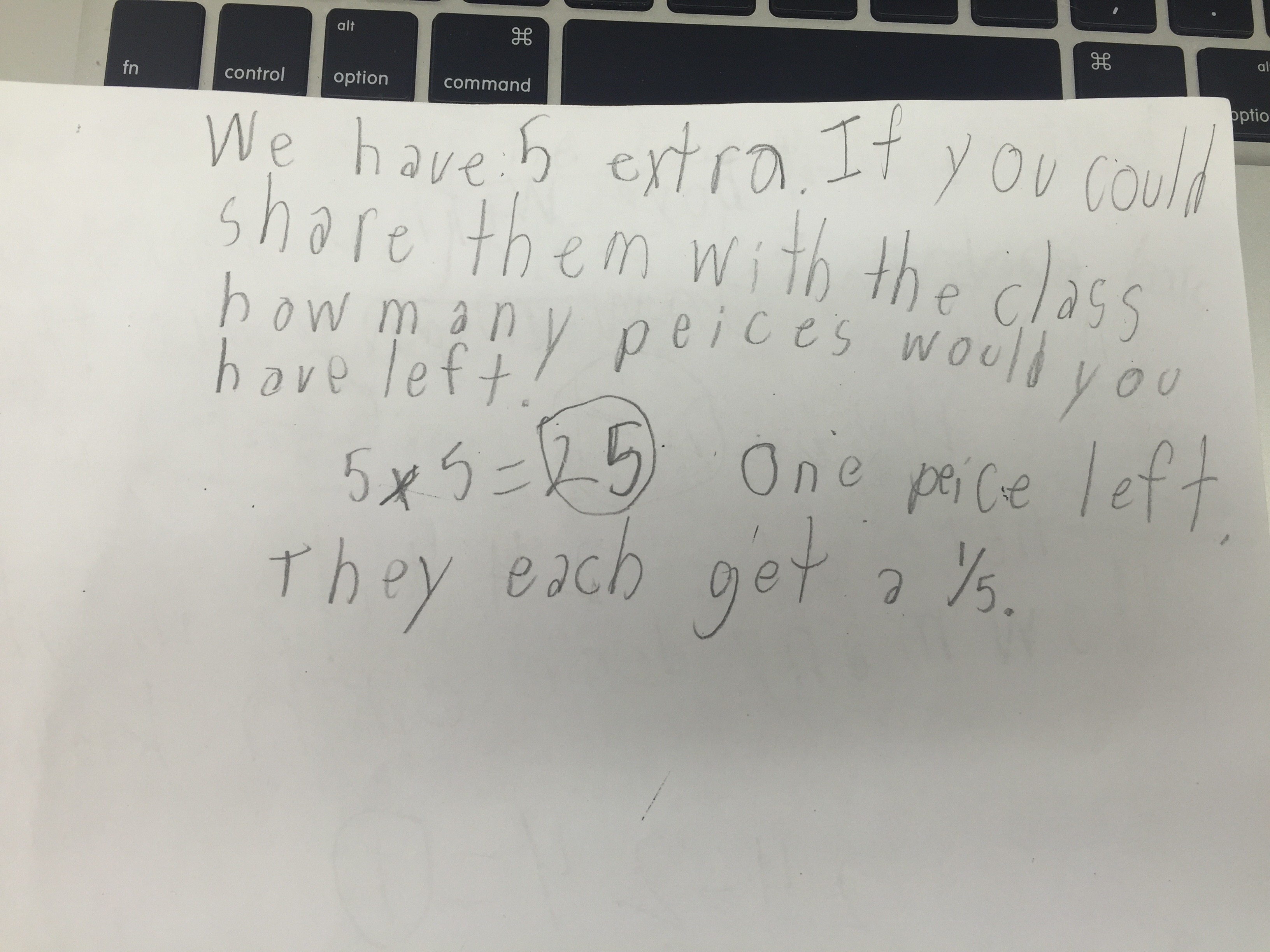

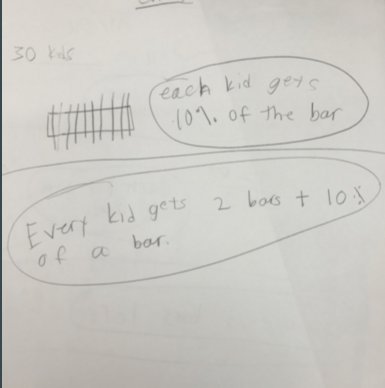

Others chose numbers without much forethought and dealt with some amazing leftovers. This was a great way to formatively assess students’ thinking related to fractions before they began that unit.

And then there are always the surprises. Who would have thought third graders would reason about the leftovers in terms of percentages?

Reflecting on what the students would have been asked to make sense of and the work they would have had to do based on the original problem versus the reasoning and work they did related to this one simple sentence, I’m amazed by the difference. I learned so much more about what each of the students know beyond simply multiplying 5 and 6. Taking out the numbers and question allowed every student to think about the meaning of the sentence, the implied mathematical connections, and plan a solution pathway before jumping into a solution attempt.

I highly recommend everyone try this strategy with a word problem from your current text. It’s a wonderful way to give every student access to the math and freedom to think beyond just getting an answer.

If you know me or have ever read my blog, you know I could talk for days about student math work! You can visit my blog for a more detailed description of the work shown in this post as well as additional work captured from the lesson.