In our 2-D geometry unit, we have been classifying polygons based on attributes of sides and angles. This week, the students were using what they know about angle measures and polygons to find the measures of other angles. These are the polygons students were working with:

The first day, I put polygon F on the whiteboard and asked tables to develop a proof for the angles in F. I was excited to see they had worked with this in 4th grade and were comfortable in being able to prove it was 90, 45, 45. Here are a couple of the proofs from that day’s work…

It was interesting to my colleague and I to really think deeply about what the students were saying in their explanation. We had to ask ourselves if they were really thinking about the angle itself when they were saying “A triangle is 180º because it is half of a square which is 360º.” Their proof with the polygons looked like an area model, so were they thinking about the angles or thinking that the area of the triangle is 180?

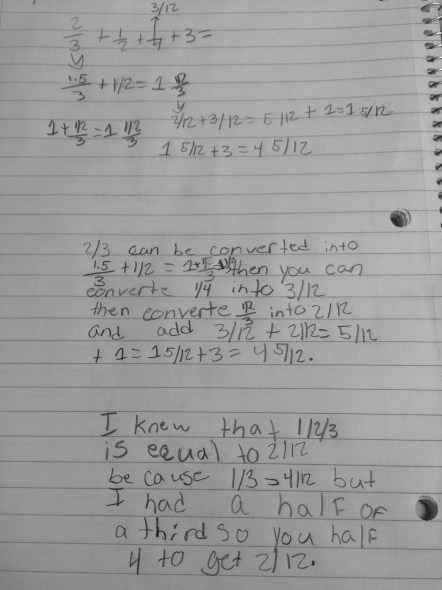

In the next activity, I really wanted to focus on students composing and decomposing the angles themselves. They worked in groups to find the angle measures of the remaining polygons on the above sheet. Here are a few of their proofs that we shared as a class.

After sharing our proofs today, I felt very comfortable with student understanding of finding missing angles and thought it would be interesting to move into construction of these shapes in Hopscotch (a coding app). This is one of those things that is not explicitly in the curriculum, but something I just think is so great for students to explore. It is wonderful for students to see angles as turns and explore supplementary, interior and exterior angles.

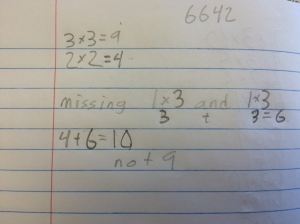

We practiced making a square together to be sure everyone had an understanding of how the codes worked and then I sent them off to build the triangles. You can imagine the surprise as they punched in 60º for the turn to make an equilateral triangle and the character shot off in the wrong direction. I let them work their way through it and then reflect in their journals after. Here are some of their thoughts…

They left me with so much to think about for Monday’s lesson. I love the idea of a negative number makes them turn the other direction, the relationships to 180º, and the two angles adding up to 180º. Interesting stuff!

-Kristin