I’ve always had such an appreciation for curriculum materials. I genuinely don’t know where I would have been as a new teacher without the Investigations curriculum. Those materials shaped my vision for math instruction and influenced not only my teaching, but my curriculum writing at Illustrative Mathematics as well. In all of my work, I continually advocate for the use of high-quality instructional materials.

At the same time, I’m not naïve enough to believe that any single curriculum—no matter how well designed—can meet the needs of every teacher or every group of students in any context. That tension is exactly why I care so deeply about adaptation.

For some curriculum publishers ‘adaptation‘ is treated as a dangerous word because it doesn’t align with the curriculum developers beliefs about how their curriculum should be used. Some worry that acknowledging the need for flexibility somehow sends the “wrong message” about the quality of the product.

What those organizations need to honor is what teachers know: their students, their prior knowledge, the ways they engage with content, and the day-to-day realities of a classroom. Pretending a curriculum is so perfect that it must be used exactly as written may keep a marketing narrative tidy, but it doesn’t support the humans doing the teaching, or the kids doing the learning.

Adaptations: The What and Why

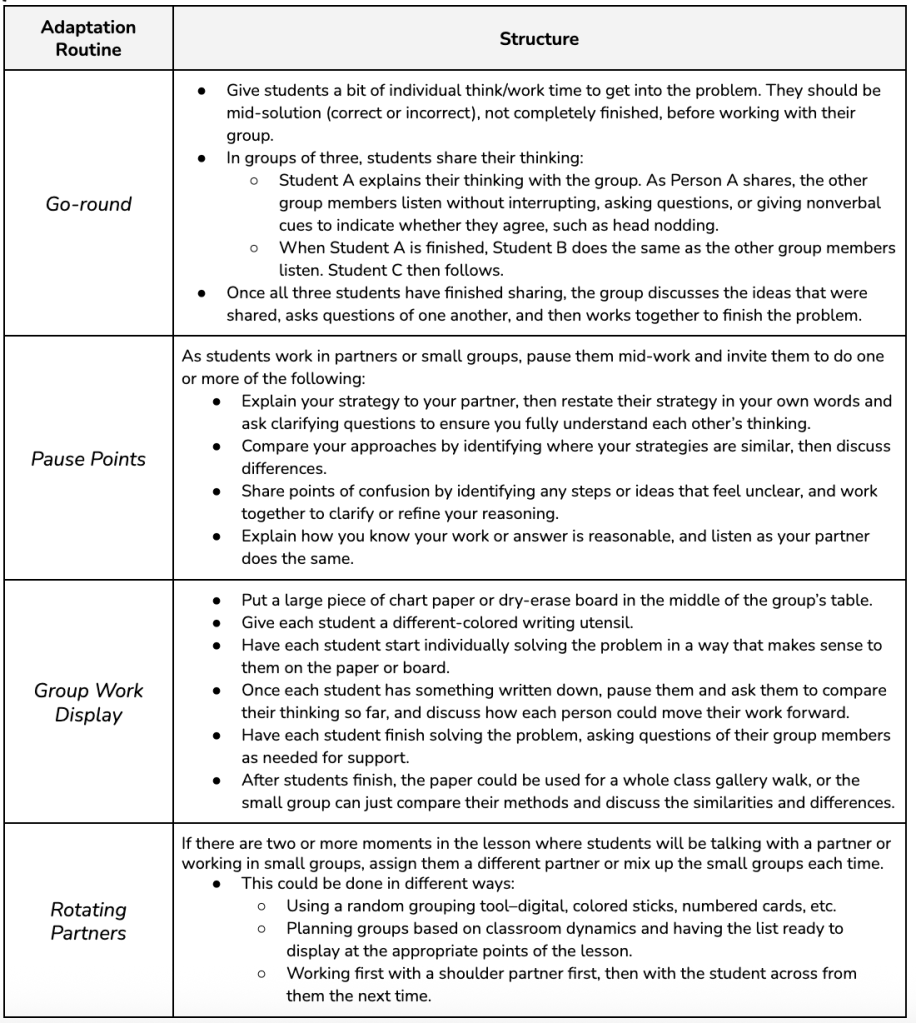

Sometimes adaptation means shifting pedagogy.

Sometimes it means bringing in a strategically chosen resource.

Sometimes it means adjusting a task to better elicit the mathematical ideas at the heart of the lesson.

At its best, adaptation is about eliciting, honoring, and leveraging students’ ideas, curiosities, strengths, and mathematical understandings. It’s about making intentional choices that build from what students can do rather than from assumptions about what they can’t or won’t.

But over the years, I’ve noticed a pattern that feels impossible to ignore: instead of investing in thoughtful adaptation, math education has become (or always has been?) obsessed with quick fixes and flashy things.

We try them. We buy them. We’re promised they’ll solve our most persistent instructional challenges.

You’ve probably heard versions of this:

- Students are ‘falling behind’ in grade level content → Purchase an RTI program.

- Students aren’t being challenged → Create an accelerated track.

- Students aren’t engaged → Make flashy digital lessons.

- Students still aren’t engaged → Find “fun” activities on the internet.

- Students aren’t writing explanations → Buy math journals.

- Teachers don’t believe all students can learn → Hand them a book on growth mindset.

- Teachers still don’t believe all students can learn → Hire a ‘big-name’ math ed keynoter.

- Teachers can’t meet every student’s needs → Send them research on differentiation.

- Teachers don’t trust their curriculum → Replace it with a collection of random tasks.

- Districts don’t trust any curriculum → Throw out the textbook altogether.

These moves usually come from care and urgency. When something isn’t working, it’s natural to want to fix it and in many cases, we can learn a lot from trying new things. I know I have learned a ton from the #mtbos days of old.

But these are not challenges for quick fixes. They are ‘easier said than done’ pain points. So, it’s worth pausing to ask: If these solutions are meant to produce consistent, measurable, and sustainable change…why are we still looking for solutions for the same problem?

The answer might lie in how we think about mathematics itself.

Math Is a Story. Quick Fixes Are Commercials.

When we see mathematics as a coherent story, one that builds, connects, and makes sense over time, each lesson is a chapter. New ideas grow out of previous ones. Students should feel the mathematics unfolding, connecting, and extending their thinking.

That story is already written into high-quality curriculum materials. Our role as teachers is to bring it to life, making adaptations that strengthen the narrative without breaking it.

Quick fixes, however, often come with their own storyline: their own logic, pacing, and purpose. When we drop them into instruction without careful consideration, they interrupt the mathematical story already in progress.

They become commercials.

And even when the commercial is fun, flashy, or well-intentioned, it still disrupts coherence and the learning experience. It’s unlikely, certainly not guaranteed to lead to lasting changes in teacher practice or student learning.

When teaching and learning are treated as a continuous, interconnected narrative, commercial breaks can add noise, not clarity. They leave students experiencing math as a series of disconnected activities rather than as a meaningful, connected discipline.

Thoughtful adaptation preserves the story. Quick fixes interrupt it. I even gave a talk on this exact idea at CMC-S many years ago. (minute 9:00)

The Things Aren’t the Problem , Our Lens Is

Once you start seeing instruction this way, it becomes easier to spot where coherence is preserved and where it gets disrupted. One of the clearest examples of this tension shows up in how we use math routines.

There is no shortage of powerful routines in math classrooms:

- Number Talks

- Which One Doesn’t Belong

- Notice/Wonder

- 3-Act Tasks

- Visual Patterns

- Counting Collections

- Choral Counting

- Sometimes/Always/Never

- Talking Points

- Open Middle

I LOVE these routines. I’ve used them in my own teaching, coaching, and curriculum writing because I deeply understand their value. Each one holds enormous potential and I have learned so much by using them. They invite reasoning, elevate student voice, and cultivate important mathematical habits of mind.

But their impact doesn’t come from the routine itself—the thing.

It comes from the things about the thing:

- its mathematical purpose

- how it positions students as thinkers

- the teacher’s stance and what they notice and respond to

- how it connects to what came before

- how it advances what comes next

- the opportunities it creates for sense-making

When a strong routine, activity, or other pain point solution is dropped in at random, it becomes just another commercial, well-produced and engaging, but disconnected from the larger story of the mathematics.

When that same routine (or other solution) is used with intention, grounded in the curriculum and responsive to students, it becomes part of the narrative and an agent for sustainable change.

How to Shift Our Lens

Shifting our lens doesn’t mean rejecting new ideas, routines, or resources. In fact, it requires the opposite. We try things. We study them. We learn from what happens when they meet real students in real classrooms. But instead of treating those things as replacements or fixes, we treat them as opportunities to better understand our students and the mathematics, and then adapt with intention.

This is where adaptation becomes the missing piece in effective and sustainable math instruction. Without adaptation, we swing between rigid fidelity (“just follow the program”) and disconnected add-ons (“just try this new thing”). Adaptation offers a third path: staying grounded in the curriculum’s design while making informed, purposeful decisions that support coherence and respond to students’ thinking. It asks not What can I insert? but How does this choice strengthen the mathematical story students are already experiencing?

Importantly, adaptation is not a free-for-all. As Remillard (2005) reminds us, “It would be inaccurate and irresponsible to conclude that all interpretations of a written curriculum are equally valid.” Some changes preserve the integrity of the mathematics; others unintentionally distort or fragment it. The work, then, is not simply to adapt but to learn how to distinguish between reasonable and unreasonable variations, especially those tied to the most central features of a curriculum’s design (pp. 239–240).

When we shift our lens in this way, trying something new is no longer the end goal, it’s part of a learning cycle. We try a routine, task, or approach. We notice how students engage with the mathematics. We reflect on what it revealed, what it obscured, and how it connected to what came before and what comes next. Then we adapt, not to chase novelty or flashy, fun options, but to better position students as sense-makers within a coherent mathematical storyline.

This kind of adaptation doesn’t promise instant results. But it does something far more powerful: it builds teacher knowledge, strengthens instructional decision-making, and supports math learning that is connected, meaningful, and sustainable over time.

So Where Do We Go From Here?

We don’t need to jump to new things to solve curriculum implementation challenges.

And we certainly don’t need more silver bullets.

What we need is coherence.

We need connectedness.

We need to treat mathematics as the coherent story it truly is and learn to adapt materials in ways that honor and strengthen that story.

That also means being more intentional about the curriculum partners we choose. We should be asking whether a curriculum acknowledges the professional judgment of teachers, reflects the complexity of classrooms, and explicitly supports thoughtful adaptation. The goal is not permission to change things at will, but guidance for how to adapt in ways that preserve the mathematical integrity and coherence of the design. Organizations that condemn teachers for adaptation, or frames it as a failure of implementation, misses a fundamental truth: no written curriculum can anticipate every learner, every context, or every instructional moment.

Choosing adaptations, then, requires looking beyond the thing itself and toward the things about the thing that make instruction sustainable, purposeful, and responsive to teachers and students. One way to begin is by grounding adaptations in a small set of guiding questions and principles.

First, adapt with the mathematical purpose in mind.

Before changing a task, routine, or lesson, be clear about the mathematics it is designed to surface. Strong adaptations clarify or sharpen that purpose; weaker ones obscure it. Sometimes that sharpening means being more explicit, naming an idea directly, modeling a strategy, or slowing down to highlight structure so students can actually see the mathematics you want them to see. If an adaptation makes the mathematics less visible, dilutes the focus, or shifts attention away from key ideas, it’s worth reconsidering.

Second, protect the coherence of the learning.

Ask yourself how the adaptation connects to what students have already experienced and how it sets them up for what comes next. Reasonable adaptations strengthen the storyline, helping ideas build, connect, and deepen over time. When an adaptation stands alone or introduces a competing logic, it risks becoming a commercial rather than a chapter.

Third, attend to how students are positioned.

Effective adaptations expand access to the mathematics without lowering the cognitive demand. They position students as thinkers, sense-makers, and contributors, not just followers of procedures. The question is not Is this easier or harder? but What opportunities does this create for students to reason?

Fourth, treat adaptation as learning, not fixing.

Adaptations work best when they are tried, studied, and revised. What did students understand more deeply? What surprised us? What might we adjust next time? This stance shifts adaptation from a reactive move to an ongoing professional practice.

When we adapt with these elements in mind, every instructional choice becomes part of a larger narrative: what students understand, who they are becoming as mathematicians, and how they make sense of the world.

And when we stop interrupting the story with commercials, the learning becomes clearer and the thinking becomes deeper.

Now if we revisit our initial list and reflect on the things about the thing, we move from quick fixes to thoughtful considerations.

- Students are ‘falling behind’ in grade level content → How is the RTI program connected to our curriculum materials? How does the program position students as knowers and doers of mathematics? How does the program build on what students know?

- Students aren’t being challenged →What does it look like to extend student thinking? How does our current curriculum support extensions? How can we adapt our current curriculum materials and instruction to extend student thinking? How are teachers supported to address all students needs’ in the classroom?

- Students aren’t engaged →Why would a digital activity be more engaging? Why would the digital activity be better than a pencil/paper experience? How does it impact students collaboration? What is the cost/benefit of putting students on a device during math class?

- Students still aren’t engaged → How do the ‘fun’ activities connect to what students are currently learning? What aspects of that activity make it fun? Which of those aspects could be implemented in our current lessons to increase engagement? Does fun= meaningful learning?

- Students aren’t writing explanations → How do students view writing in math class? What do we do with their written explanations? How do I need to manage the journal to encourage students to write more?

- Teachers don’t believe all students can learn → How can we find out why teachers believe this? How can we adapt our curriculum materials to elevate student ideas to show all of the amazing things students know?

- Teachers still don’t believe all students can learn → How can we collaborate as colleagues to learn more about how students feel about themselves as mathematicians? How can we leverage what we learn to adapt our instruction to elevate all of the knowledge students are building on.

- Teachers can’t meet every student’s needs → What does it mean to differentiate? What are in the moment strategies we can use? How can we make the most out of any small group time we have? How can we leverage collaboration in the classroom to support differentiation?

- Teachers don’t trust their curriculum → How can we find out why teachers don’t trust the curriculum? How can support teachers in adapting the curriculum in meaningful ways to gain trust?

- Districts don’t trust any curriculum → What are the implications if we don’t have a scope and sequence? How does just pulling tasks aligned to standards impact student’s learning experience?

Final Thoughts

In the end, thoughtful adaptation is not about changing for the sake of change, it’s about honoring the complexity of teaching and the brilliance students bring to mathematics. High‑quality materials give us the storyline; our professional judgment brings that story to life. And that work becomes even stronger when it’s supported by curriculum partners who believe this too–partners who trust teachers, understand the realities of classrooms, and design materials that are meant to be adapted rather than protected with rigidity.When we adapt with purpose, protect coherence, and remain responsive to the learners in front of us, we create classrooms where mathematics makes sense, ideas build, and students see themselves reflected as capable thinkers. That’s the work that lasts. That’s the work that matters. And that’s the work worth investing in, not because it’s easy, but because our students deserve instruction rooted in meaning rather than momentum, in coherence rather than commercials, and in teaching that grows stronger, deeper, and more human over time.

Related posts on adapting: