I have always loved, loved, loved Jenna’s Slow Reveal Graphs! They provide such an engaging structure that encourages students to explore and reason about data. If you don’t know what Slow Reveal Graphs are, it might be helpful to read up on them here before continuing.

Sense-making is so front and center in a slow reveal activity that I think it could be interesting and exciting to extend this activity with problem posing! I have been learned so much about problem posing from my friend Jinfa Cai. Problem posing is an instructional approach in which students generate and solve their own mathematical problems. In doing so, students share mathematical authority in the classroom and position students as creators of mathematical inquiry rather than solely recipients. I wrote a bit about it in the new NCTM book, Teaching Mathematics Through Problem Solving (pg 73-74).

The Mashup

To think about what a mashup could look like, let’s go check out one of Jenna’s recent slow reveal graphs, Average Song Length by Genre. Which is so appropriate because Jenna and I love to chat 90’s hip hop artists;) Oh, and did I mention that Jenna creates a slide deck with notes for each one of these?!?

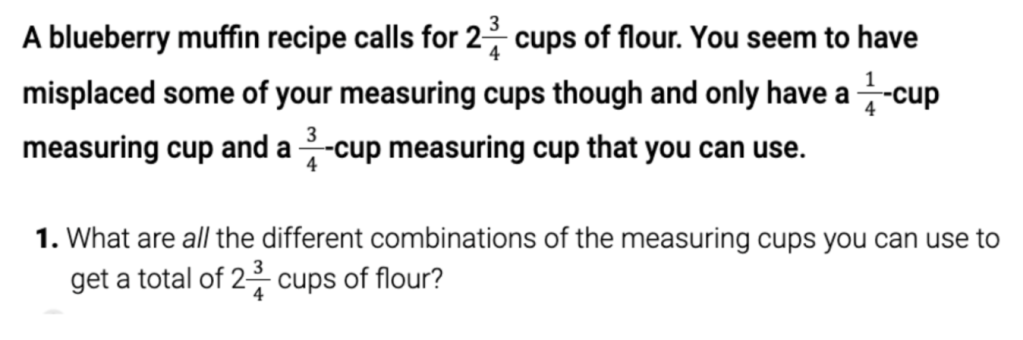

Step 1: Display the graph and ask students what they notice and wonder. (Slide 1)

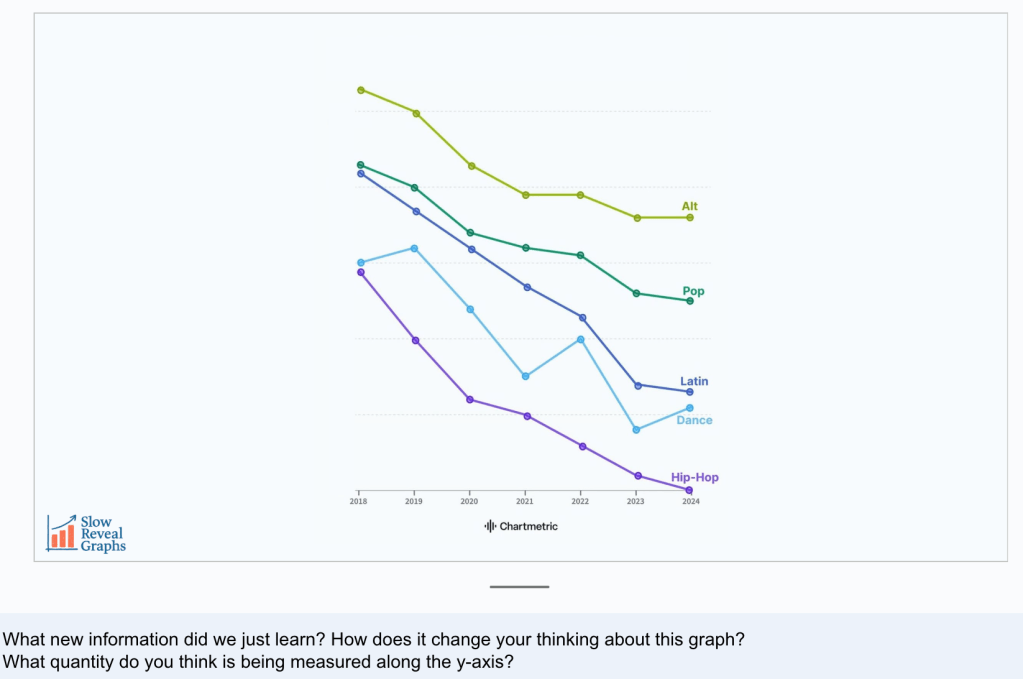

Step 2: Display the graph with new information, ask questions that encourage students to interpret the new information, and make predictions about what is still missing…luckily, these directions are in the slide notes of Jenna’s slides. (Slides 2-3)

Step 3: Display the final reveal of the graph. (Slide 4)

Step 4: Problem posing: Ask students to pose problems that can be answered by information in the graph and record them on a piece of chart paper.

Students might pose many different types of problems such as:

- Which genre had the longest average song in 2019?

- About how much longer was the average latin song than hip-hop song in 2023?

- About how much did the average pop song duration decrease from 2019 to 2024?

- Which genre had an increase in average song duration? Between what years?

- If you listened to a dance song and alternative song in 2022, about how many seconds would you be listening? How many minutes?

This list could go on and on, but you get the point. I know it could be nerve-racking to use a graph like this because there are not definite values at every point, but I think that actually increases the reasoning element and could raise some cool points for argumentation!

Step 5: Ask students to solve their problems.

This is a choose your own adventure — you could ask students to solve all of the generated problems or you could focus attention on one or two problems aligned to that day’s learning goal. I always lean toward the latter so the activity isn’t just a one-off random activity, but instead connected to what they are learning. This also leaves me a bank of ‘if you get done early‘ problems, which was always one of the biggest differentiation challenges for me, and helps me focus the whole group discussion afterwards.

Step 6: Synthesize the learning.

This step is really dependent on the learning goal of the day. After solving, you could have students do a gallery walk to compare solutions and solution methods, representations, and reasoning. Or you could decide to have a whole group discussion based on the monitoring that you did as students worked.

I have always been such a fan of numberless word problems, notice/wonder, and the 3 Reads MLR. Problem-posing feels like it pulls the most purposeful parts of each of these routines into one. Layering problem posing on Jenna’s slow reveal structure puts such an fantastic focus on data while also supporting other areas of mathematical focus. It is also so adaptable by grade level, which makes it so flexible!

Final Problem Posing Thoughts

When students have the opportunity to pose their own mathematical problems based on a situation, they must make sense of the constraints and conditions from the given information to build connections between their existing understanding and a new understanding of related mathematical ideas (Cai, 2022). And when teachers have the opportunity to listen to connections students make, understand the math students see in situations, and make teaching decisions on how to elicit, share, and move forward with student thinking, it shares the mathematical authority in the classroom and leads to deeper, more powerful learning for all!

I have blogged a bit about problem-posing if you are interested in learning more: https://kgmathminds.com/2023/09/23/embedding-problem-posing-in-curriculum-materials/ and https://kgmathminds.com/2023/05/06/problem-posing-fun-in-fourth/.