As a math teacher and coach, I’ve always adapted curriculum materials. I am sure we all have—it’s part of knowing our students and wanting to provide them with access to the math in ways that make sense to them. And while we have the best of intentions, sometimes the choices we make can unintentionally take the math out of students’ hands, disconnect from what they already know, or even reflect assumptions and expectations we didn’t realize we were holding.

Adapting activities is challenging for many reasons: some decisions require extensive prep, others happen in the moment, and all of them must be balanced with the pressure to keep pace while still giving students the time and space to share the incredible ideas, experiences, and mathematical thinking they bring into the classroom. I also found it difficult at times to know exactly what to look or listen for mathematically, and I sometimes interpreted students’ responses through my own assumptions and expectations. While a high-quality curriculum can provide problems that elicit student thinking, the deeper work of examining what we notice, what we value, and how we interpret and leverage students’ ideas extends far beyond even the most comprehensive teacher guide.

While thoughtful planning ahead of time is ideal, we all know it isn’t always possible. Because so much can get in the way of planning and prep time, I think a lot about how to make quick, in-the-moment adaptations based on what students are saying and doing—and on what I still need to learn about their thinking. I often wonder: What if our adaptations did more than simply “fix” a lesson? What if they opened space for deeper student thinking, a stronger sense of community, and richer mathematical understanding?

These questions keep pushing me to look closely at the flow of a typical lesson and identify the moments where even small adaptations can make a big difference. I’ve found that there are five points in a lesson where a few quick, minor changes can have a big impact:

- Launching an activity

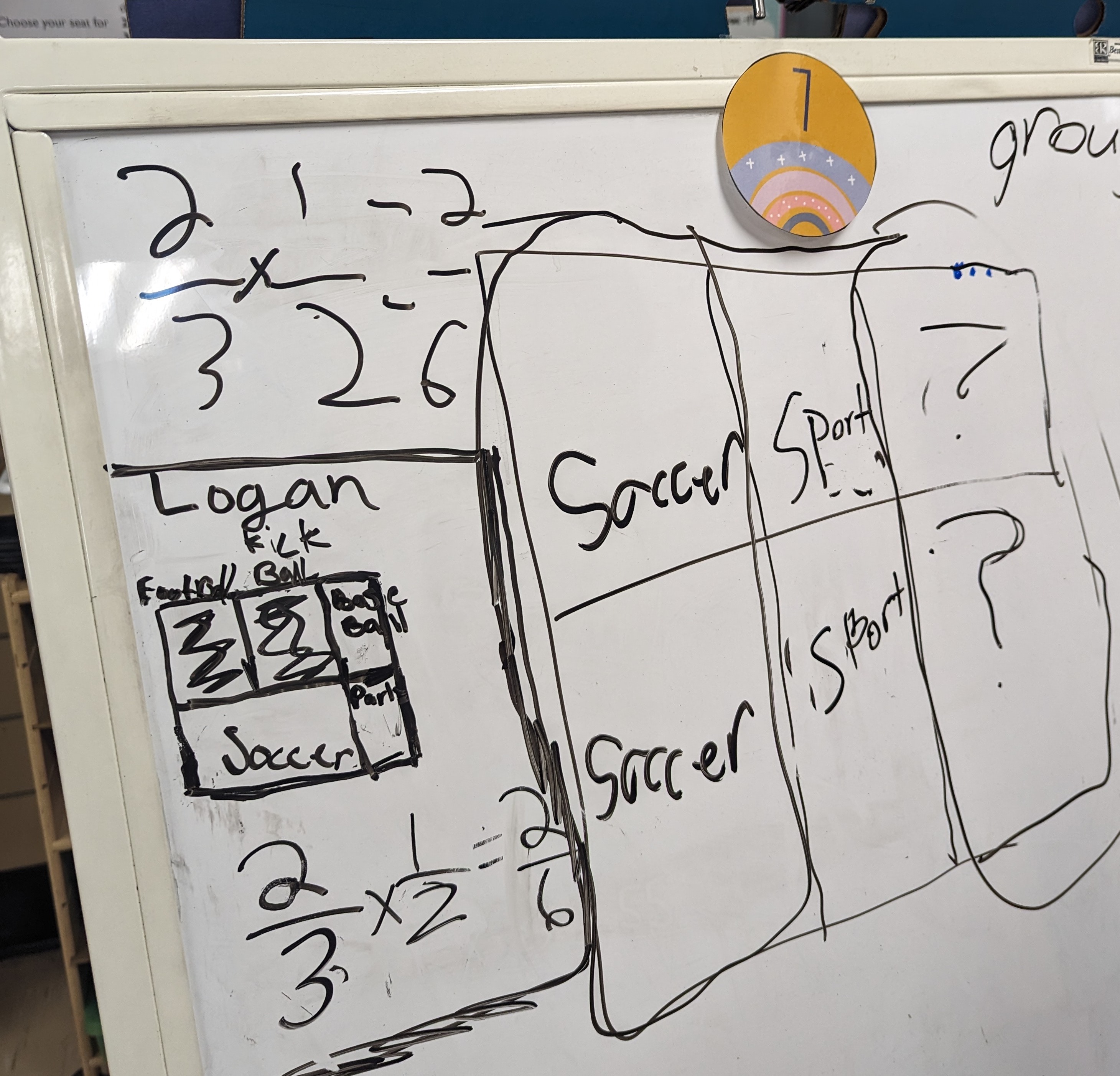

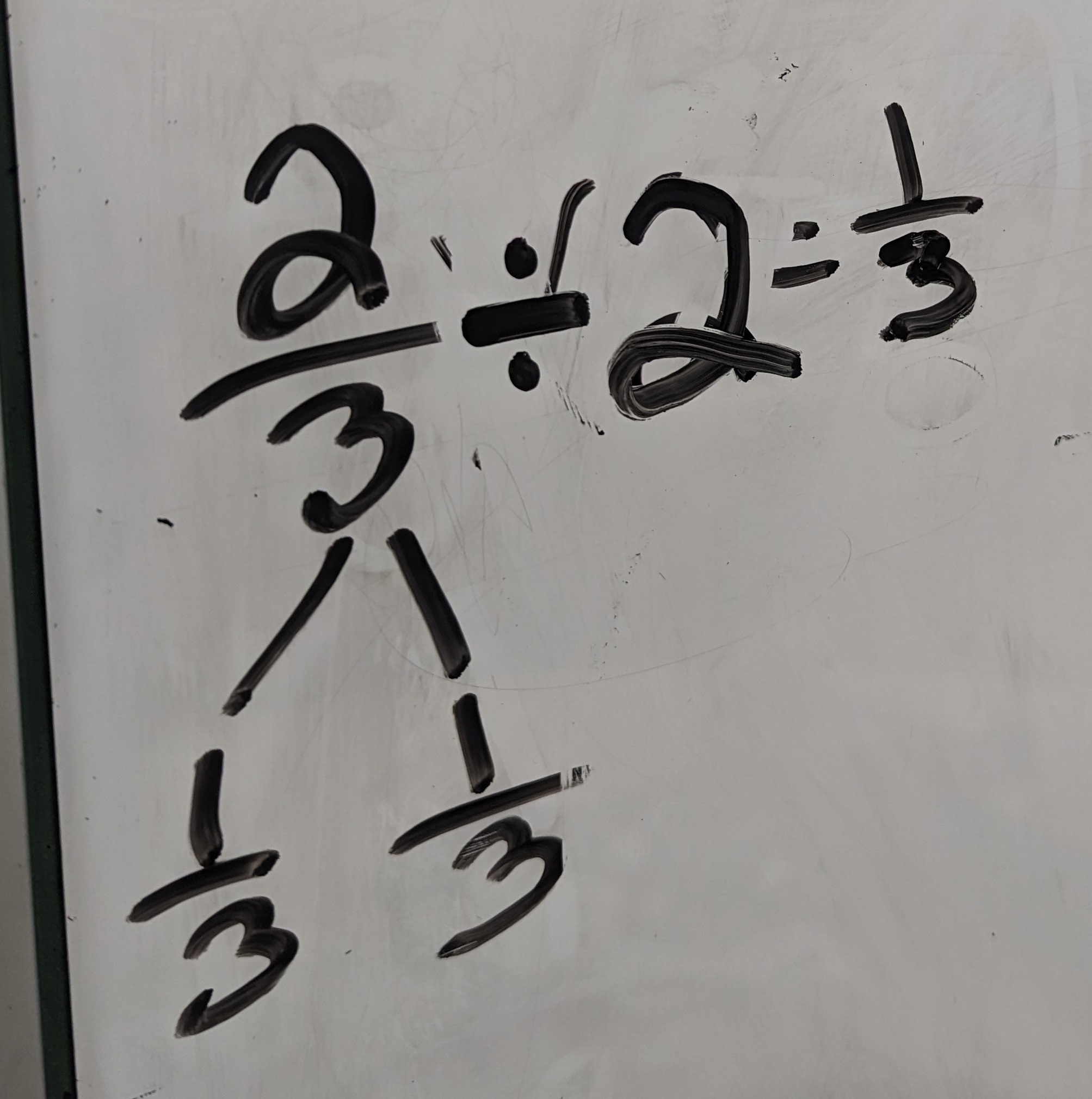

- Working in small groups

- Engaging with contexts

- Sharing ideas

- Synthesizing the lesson.

While it would be wonderful to have a single “right” adaptation for each of these, the reality is that different classrooms and moments call for different routines or structures. In the next series of posts, we’ll take a closer look at each of these opportunities and explore practical, in-the-moment ways to adapt them.

Ultimately, the goal of these small adaptations isn’t just to adjust an activity or lesson; they’re meant to open up richer mathematical experiences for students and provide increased insight for teachers. My hope is that these structures encourage sense-making and increase access to the mathematics; provide every student opportunities to share the amazing ideas they bring; create space for questions about one’s own or others’ thinking; build a stronger mathematical community; and support teachers in reflecting on why they’re adapting an activity and how those choices best serve students.

In this post, I’ll outline a few alternate ways to launch a lesson, and in subsequent posts, I’ll explore each of the other lesson moments listed above.

Alternate Ways to Launch a Lesson

Instructional Goal: Provide students with an entry point into the activity.

When deciding which adaptation to use, it is helpful to think about what aspect(s) of the task might make it inaccessible to your students. For example:

- If the context or representation of the problem might be unfamiliar to students, you could use the Tell a Story, What Questions, or Making Connections routine.

- If the activity relies on a prior knowledge from earlier in the year or prior grade levels, it might make sense to use the What Questions or Making Connections routine.

- If the language (including math language) adds a layer of complexity to the activity, you could use the Word Splash routine.

Try it!

There isn’t one “right” adaptation for any classroom scenario; each is an opportunity to learn more about your students. In the end, it’s not the routine itself that matters as much as what the routine affords—the ways it reveals student thinking, provides an entry point, and supports problem solving. The only way to figure out what works best is to try these structures out! Fortunately, they require little materials prep. All you need is a piece of chart paper or whiteboard and an image from the problem students will be solving.

In your next PLC or planning session, review the activities in an upcoming lesson. As you read through each problem, discuss:

- What knowledge and experiences are your students bringing to the problem?

- Is there an activity where students might not have access to the problem? If so, what specifically is inaccessible and why?

- Which of the four routines will you use to launch the activity?*

*If you’re planning with your grade-level team, each person can try a different routine and then compare the affordances of each one. I’d love to see what you try! Share your ideas in the comments or on IG (@kgraymath)!

Part 2: Supporting student learning as they work in small groups